The China house was ultimately a go-between, an economic mediator spanning both geographic and cultural distance.

— Stephen Lockwood, Augustine Heard and Company, 1858-18622Doing Business with China: Early American Trading Houses

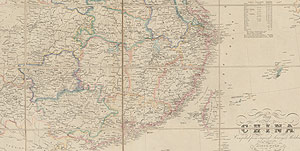

Western trade with China dates back to the 1500s, when Dutch and Portuguese traders began to import Chinese goods including silk, spices, porcelain, painting, and fine furniture. But it was the consumption of tea in Europe that created a booming commercial market between China and the West. Beginning in the seventeenth century, millions of pounds of Chinese tea were exported annually.

The Portuguese, the first European traders to enter China, leased and controlled Macao; by the 1700s the center of Western trade shifted to Canton (now Guangzhou). The Chinese government closely monitored activity in the trading ports. The United States made its foray into the China trade after independence from Great Britain and the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783. The following year the first American ship, Empress of China, arrived in China carrying silver and 30 tons of ginseng and sailed home loaded with tea and silk.

Europeans worked through centuries-old, joint stock trading enterprises such as the Dutch East India Company and the British East India Company. Americans, newly arrived in the China trade, operated as private traders or merchant syndicates that oversaw purchasing and shipping of goods from China to Western importers. “American merchants were bona fide free traders who were not restricted by a privileged incorporated monopoly,” historian Yen- p’ing Hao explains. “[They] were free to carry their cargoes wherever they pleased.”3

The American firm Russell & Co. was established in Canton in 1824 by Samuel Russell, who began as an apprentice clerk for a maritime merchant in Middletown, Connecticut. In 1830 Augustine Heard became a partner in the firm. Four years later, poor health forced Heard to return to Boston, where he remained actively involved in the business. Frictions within the company prompted Heard to form a new concern in 1840. Along with Russell & Co., Olyphant & Co., Perkins & Co., and W. S. Wetmore & Co., Augustine Heard & Co. became one of the largest American trading houses in China.