You were expected to be ready night or day, whenever you were wanted, and it was rare that I left my desk before 11 o’clock at night. Mr. Coolidge had a way of working in the evening, and my uncle of getting up early in the morning, so that between the two I got my full share.

— John Heard on life in Canton in the early 1840s, from his diary, 189146Expatriate Traders in the Treaty Port Communities

Westerners working at Augustine Heard & Co. and other trading firms formed tight-knit communities in China. American merchants had to acclimate themselves to the intricacies and nuances of the trading business as well as a foreign climate, diet, language, and occasional violence that erupted in the treaty ports.

In Canton, employees of Augustine Heard & Co lived essentially within the confines of what was known as a “factory.” The word “factory” denoted the place of business of the merchant or agent, who was called a “factor.” “We were not allowed to go beyond the limits of the factories (about a hundred yard square) except to the ’Hongs’ (places of business of the Hong merchants) and for exercise on the river,” John Heard wrote.47 When Heard & Co. later branched out into other ports, its employees enjoyed far greater freedom. “I prefer Hong Kong decidedly to Canton. Business was more easily carried on there, it is true, but [in Canton] there is . . . that sensation of restraint which was always more or less irksome,” John Heard argued. “You can walk, ride or drive here as far as you like, and there is a constant excitement of arrivals.”48

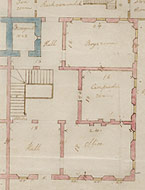

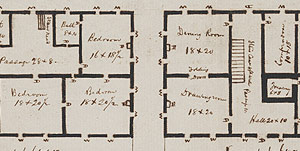

The factory served as office, storage, home, and place of recreation. The lower floors included the kitchen, treasury, servants’ quarters, and godowns (storage areas where goods were stored). Offices, parlors, and a dining room occupied the first floor, and bedrooms were on the upper floors. Eventually, the complexes expanded with residences and business offices in one building and compradors, other Chinese employees, and godowns in another. Foreign residences grew more comfortable with fine furniture, gardens, and aviaries. The good life enjoyed by American traders became possible through cheap Chinese labor and servants, who usually lived in the poor districts bordering on the wealthy areas.

The politics of empire and imperialism played out for Western traders for better or worse. While Americans reaped tremendous profits, after the First Opium War they also risked being a target as Westerners came to usurp the control the Chinese once maintained over their own trade. Fires, sometimes arson related, broke out. Episodes of social unrest also flared up. In a letter to his mother and father, John described in detail an attack on Augustine Heard & Co. on December 7, 1842 when a Chinese crowd pillaged and stole $250,000 from the company treasury. Augustine Heard led Western and Chinese employees out of the factory through the mob and safely aboard a ship. American soldiers then accompanied him back to the factory to save almost half the specie in the company treasury. Jacques Downs explains: “Violence was an intermittent but continuing feature of the period, and the presence of a senior partner with Heard’s renowned ’coolness and fearlessness’ in the face of danger provided an invaluable asset.”49 John Heard portrayed his uncle as having “a strong physique and equally strong temper and passions, but under the most perfect control. . . . I do not think he knew the sensation of fear.”50

Augustine Heard, Jr. depicted the foreign community of traders in China as “entirely masculine. . . . The men ate and drank a great deal too much.”51 (The Heards particularly enjoyed good wine.) In general, American women were notably absent from factory life, and if a Westerner got married back home his return to China was less likely. The Americans and British organized boat clubs, and regattas were held in the spring and autumn. John Heard remembered, “My uncle was very fond of rowing, and had a great opinion of it as an exercise. He accordingly bought an ordinary ship’s gig, about 18 feet long, in which he, Dixwell, and Roberts and myself went out every morning before breakfast.”52 Other recreational activities included billiards, bowling, cricket, fencing, amateur theatricals, and reading in lending libraries established in the treaty ports. Augustine Heard, Jr. explained that “it was the dream of all, partner or clerk, to ’get away to Macao for a week or two,’” a place Westerners appreciated for its European ambiance.53 “The hills and the Bay with its islands were as beautiful as ever,” John Heard wrote, “and looked like Paradise.”54

Western traders maintained close relationships with Chinese merchants and compradors. But their protected life in the treaty ports also created a narrow view of Chinese society and their impact on it. “Living as a privileged minority in well-upholstered comfort, insulated from, but extracting fortunes from various kinds of exploitation, Americans in treaty-ports could hardly be expected to develop enlightened social attitudes,” Downs asserts. “Because they saw their residence as temporary, and they knew that a fortune was self-justifying at home, Americans were less willing to disturb the mores of treaty-port culture.”55