In 1944, Polaroid created a special project dedicated to instant photography, code named SX-70 ("SX" meaning Special Experiment).49 Land devoted massive efforts toward the secret project, which took place concurrently with other routine Polaroid manufacturing activities. Reams of daily research reports, diagrams, and test photographs in the Polaroid corporate archives reveal in breathtaking detail the evolution of the process as brilliantly envisioned and developed by Edwin Land and his dedicated project team. It required successful outcomes in a number of arenas, all of which would need to coalesce into an interrelated, sequentially timed series of self-activated chemical actions. "The kind of training we had given ourselves in the field of polarized light had endowed us with a competence we had not sought and did not know we had," Land wrote. "It was as if all that we had done in learning to make polarizers . . . had been a school and a preparation both for that first day in which I suddenly knew how to make a one-step dry photographic process and for the following three years in which we made the very vivid dream into a solid reality."50

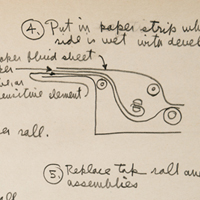

As the project began, employees submitted their findings, signed and witnessed, as a "Daily Report, SX-70," handwritten or typed onto a ditto master. Land's strong presence throughout the project comes through clearly in the reports, with frequent references such as "Mr. Land suggested" or "Mr. Land requested."51 William McCune remembered in the early experiments, "They were rather elegant concepts, intellectually, tested with rather simple techniques. . . . Land would talk to the laboratory people several times a day and look at what had happened and then suggest some new experiments to do and of course the technicians would also have their own ideas."52 In an early report dated December 18 and 19, 1943, Joseph Mahler, who had worked with Vectographs during the war effort, signed off on an experiment conducted by researcher Eudoxia Muller in which she transferred a negative onto a positive image.53 One of Clarence Kennedy's students who graduated from Smith College, Muller had also been involved in the production of Vectographs, a process that entailed the use of a roller to deposit an image on a film base—similar to the way instant photography would employ rollers in the development of the process.54

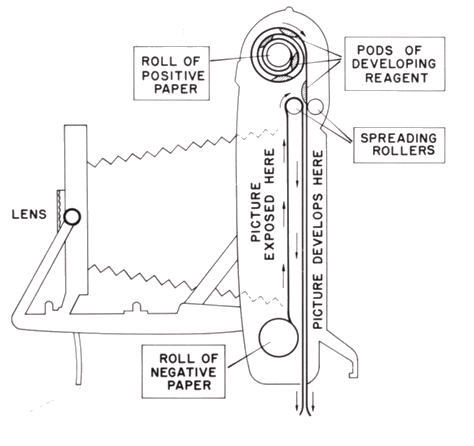

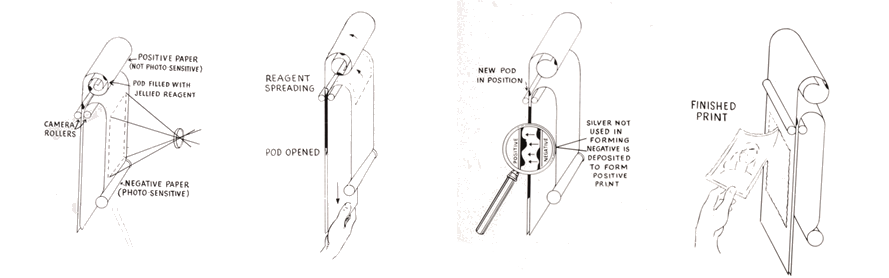

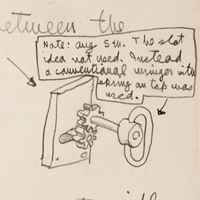

Maxfield Parrish, Jr., the son of the artist Maxfield Parrish, developed the design of a prototype model camera that housed a negative and a positive sheet on two separate rollers. His drawings, often produced in whimsical renderings, illustrate the mechanisms of the system.55 The negative moved past the lens box during exposure and made contact with the positive. As the sheets pressed together through another set of rollers, a pod, attached to the positive sheet, distributed a thinly spread viscous reagent that developed the negative and positive. Frederick J. Binda worked on the creation of the chemical pod that developed the negative and positive. The pod contained a developer (hydroquinone), an alkali to activate the developer, and a standard fixing agent (hypo). Another set of rollers squeezed the negative-positive sandwich out of the camera, and a dry positive print was peeled away from the negative.

Traditional photographic processing washed away the unexposed, undeveloped silver halide in the negative. Part of the brilliance of Land's process lay in rethinking the use of the unexposed crystals. In his instant photography process, a hypo solution carried the silver from the dissolved grains and deposited it on the receiving sheet to form a positive print. Stabilizing compounds in the pod diffused into the image layer at the end of processing to neutralize the residual reagent, bring the processing action to a stop, form a protective surface layer, and create a stable, long-lasting print.

The pod would have to release just the right amount of reagent in an evenly distributed, precisely timed manner that would not cause damage to the camera and also result in a dry print. The amount required, 1/20th of a cubic centimeter, would spread in a layer only a few thousandths of an inch in thickness. Experimenting with different film speeds, coatings, and color results, the team was able to increase the speed and sharpness of the film. They tested the process in temperatures ranging from 20 degrees F. (which required longer development) to 100 degrees F. (which required shorter development).

George Ehrenfried, a photographic physicist at Polaroid, remembered that "Land presided at a big custom-made semicircular desk . . . where he could sit and look out in all directions at the test samples, reports, and letters that covered it. He could watch technicians mixing viscous plastic concoctions."56 Ehrenfried explained that in "closet-sized dry darkrooms, [the team] assembled pods, pieces of ‘negative,' and pieces of ‘receiving sheet,' with masking tape, exposed the negative on a sensitometric light-box . . . and then ran the assembly through a motor-driven pair of rubber rollers. Two or three minutes later Land could look at the sample and decide what to do next." 57

"You always start with a fantasy," Land asserted. "Part of the fantasy technique is to visualize something as perfect. Then with the experiments you work back from the fantasy to reality, hacking away at the components."58 To that end, the SX-70 team took thousands of test photographs in order to rigorously experiment with the one-step process under a variety of conditions. Researchers annotated their test photographs with information about the test run, sheet, coating, pod, and exposure.

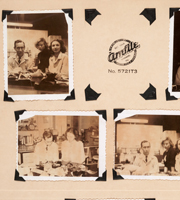

Describing his original one-step photographic process in 1949, Land reflected that while the realm of the investigation was scientific and technical, "the aesthetic purpose is to make available a new medium of expression to the numerous individuals who have an artistic interest in the world around them."59 In their early test photos, the research team also explored the expressive dimensions of the new medium. Among the popular subjects were pensive portraits of Land and playful snapshots of Polaroid colleagues. The team ventured outside the laboratory as well into the surrounding neighborhoods where they captured views of everyday life in post-war Cambridge and Boston—children, family, friends, pets, street scenes. These early Polaroid images, with their imperfect chemistry and varying shades of sepia tones, reveal the intimate, spontaneous quality of the process that would come to have a universal appeal.

- 48. Land, "On Some Conditions for Scientific Profundity in Industrial Research," 6.

- 49. SX-70 also referred to the camera system Polaroid introduced in 1972. The camera automatically ejected images that developed in the daylight without any chemical residue.

- 50. Land, "On Some Conditions for Scientific Profundity in Industrial Research," 6.

- 51. Polaroid Corporation Research and Development Records, Box III.328 and Box III.329, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 52. McCune, Oral history files, 41.

- 53. Polaroid Corporation Daily Report from Research Staff, December 18 and 19, 1943, written and signed by Eudoxia Muller, witnessed by Joseph Mahler, "SX-70 Record Notes 12/19/43 to 2/5/44" folder, Polaroid Corporation Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 54. Eudoxia Muller later married Dr. Robert Woodward, an organic chemist who worked as a consultant for Polaroid.

- 55. Polaroid Corporation Research and Development Records, Box III.329, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

- 56. George Ehrenfried, "Working with Land," in Optics and Photonics News 5, no. 10 (October 1994): 56.

- 57. Ibid.

- 58. Land quoted in Victor K. McElheny, "Edwin Herbert Land," Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 146, no. 1 (March 2002): 115.

- 59. Edwin H. Land, "One-Step Photography," The Photographic Journal (January 1950): 7.