In 1935, Edwin Land received the Hood Medal from the Royal Photographic Society, and in 1938, the Elliot Cresson Medal from the Franklin Institute in recognition of his pioneering work with polarizers. With the assistance of Richard Kriebel, Land presented the science behind his invention in a series of engaging public forums. In 1936, the young entrepreneur introduced his synthetic light polarizing discs at the Waldorf Astoria hotel in New York, an event covered by the New York Times, the Christian Science Monitor, and the New York Herald Tribune. H. I. Day of Electrical Research Products, Inc., impressed with the presentation, stated, "Land has solved a problem that every physicist working with light has struggled with for nearly a century."16 At the National Academy of Sciences in Washington, DC, in 1936, a demonstration of how polarizers work featured Wheelwright holding two discs of polarizing material and rotating them to the degree that a portion of his face no longer appeared. The converging discs, with their simple, delicate symmetry, became the trademark Polaroid logo—an elegant symbol for an enterprise dedicated to the intersection of science and art.

Public and professional recognition propelled the work of Land-Wheelwright Laboratories to the attention of Wall Street. In 1937, with major investments from James P. Warburg, a banker and financial advisor to President Franklin Roosevelt; Averell Harriman, a banker whose interests included the Union Pacific and Southern Pacific Railroads; J. P. Morgan, a banker and financier; and the investment banks Kuhn, Loeb & Company and Schroder, Rockefeller & Company, Land-Wheelwright Laboratories became reincorporated as the Polaroid Corporation. All existing and pending patents were transferred to the new corporation.17 Wheelwright left the company in the early 1940s, but stayed on as a member of the Board of Directors until 1948.

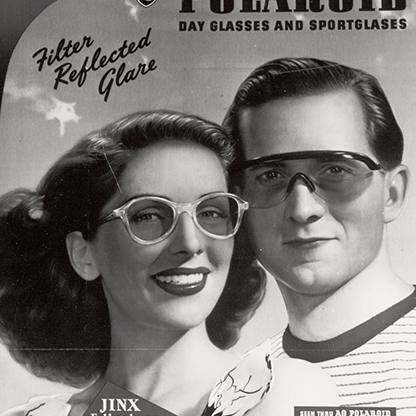

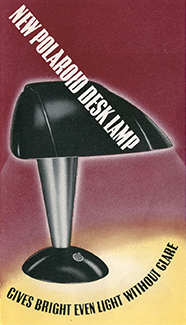

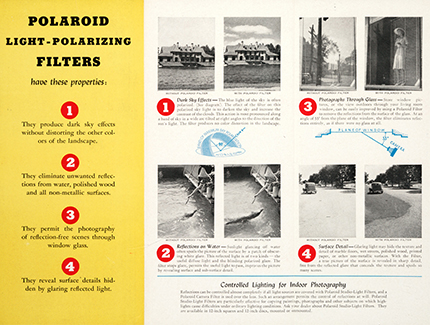

In addition to Polaroid Day Glasses and Polascreen camera filters, uses for Polaroid's polarizing filters included glare-free desk lamps, airplane windows, optical devices, educational kits for demonstrating the principles of light polarization, Polariscopes to detect strains or stresses in glass and other transparent materials, and the Polaroid Dermascope skin analyzer. Land's eloquent, charismatic style of presentation along with Polaroid's inviting advertising literature and product packaging bolstered sales. The company's colorful, easy-to-read promotional kits for its glare-free desk lamps, crafted by industrial designer Walter Dorwin Teague, advised sales people to use the full range of selling aids (folders, display cards, primers, demonstration lamps) and to run newspaper ads and test campaigns. Inviting advertisements touted the benefits of the "variable density" polarizing windows on the "Copper King" railcar of the Union Pacific streamliner City of Los Angeles, where leisure class passengers could adjust the amount of light coming in by rotating the inner window pane.

Strong sales particularly in sunglass lenses and camera filters enabled the nascent corporation to fund further research and development in other areas including 3-D motion picture film. At the New York World's Fair of 1939, a showcase of new American technology, visitors donned 3-D Polaroid spectacles to view a stereoscopic Polaroid motion picture, produced by the Chrysler Corporation. Entitled In Tune with Tomorrow, the film was shot with twin cameras by John Norling, a pioneer in 3-D movies. Polaroid sold more than 1.5 million stereo viewers for the film, which featured an automated assembly of a Plymouth car.

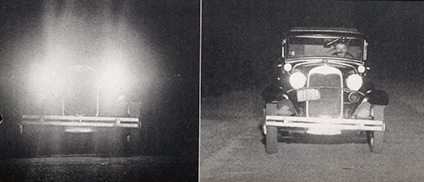

The use of polarizing filters to reduce headlight glare had occupied Land's thinking since the 1920s. "I didn't set out to make money but to get the polarizer used," he explained. "It would have saved 400 lives a night."18 He began discussions with automobile executives and engineers in 1932, including the head of General Motors research, Charles Kettering. Despite years of effort, Land ultimately failed to launch the headlight-polarizing product, as every car manufacturer would need to install new headlights and windshield glass and all U.S. states would require a change in product manufacturing. Land took away valuable lessons from the experience: "I knew then that I would never go into a commercial field that put a barrier between us and the customer."19 The young entrepreneur also realized that the success of his company depended on the continuation of its research efforts on a variety of fronts.

Patent protection enabled the Polaroid Corporation to successfully protect and market its products as well. Polaroid's patent lawyer Donald Brown explained that the company's policy had been "to finance research, development and expansion of business out of profits, and certainly the security provided by its patents has contributed greatly to the success of that policy."20 Land concurred: "It is impossible—without the protection of patents—for a new company working on a major advance in science or technology to (1) be properly financed; (2) go through the extremely difficult periods of study, invention, development, engineering, and production; or (3) afford to advertise and distribute its products and services."21

Land further understood the act of balancing basic and applied research while demonstrating accountability to the company's stockholders:

Our scientists get half of their time for themselves, to be free scientists, to think, to dream, to imagine . . . But the other half of the time, they . . . [apply] that whole scientific background they have built up to the daily problem of making scratch resistant sheets . . . of keeping the frame from warping, of getting dirt out of the lamination. . . . Whatever is necessary to make the whole gang of us do a better job for ourselves and for our customers. Now, the applied science division is based on that theory, and it draws on manufacturing, research, engineering, quality control. And its function is to hold costs down, push quality up, help get the new products out. 22

By the end of the 1930s, Polaroid emerged as a successful startup with a strong research component. Annual sales grew from $141,935 in 1937 to $1,032,425 in 1941.23 "Through the Depression, Polaroid's business remained small. But Land held on to a conviction that science pointed the way to products of the future," Forbes magazine noted. "By 1940, this confidence paid off."24 Land's experience in research and development, patents, sales, personnel, mass production, and marketing would serve him well in his subsequent breakthrough with instant photography. But in the early 1940s, the research and manufacturing efforts of the Polaroid Corporation would turn toward the war effort.

- 15. Edwin H. Land, "Research by the Business Itself," a paper contributed by Edwin H. Land, President, Polaroid Corporation, on the general subject of "The Future of Industrial Research" at the Standard Oil Development Company Forum held at the Waldorf Astoria, New York, October 5, 1944, 1, Edwin H. Land speech files, Polaroid Corporation Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 16. H. I. Day quoted in the New York Herald Tribune, "No-Glare Glass Is Shown Here by Inventor, 25," January 31, 1936, 34.

- 17. Polaroid also acquired the competing patents of the company Polarized Lights, which was working toward but had not yet produced a commercial product for reducing glare.

- 18. Land quoted in Richard Kostelanetz, "A Wide-Angle View and Close-Up Portrait of Edwin Land and His Polaroid Cameras," Lithopinion 9, no. 1 (Spring 1974): 55.

- 19. Ibid.

- 20. Donald L. Brown, "Protection Through Patents: The Polaroid Story," Journal of the Patent Office Society XLII, no. 7 (July 1960): 452.

- 21. Edwin H. Land, "Thinking Ahead," Harvard Business Review 37, no. 5 (September-October 1959): 147.

- 22. Edwin H. Land, "Dr. Edwin Land Christmas Party," 014681354_AT_0068_02 (side 2) audio file, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 23. "Income," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report to Stockholders 1937; "Net Sales and Income from Royalties, Research and Other Sources," Polaroid Corporation Annual Report 1941.

- 24. Forbes, "Ladies' Day at Polaroid," July 1, 1954, 24.