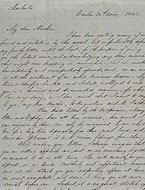

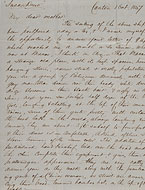

While reading your letters, I always imagine that you are sitting opposite me, and we are conversing together, as we used to do in old times.

— John Heard to Elizabeth Heard, 184256Influence of the China Trade and the Heard Legacy

The lives and prosperity of American traders in the China trade rippled out to and touched the society to which Western merchants overseas would eventually return. “Expatriates were the effective agents in transferring whatever was moved from China to America . . . goods, people, and influences,” Jacques Downs asserts.57 These exchanges and influences occurred through many channels—from the Chinese art and antiquities that Americans exported home, the ways in which wealthy traders gave back to their communities, and the archive of records merchants left behind that reveal a pivotal moment in Sino-Western relations.

Success in the China trade bestowed Western traders with a certain business and social prestige. American traders settled into fine country estates as well as elegant townhouses. Augustine Heard took pleasure in fixing up the beloved Ipswich home his father had built and also purchased a house in Boston. “I had often discussed with Uncle the expediency of my buying a house in town, in which all the family could be collected to live in the winter,” John Heard wrote. “He approved the idea, and I was not, therefore, much surprised when he told me one day that he had bought a house for $42,000. It was No. 3 Park Street, one of the best positions in Boston.”58

In addition to exposing American audiences to Chinese art through their export business, Western traders furnished their homes with Chinese paintings, watercolors, drawings, fine furniture, porcelain, lacquer ware, ivories, jade, draperies, scrolls, silk, and china—all of which constituted evidence of a family’s cultivated taste. Americans gained an appreciation for Chinese culture as well through expositions like the Centennial Exhibition of 1876 in Philadelphia where Chinese antiquities were displayed. The holdings of New England cultural institutions also included collections of Chinese art from mercantile families like the Heards.

Augustine Heard advised that money enabled one “to gratify his taste for literature and the fine arts, but most all, money was worth acquiring, from the amount of good which could be done by it.”59 He lived by his word, helping Ipswich soldiers and their families during the Civil War and donating to the Ipswich Female Seminary. While in China, reading became a favorite pastime of Western merchants, and many became known for their library collections. Not surprisingly, Augustine became the benefactor of the Ipswich Library, purchasing the land, donating the first 3,000 volumes, and creating an endowment.60 “The [library] building is like himself, strong, sturdy, substantial,” John Heard wrote of his uncle.61

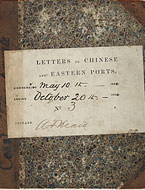

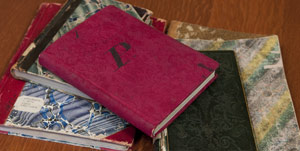

The Heard family legacy continues to survive through the rich archive of business records Augustine Heard & Co. preserved for posterity. The company kept shipping receipts, custom documents, export lists, telegrams, insurance vouchers, accounting books, ship designs, factory plans, and silk and paper samples. It saved incoming as well as outgoing correspondence, both originals and copies. In China, the firm did not own a copying press, and duplicates of correspondence were created by hand. Back home, Heard & Co. took care to bound duplicates made from a copying press into letter books.62

Personal letters, which could take up to five months to travel between China and the United States, served as a vital link, bringing welcome news of family members and life at home. As John Heard explained to his mother, “You write exactly as you speak, in a kind motherly and affectionate manner, and all the details you give me respecting affairs at home . . . serve to bring you all more vividly before me.”63 Western merchants captured their day-to-day existence in detailed descriptions of life in China. “First our long voyage, then the novelty of finding myself in a strange land, and among a strange and most singular people; forming new acquaintances, new habits; learning a new system of business,” John wrote.64 Countless diaries written by the Heards in China and years later back in New England provide equally illuminating reflections.

The vast, impeccable record preserved by the Heard family—800 volumes, 272 boxes, and 103 cartons—conveys a professional as well as a personal perspective on the China trade. Augustine Heard & Co. flourished at a moment when Westerners and Chinese were formulating diplomatic relationships and setting into place the business mechanisms that would bring China into the mainstream of world trade. “Both the positive and negative aspects of Western presence on the fringe of the empire resulted from the pressure of profit- minded foreign merchants,” Stephen Lockwood reasons. “It was entrepreneurs like the Heards who stood at these pivotal positions between two worlds writing a chapter in the history of each.”65

![Silk order, [June 20, 1860]. Heard Family Business Records. Harvard Business School.](images/site/pictures/menu11/121_thumb.jpg)