Polaroid advertisements featured the testimony of Polaroid users who claimed their cameras had made them "the life of the party."78 "The entire process of pose, exposure, anticipation, and response was shared by both the subject and the picture-taker," Peter Wensberg explains. "It was a new experience, a new pleasure."79 One-step photography inherently drew people together as they gathered around to see seemingly magical, instantaneous development of the print that took place before their eyes.

"The magic of image making is that the spectacularly thin layers—almost merely layers of concepts—evoke in the observers of the image the whole spread of human emotions," Land wrote. "It is hard to believe that such powerful responses are coming from such frail, delicate and inherently evanescent stimuli."80 Like earlier 19th-century photographic formats such as daguerreotypes and tintypes, "Polaroids"—as the revolutionary instant images were later called—emerged directly from the camera as positive, one-of-kind images whose thin, ephemeral layers nonetheless possessed a three-dimensional quality that invited users to hold and observe them. Author Peter Buse notes that just as leafing through a photographic album inspires an explanatory narrative, "by producing the print instantly in the very scene where it was taken, the Polaroid camera brings forward this familiar process, inviting or even demanding comment from those present."81

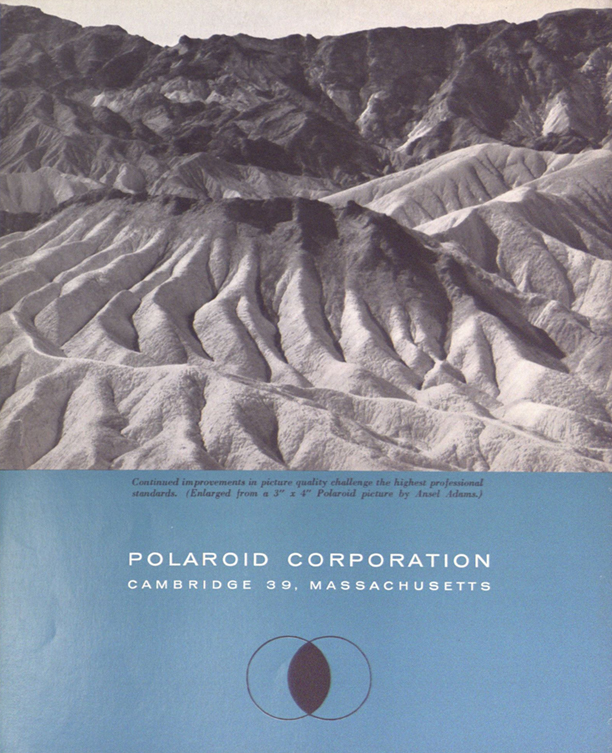

Edwin Land remained dedicated to the science and the art of creating a transformative photographic process that would capture the imagination of amateurs and earn the recognition of professionals. "The criticism leveled at the Land system was that it wasn't real photography, that it was an amateur's gadget and nothing more," Christopher Bonanos notes in Instant: The Story of Polaroid. "Land immediately took a big step to counter that idea, meeting an expert who in the coming years redefined what Polaroid photography could be. . . . the man Land met was Ansel Adams."82 Land hired Adams as a consultant to Polaroid in the late 1940s, beginning a collaboration that would last decades. A technical master known for the clarity and depth of his photographs, Adams in his early observations as consultant noted the limited tonal range of Type 40 sepia color film.

Polaroid introduced Type 41 black-and-white film in 1950, but the images, customers discovered, were prone to fading. As an interim step to address this product flaw, the company developed a film coater that users applied to black-and-white prints to keep them from fading. Meroë Marston Morse headed the black-and-white research lab in charge of creating a stable black-and-white print, which would prove to be years in the making. Nonetheless, the periodical U.S. Camera attested to the artistic potential of the new film: "The Land camera gives the photographer more of a chance to be an artist than any camera ever has before now. . . . This is especially true with the introduction of the new Type 41 (black-and-white) film which yields pictures-in-a-minute of exceptional tonal values."83 Adams's black-and-white Polaroid prints began to appear in the company's annual reports as well as photography periodicals like Aperture magazine.

Harold Livesay observes that in the way Henry Ford envisioned the Model T as an affordable means of transportation for all, so too did Land see his products as opening "vistas of art and communication for mass enjoyment."84 True to his humanistic nature and aesthetic sensibility, Land conceived of his revolutionary system as a democratic art form and means of expression. "An enormous number of people who lack talent or inclination for the early arts, do have the taste for and the need for a simplified medium of artistic expression," he reasoned.85 Test photographs by Polaroid employees from 1948 to the early 1950s, spanning the transition from sepia to black-and-white images, reveal the playful nature of the medium in everyday scenes as well as its artistic possibilities in portraits and still lifes with inventive compositions and remarkable tonal rendition. Instant photography put users in command of an art form in which they could create, compose, and share images instantaneously. "By making it possible for the photographer to observe his work and his subject matter simultaneously, and by removing most of the manipulative barriers between the photographer and the photograph," Land reflected, "it is hoped that many of the satisfactions of working in the early arts can be brought to a new group of photographers."86

- 78. Peter Buse, The Camera Does the Rest: How Polaroid Changed Photography (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2016), 110.

- 79. Wensberg, Land's Polaroid, 17.

- 80. Edwin H. Land, "Chairman's Letter," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1976, 5.

- 81. Buse, The Camera Does the Rest, 112.

- 82. Christopher Bonanos, Instant: The Story of Polaroid (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2012), 44.

- 83. "Polaroid-Land Process Now Has Black and White," U.S. Camera 13, no. 8 (August 1950): 42–43.

- 84. Livesay, American Made, 277.

- 85. Land, "One-Step Photography," 7.

- 86. Ibid.