On Friday, November 26, 1948, the day after Thanksgiving, known as the busiest shopping day of the year, Polaroid introduced the Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95, and Land Film, Type 40, to the public. Edwin Land stood at a precipice, wondering whether the significant investment and research in his new product would pay off. Land had wisely kept his costs down by operating in the low-rent industrial area of Kendall Square and, to his dismay, laying off hundreds of workers due to the post-war slump. "Everyone left at Polaroid knew that, at the present rate of decline, the business, the company, and their jobs might not survive 1947 or the first half of 1948," remembers Peter Wensberg.67

Ushering in the holiday sales season, the demonstration took place at Jordan Marsh in Boston, one of the region's leading department stores. To orchestrate the rollout of the product, Polaroid hired J. Harold Booth, known for his success in sales and marketing at Bell & Howell Company, a leading home movie manufacturer.68 Booth provided dealers with the "Polaroid Promotion Plan" that detailed the timing, logistics, and value of newspaper ads, training sessions, and demonstrations of the camera in order, Booth asserted, "to stage a dramatic introduction for a product destined to make photographic history."69

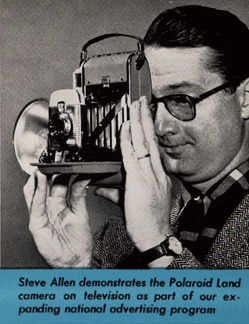

At $89.75, the leather-bound Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95, represented a high-end consumer purchase. All 56 cameras brought to the Jordan Marsh demonstration sold out. After its Boston debut, the Land Camera appeared at department stores in test markets in New York and Miami, a popular vacation destination. In order to establish greater connection with their customers, the company decided to distribute directly to dealers. Those selling Land Cameras quickly learned the benefits of a system that could take a photograph and instantaneously reveal the quality of the image. As sales manager R. C. Casselman sagely noted, "This is the first camera in history that can be completely demonstrated—and history shows that it's the demonstration that clinches the sale— providing it's a good one!"70 An early advertiser on television, Polaroid featured spots on the Dave Garroway Show in 1952 and the Steve Allen Show in 1954, where television hosts revealed through one new medium the wonders of another.71

At $89.75, the leather-bound Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95, represented a high-end consumer purchase. All 56 cameras brought to the Jordan Marsh demonstration sold out. After its Boston debut, the Land Camera appeared at department stores in test markets in New York and Miami, a popular vacation destination. In order to establish greater connection with their customers, the company decided to distribute directly to dealers. Those selling Land Cameras quickly learned the benefits of a system that could take a photograph and instantaneously reveal the quality of the image. As sales manager R. C. Casselman sagely noted, "This is the first camera in history that can be completely demonstrated—and history shows that it's the demonstration that clinches the sale— providing it's a good one!"70 An early advertiser on television, Polaroid featured spots on the Dave Garroway Show in 1952 and the Steve Allen Show in 1954, where television hosts revealed through one new medium the wonders of another.71

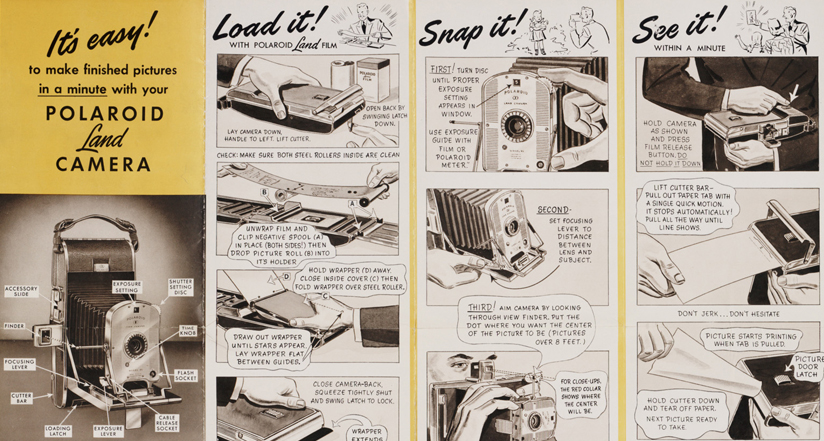

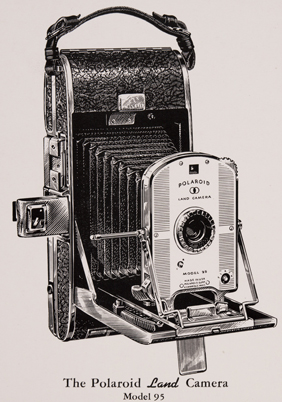

Polaroid excelled at customer service. Camera owners received letters of welcome and inviting instructional booklets illustrating the operation and features of the camera, with tips for good exposure, lighting, background, and composition. Walter Dorwin Teague, who also designed Polaroid's glare-free desk lamps, created a camera body made of die-cast aluminum with a satin-brushed chromium finish. The Model 95 weighed four pounds, two ounces, and measured 10 ½ by 4 ½ by 2 ½ inches. It featured a three-element 135 mm f/11 lens and shutter speeds from 1/8th to 1/60th of a second with an optical viewfinder that folded out.72 A single adjustment to the lens opening automatically set the shutter speed. In 1952, in addition to the Model 95, customers could choose the "Pathfinder" Model 110, a higher-end camera, and in 1954 the "Highlander" Model 80A, a smaller, more moderately priced camera.73

Polaroid instructional literature offered clear and precise illustrations that showed customers how to "drop load" the negative and positive spools into the camera, close the back, and pull out a leader of film until it stopped automatically. Taking the picture simply required extending the bellows, setting the shutter, focusing the lens, and pressing the exposure lever. After pushing the film-release button, customers pulled the tab out of the camera, and in a quick motion tore off the paper with the use of a built-in cutter-blade. After one minute, they unlatched the back of the camera to peel away a print that was face down toward the negative.74 The film packet, which retailed for $1.75, included eight exposures on the roll that produced 3 ¼- by 4 ¼-inch prints.75 A 100 ASA orthochromatic film, Polaroid Type 40 delivered sepia-toned prints. The semi-gloss images had white borders and deckled edges created from the die-cut perforations in the positive sheet. Polaroid gave customers the option of sending their prints back to the company in order to receive additional copies, enlargements, or negatives of their prints.

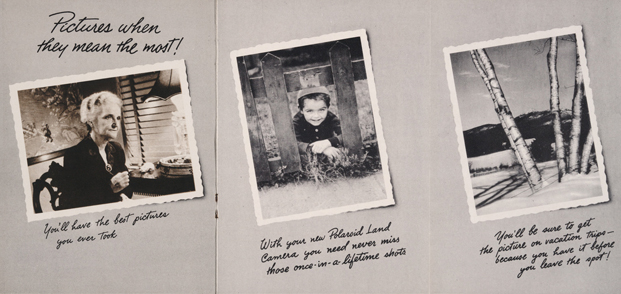

Polaroid advertising copy highlighted the wonder, ease, and instant rewards of a revolutionary system that "telescopes all the developing, fixing and stabilizing operations of ordinary photography into a single, one-minute step that occurs automatically when you advance the film for the next picture. . . . You can have your pictures when they mean the most. You can share and enjoy the pictures together with others in the pictures."76 Users also had the benefit of ascertaining on the spot if a photograph turned out to their liking and whether they needed to take another shot.

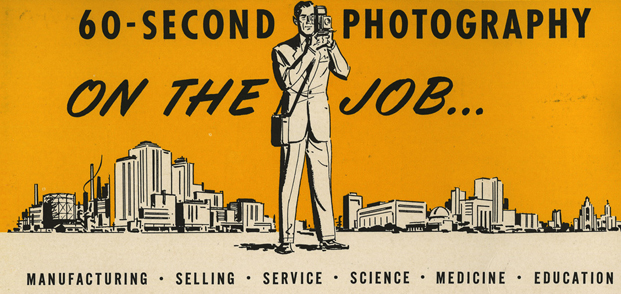

From the start, the company astutely understood and marketed wide-ranging uses of the camera. Promotional literature acquainted customers with the potential variety of instant photographs (family portraits, vacation scenes, shots of parties, weddings, birthdays, and anniversaries) as well as professional applications (in construction, insurance, real estate, journalism, personnel identification, medical instruction, and archaeology). In 1949, leading photography magazine U.S. Camera awarded Polaroid its U.S. Camera Achievement Award for outstanding technical achievement, noting how "photography has benefited from an application which places picture-making on an unparalleled level of popularity, and opens exciting new vistas for future development."77

- 66. Land, "One-Step Photography," 7.

- 67. Wensberg, Land's Polaroid, 90.

- 68. "Report to Stockholders," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1948, 4.

- 69. J. H. Booth, "How to Plan Your Polaroid Campaign . . . For Real Profits," "History—Early Camera" folder, Polaroid Corporation Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 70. R. C. Casselman, "Sales Autotype Letter no. 32H-1," November 30, 1955, Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.49, Folder 29, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 71. Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1952, 4; Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1954, 5.

- 72. "Facts about Operation and Construction of Polaroid Land Camera, Model 95," November 1948, 1 and 5, Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.314, Folder 3, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 73. "Report to Stockholders," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1952, 4; "Report to Stockholders," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1954, 3.

- 74. "It's easy! to make finished pictures in a minute with your Polaroid Land Camera" brochure, Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.243, Folder 6, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 75. "Picture-in-a-Minute Photography Emerges from Polaroid Laboratory," "History—Early Camera" folder, Polaroid Corporation Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 76. "A New Kind of Photography" in "It's easy! To make finished pictures in a minute with your Polaroid Land Camera" brochure, Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I. 243, Folder 5, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 77. Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1949, 2.