I must say the Comprador has come out like a brick. I can count upon . . . certain $23,000.

— Albert Heard to John Heard, Hong Kong, February 28, 186322After the Opium War: Treaty Ports and Compradors

By the mid-1840s, the tightly controlled authority China had administered over its trade began to diminish. After the end of the First Opium War in 1842 and subsequent Treaty of Nanking, additional ports were open including the newly formed British colony of hong Kong. By 1843, the Canton trade system was fading out, and a new era of trade emerged in the recently opened treaty ports.

“Canton had been bombarded by the English and French forces . . . and the old factories, the scene of so much interest and happiness, were destroyed forever,” John Heard remembered of the aftermath of the Opium War. Of course, this settled the questions as to where we were to live in future. Hong-Kong had the call.23 Augustine Heard & Co. moved its main office to Hong Kong in 1857 and continued to expand its operations with branches in Foochow and Shanghai, agencies in Amoy and Ningbo, and later offices in Japan at Yokohama, Nagasaki, and Hyogo.

The period also signaled the end of the hong monopolies. The Chinese comprador, who served as a trading house employee and manager and sometimes as an independent merchant, became the essential go-between for American traders. Although neither party possessed complete control, the relationship proved mutually advantageous. “Acting as a middleman between two worlds, [the comprador] played a strategically important role in modern China’s economic growth, social change, and general acculturation,” historian Yen- P’ing Hao writes.24 Over time compradors also became investors in the foreign firms with which they did business and later founded their own enterprises.25

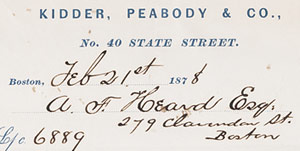

Augustine Heard retired from his role as active head of the company in 1844. He would never return to China. In June 1844, the firm announced its new partners: John Heard, George Basil Dixwell, and Joseph Roberts. Augustine Heard II arrived in 1847 and became a partner in 1850. Albert Heard came to China after graduating from Yale and became a partner in 1856, the same time that Augustine II went home and John returned to China to take his place. By 1857, John Heard reported that the company was turning profits of $180,000 to $200,000 a year.

The partners found that they could increasingly count on credit as a way of doing business, enabling them to acquire goods for American clients with far more capital than the company had. By 1860 the Heard & Co. purchases came to $1.5 million; 25 percent was funded through the firm’s money and the rest through credit.26 London merchant banks such as Baring Brothers & Co. provided Heard & Co. with credit, and the China trade in turn brought a significant increase in banking profits.27 “With the sophistication of credit instruments, it became more convenient for coastal merchants to obtain credit,” Yen-P’ing Hao maintains.28 The trading houses also heavily borrowed from compradors and traditional Chinese banking houses well into 1870s.