From the earliest days of trade between the United States and China, the major obstacle to this commerce had been the lack of American commodities that could be sold in China.

— Thomas Layton, The Voyage of the ’Frolic’: New England Merchants and the Opium Trade14Commodities, Currencies, and Balancing of the Trade Deficit

Augustine Heard & Co.’s formation occurred during the First Opium War (1839–1842). The conflict broke out between the United Kingdom and China in part over the transport and sale of opium by the British from India to China—a trade the Chinese Imperial government forbade. The English, who had vacated Canton, relied on American firms to oversee their transactions. Heard & Co. served in this capacity for one of the largest British firms, Jardine, Matheson & Co., and John Heard reported that the relationship brought in huge profits in annual commissions.15

Europeans had traded woolens, raw cotton, and sandalwood, while Americans exported otter skins, sandalwood, ginseng, and silver dollars (from Central and South America). But the Chinese demand for these imports did not anywhere equal the West’s desire for Chinese tea, silk, and fine porcelain. The British found they could address the growing trade deficit through opium from Bengal, India, where they owned plantations. Opium became more plentiful, and uses of the drug changed from originally medical purposes to recreational use.

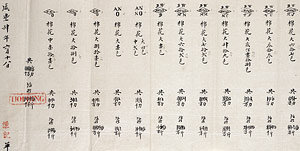

The drug represented 57 percent of all imports into China and also became a major source of currency.16 Millions of dollars’ worth of opium were imported into the country, distributed into the interior, and sold at retail shops and smoking houses. “Apart from criticizing the negative economic impact of the opium trade on its economy, Chinese government officials also tried to use the moral argument in their negotiations with the British,” Geoffrey Jones, Elisabeth Köll, and Alexis Gendron write in Opium and Entrepreneurship in the Nineteenth Century.17 After losing the First Opium War, the Chinese were unable to stop the trade. Americans first acquired opium from Turkey and then from India, where it was considered superior in quality.

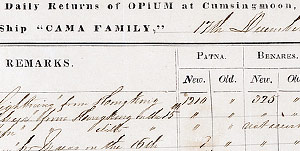

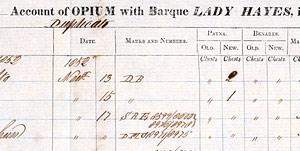

Augustine Heard & Co. used opium as payment to Chinese brokers for tea and silk, which would be purchased by American buyers. The firm traded in the drug early in the company’s history and also served as the agent for opium and tea trade for Jardine, Matheson & Co. during the First Opium War. (In comparison to large British houses, the Heard firm’s earnings from the opium trade were relatively small.)18 When Augustine Heard questioned the extent to which the company was involved in the opium trade, John Heard explained, “The opium business is the best business we have, not only from the direct, but for the collateral profit it induces. It also affords an excellent vent for exchange from America, rendering us independent of the demand for bills.”19 Heard & Co. continued to market opium in Canton, and by the 1850s Hong Kong became a center for opium trade.

Many Western traders were not aware that the outflow of silver from China was to cause a serious financial crisis for the Chinese.20 The Heard family, like other Western traders, came to China to realize their fortunes as quickly as possible and return home. In the insular treaty port communities and mercantile mindset in which they lived, they held themselves to a different standard regarding the moral implications of the opium trade. “China traders were rational, profit-maximizing entrepreneurs in Canton, where few pressures from family, custom, religion, or law restrained them,” Jacques Downs contends. “They had come to seek a fortune; they would wrest it from China and go home to practice their ethics.”21

![Doll and Richards invoice, January 23, [1877]. Heard Family Business Records. Harvard Business School.](images/site/pictures/menu5/066_thumb.jpg)