Contemporary Black Artists

at Harvard Business School

This online exhibition highlights works of art from the HBS Art and Artifacts Collection and Schwartz Art Collection by Hurvin Anderson, Philip Kwame Apagya, Radcliffe Bailey, Rico Gatson, Tomashi Jackson, Whitfield Lovell, Lorraine O’ Grady, and Carrie Mae Weems. These diverse works by Black artists explore a range of themes, including the role of the artist in society, history, memory, civil rights, identity, and belonging. As part of Harvard Business School’s commitment to promoting racial equity, Contemporary Black Artists at Harvard Business School is meant to inspire both dialogue and change.

Exhibition curated by Melissa Renn, Collections Manager, HBS Art and Artifacts Collection.

CARRIE MAE WEEMS

(American, born 1953)

Untitled from The Louisiana Project, 2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.15

© 2021 Carrie Mae Weems

One of the most influential American artists in the contemporary art world, Carrie Mae Weems investigates family, gender, identity, race, sexism, class, politics, and power in her art. This photograph is from her series The Louisiana Project, commissioned in 2003 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase. In this series she uses photography, narrative, and video to delve into the social history of the Louisiana Purchase, casting herself in the image as a silent witness. In 2013, Weems received a MacArthur Fellowship as well as the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2015 she was the recipient of the W. E. B. Du Bois Medal at Harvard. In a New York Times review, critic Holland Cotter wrote, “Ms. Weems is what she has always been, a superb image maker and a moral force, focused and irrepressible.” The Schwartz Art Collection contains three other notable works by Weems: two photographs from her renowned Kitchen Table Series (2002.14 and 2002.15), and a work from 2003 titled Hush of Our Silence.

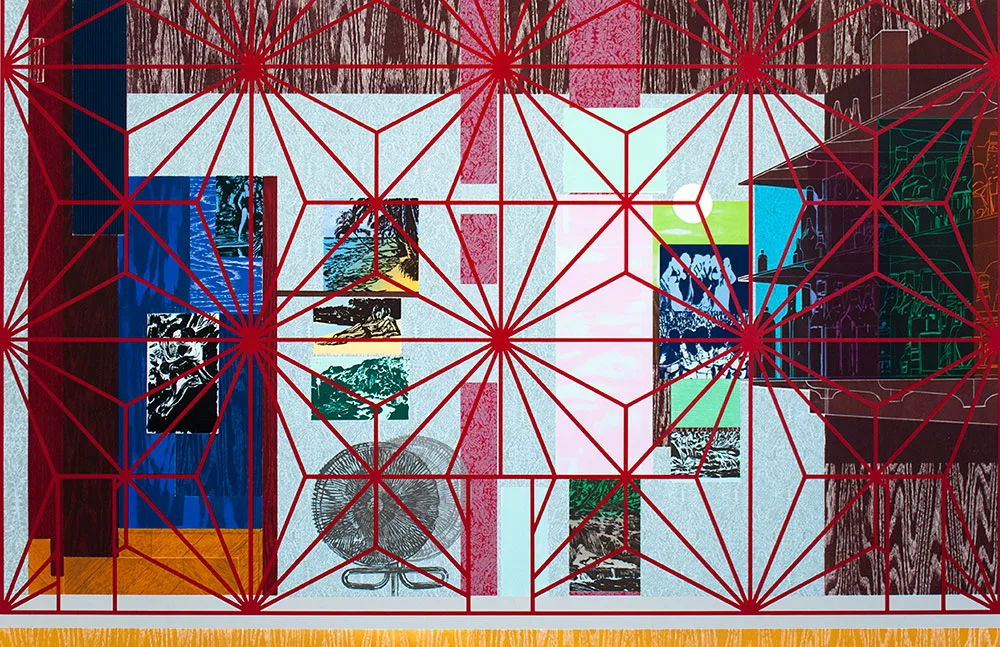

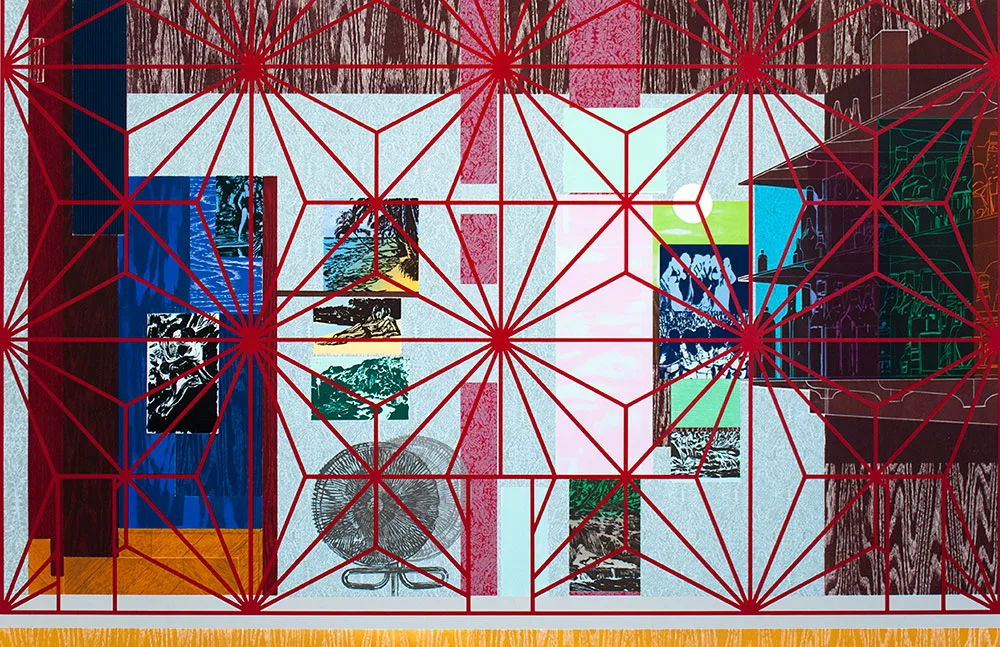

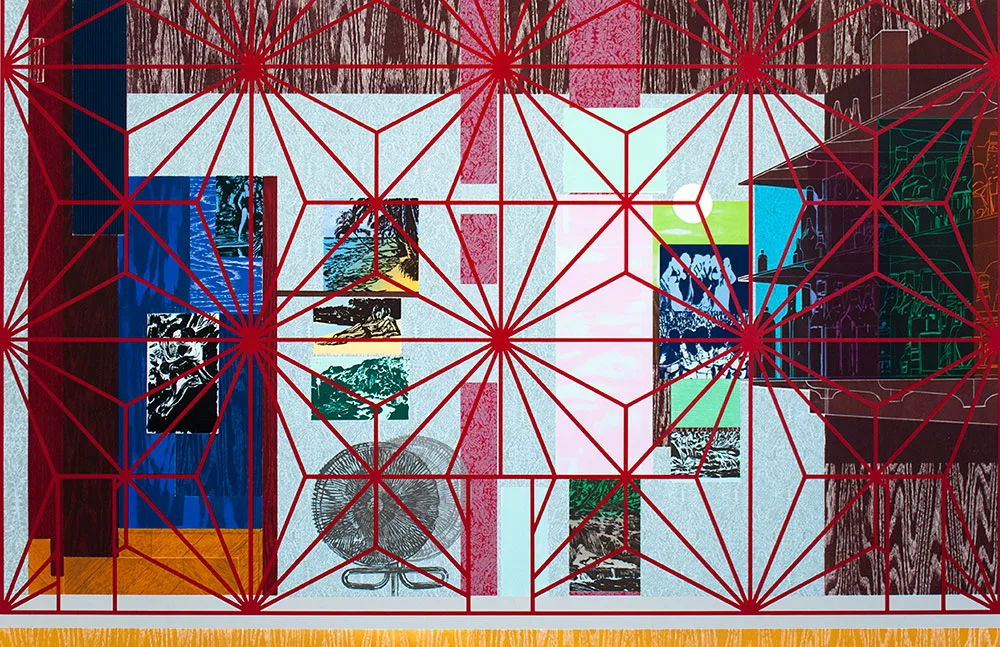

HURVIN ANDERSON

(British, born 1965)

Margaritas, 2014

Woodblock and screen print

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 2015.1

© 2021 Hurvin Anderson

Born in Birmingham, England, to Jamaican parents, Hurvin Anderson’s experience as a Black artist living in England has shaped much of his work. In his print Margaritas from the Welcome Series, Anderson grapples with his dual identity as both British and Jamaican. While at first glance this work may appear abstract, it is filled with many references to Jamaica and also to Trinidad, where he was an artist-in-residence in 2002. In Margaritas, the maroon lines represent a type of security grille used frequently on homes and businesses throughout the islands. The grille obscures and separates the viewer from the tropical images and colorful Caribbean scenes suspended in the background. A moving meditation on belonging and the challenge of reconnecting with one’s roots, this work expresses the artist’s feelings of living between two places. As Anderson stated in a 2020 Art Newspaper interview: “What is art for? For filling in the gaps. Some things can’t be said or explained but only expressed, and for that art will always be an essential part of communication, of passing on truths and memories and what it means to be human.”

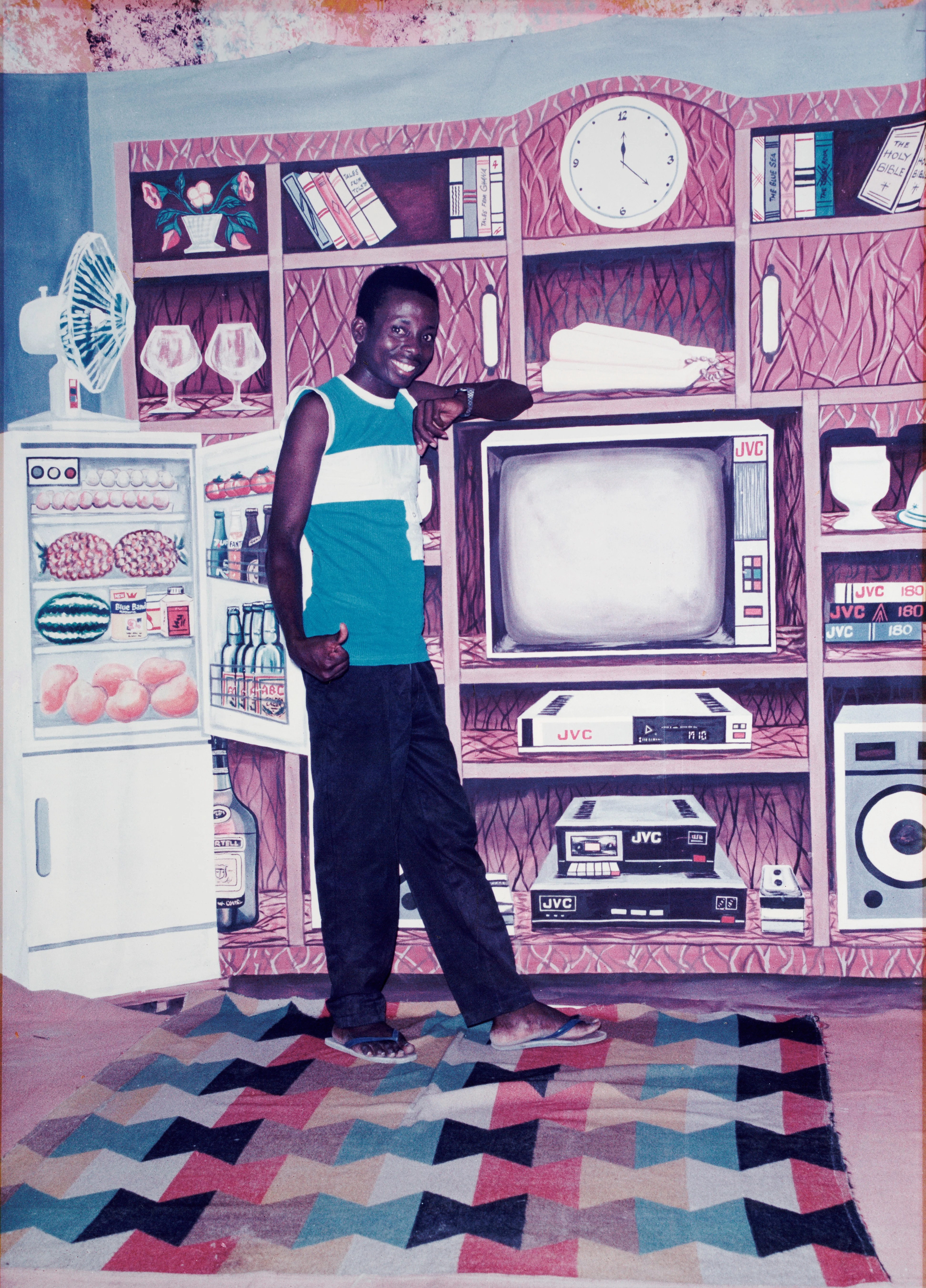

PHILIP KWAME APAGYA

(Ghanaian, born 1958)

Francis, 1996/2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.4

© 2021 Philip Kwame Apagya

Philip Kwame Apagya studied photojournalism at the Ghana Institute of Journalism. In 1982, he opened his own studio in Shama, on the west coast of Ghana. For his studio portraits, Apagya photographs his subject in front of a painted backdrop he constructs that portrays the sitter’s aspirations. Apagya explains: “I have always tried to find out what my clients like best, what they dream of, what they desire, their aspirations—particularly for the future: love, job, prosperity, a home of their own, everything that is prestigious and beautiful. I cannot but repeat that beauty is our business.” In this photograph, a boy named Francis pretends to lean against a painted image of a wooden entertainment center filled with books, speakers, a television, and electronics. At left is a painted image of a fully stocked refrigerator. Apagya’s works are both a contemplation of contemporary consumer culture and a reflection on the relationship between art and artifice, dreams and reality.

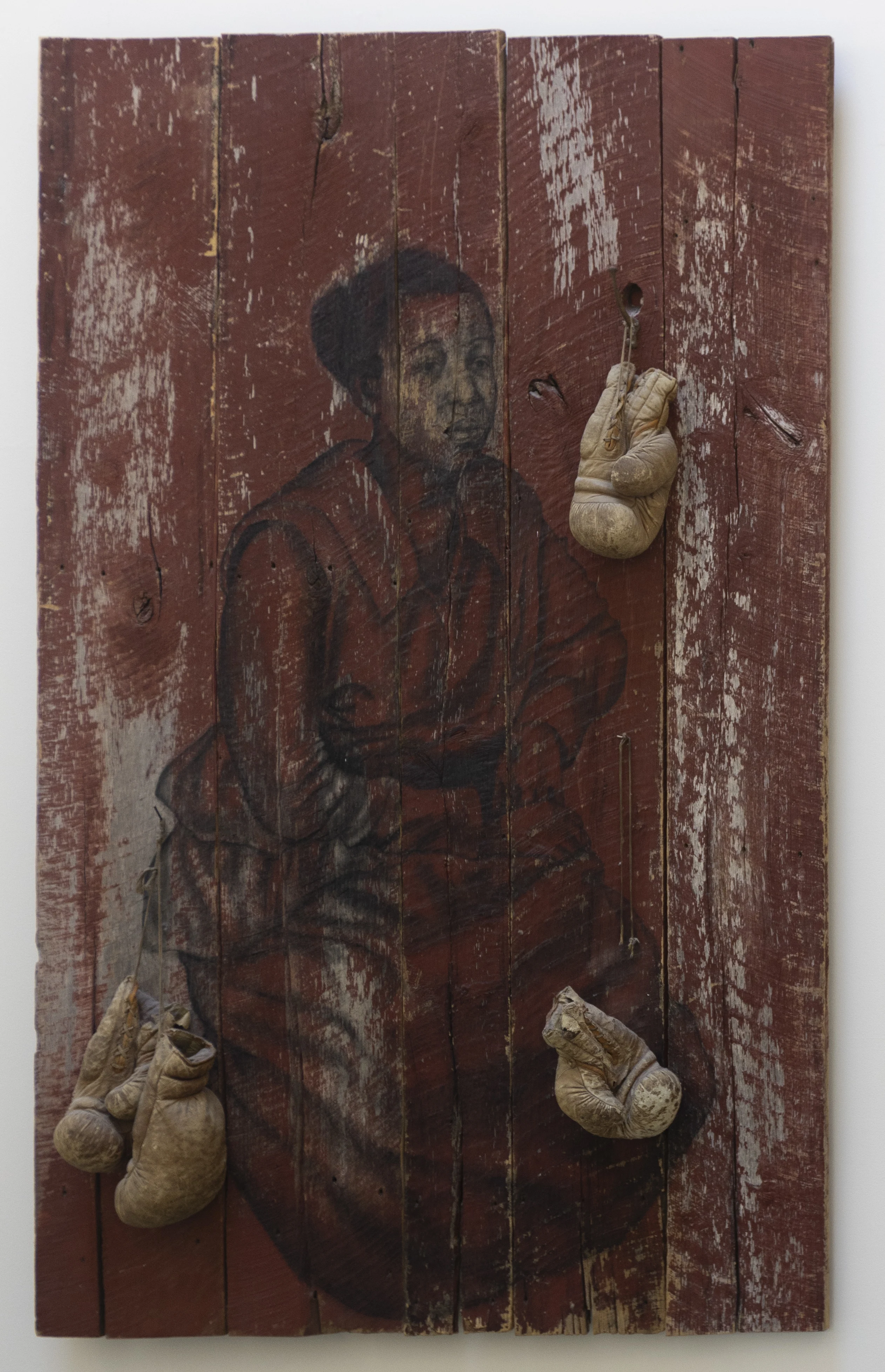

WHITFIELD LOVELL

(American, born 1959)

Strive, 2000

Charcoal on wood with found objects

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.12

© 2021 Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, and internationally renowned for his mixed-media installations that feature conté crayon and charcoal portraits of anonymous African Americans, Whitfield Lovell explores themes such as memory, identity, ancestry, and American history in his works. In Strive, Lovell used an image from his personal archive of family, vintage, and historical photographs as the source for his expressive drawing of a seated woman, which is rendered on found wood planks and surrounded by sets of actual boxing gloves. Lovell’s works such as Strive and prints including Barbados (also in the Schwartz Art Collection) bring the past into the present. He describes his aim as an artist: “I want to evoke the sense of place, [so one is] able to feel the spirit of the past for a moment, to feel the presence of these people. I want it to be a kind of ancestor worship. I want beliefs to be handed down.”

LORRAINE O’GRADY

(American, born 1934)

Four photographs from the series, Art Is…, 1983/2009

Chromogenic prints

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2016.5-8

© 2021 Lorraine O’Grady / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Is… (Star East Monuments), 1983/2009 (top left)

Art Is… (Women in Crowd Framed), 1983/2009 (top right)

Art Is… (Young Women Leaning on Barrier), 1983/2009 (lower left)

Art Is… (Dancer in Grass Skirt), 1983/2009 (lower right)

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, to West Indian parents, conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady received a BA from Wellesley College. These four photographs are from one of O’Grady’s most celebrated performances, Art Is..., which came about because of this comment made to her by an acquaintance: “Avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people.” In response, O’Grady decided to create a work of art for the largest Black space she could think of, the African American Day Parade in Harlem, New York. She entered a float with the words “Art Is...” painted on the platform’s gold skirt. On top of the float, she mounted a 9 x 15-foot gilded frame, built with the help of artists Richard DeGussi and George Mingo. As the float moved down Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, O’Grady’s fifteen collaborators, seen here dressed in white, invited people to pose in the empty gilded picture frames they carried. Onlookers became participants in both the parade and the work of art, many exclaiming, as the frames and float passed by: “Make me art!” and “We’re the art!” These photographs are not only documents of the event, but also compelling reminders of the power and joy of art.

HURVIN ANDERSON

(British, born 1965)

Margaritas, 2014

Woodblock and screen print

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 2015.1

© 2021 Hurvin Anderson

Born in Birmingham, England, to Jamaican parents, Hurvin Anderson’s experience as a Black artist living in England has shaped much of his work. In his print Margaritas from the Welcome Series, Anderson grapples with his dual identity as both British and Jamaican. While at first glance this work may appear abstract, it is filled with many references to Jamaica and also to Trinidad, where he was an artist-in-residence in 2002. In Margaritas, the maroon lines represent a type of security grille used frequently on homes and businesses throughout the islands. The grille obscures and separates the viewer from the tropical images and colorful Caribbean scenes suspended in the background. A moving meditation on belonging and the challenge of reconnecting with one’s roots, this work expresses the artist’s feelings of living between two places. As Anderson stated in a 2020 Art Newspaper interview: “What is art for? For filling in the gaps. Some things can’t be said or explained but only expressed, and for that art will always be an essential part of communication, of passing on truths and memories and what it means to be human.”

PHILIP KWAME APAGYA

(Ghanaian, born 1958)

Francis, 1996/2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.4

© 2021 Philip Kwame Apagya

Philip Kwame Apagya studied photojournalism at the Ghana Institute of Journalism. In 1982, he opened his own studio in Shama, on the west coast of Ghana. For his studio portraits, Apagya photographs his subject in front of a painted backdrop he constructs that portrays the sitter’s aspirations. Apagya explains: “I have always tried to find out what my clients like best, what they dream of, what they desire, their aspirations—particularly for the future: love, job, prosperity, a home of their own, everything that is prestigious and beautiful. I cannot but repeat that beauty is our business.” In this photograph, a boy named Francis pretends to lean against a painted image of a wooden entertainment center filled with books, speakers, a television, and electronics. At left is a painted image of a fully stocked refrigerator. Apagya’s works are both a contemplation of contemporary consumer culture and a reflection on the relationship between art and artifice, dreams and reality.

WHITFIELD LOVELL

(American, born 1959)

Strive, 2000

Charcoal on wood with found objects

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.12

© 2021 Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, and internationally renowned for his mixed-media installations that feature conté crayon and charcoal portraits of anonymous African Americans, Whitfield Lovell explores themes such as memory, identity, ancestry, and American history in his works. In Strive, Lovell used an image from his personal archive of family, vintage, and historical photographs as the source for his expressive drawing of a seated woman, which is rendered on found wood planks and surrounded by sets of actual boxing gloves. Lovell’s works such as Strive and prints including Barbados (also in the Schwartz Art Collection) bring the past into the present. He describes his aim as an artist: “I want to evoke the sense of place, [so one is] able to feel the spirit of the past for a moment, to feel the presence of these people. I want it to be a kind of ancestor worship. I want beliefs to be handed down.”

LORRAINE O’GRADY

(American, born 1934)

Four photographs from the series, Art Is…, 1983/2009

Chromogenic prints

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2016.5-8

© 2021 Lorraine O’Grady / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Is… (Star East Monuments), 1983/2009 (top left)

Art Is… (Women in Crowd Framed), 1983/2009 (top right)

Art Is… (Young Women Leaning on Barrier), 1983/2009 (lower left)

Art Is… (Dancer in Grass Skirt), 1983/2009 (lower right)

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, to West Indian parents, conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady received a BA from Wellesley College. These four photographs are from one of O’Grady’s most celebrated performances, Art Is..., which came about because of this comment made to her by an acquaintance: “Avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people.” In response, O’Grady decided to create a work of art for the largest Black space she could think of, the African American Day Parade in Harlem, New York. She entered a float with the words “Art Is...” painted on the platform’s gold skirt. On top of the float, she mounted a 9 x 15-foot gilded frame, built with the help of artists Richard DeGussi and George Mingo. As the float moved down Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, O’Grady’s fifteen collaborators, seen here dressed in white, invited people to pose in the empty gilded picture frames they carried. Onlookers became participants in both the parade and the work of art, many exclaiming, as the frames and float passed by: “Make me art!” and “We’re the art!” These photographs are not only documents of the event, but also compelling reminders of the power and joy of art.

CARRIE MAE WEEMS

(American, born 1953)

Untitled from The Louisiana Project, 2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.15

© 2021 Carrie Mae Weems

One of the most influential American artists in the contemporary art world, Carrie Mae Weems investigates family, gender, identity, race, sexism, class, politics, and power in her art. This photograph is from her series The Louisiana Project, commissioned in 2003 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase. In this series she uses photography, narrative, and video to delve into the social history of the Louisiana Purchase, casting herself in the image as a silent witness. In 2013, Weems received a MacArthur Fellowship as well as the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2015 she was the recipient of the W. E. B. Du Bois Medal at Harvard. In a New York Times review, critic Holland Cotter wrote, “Ms. Weems is what she has always been, a superb image maker and a moral force, focused and irrepressible.” The Schwartz Art Collection contains three other notable works by Weems: two photographs from her renowned Kitchen Table Series (2002.14 and 2002.15), and a work from 2003 titled Hush of Our Silence.

PHILIP KWAME APAGYA

(Ghanaian, born 1958)

Francis, 1996/2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.4

© 2021 Philip Kwame Apagya

Philip Kwame Apagya studied photojournalism at the Ghana Institute of Journalism. In 1982, he opened his own studio in Shama, on the west coast of Ghana. For his studio portraits, Apagya photographs his subject in front of a painted backdrop he constructs that portrays the sitter’s aspirations. Apagya explains: “I have always tried to find out what my clients like best, what they dream of, what they desire, their aspirations—particularly for the future: love, job, prosperity, a home of their own, everything that is prestigious and beautiful. I cannot but repeat that beauty is our business.” In this photograph, a boy named Francis pretends to lean against a painted image of a wooden entertainment center filled with books, speakers, a television, and electronics. At left is a painted image of a fully stocked refrigerator. Apagya’s works are both a contemplation of contemporary consumer culture and a reflection on the relationship between art and artifice, dreams and reality.

WHITFIELD LOVELL

(American, born 1959)

Strive, 2000

Charcoal on wood with found objects

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.12

© 2021 Whitfield Lovell. Courtesy DC Moore Gallery, New York

The recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, and internationally renowned for his mixed-media installations that feature conté crayon and charcoal portraits of anonymous African Americans, Whitfield Lovell explores themes such as memory, identity, ancestry, and American history in his works. In Strive, Lovell used an image from his personal archive of family, vintage, and historical photographs as the source for his expressive drawing of a seated woman, which is rendered on found wood planks and surrounded by sets of actual boxing gloves. Lovell’s works such as Strive and prints including Barbados (also in the Schwartz Art Collection) bring the past into the present. He describes his aim as an artist: “I want to evoke the sense of place, [so one is] able to feel the spirit of the past for a moment, to feel the presence of these people. I want it to be a kind of ancestor worship. I want beliefs to be handed down.”

LORRAINE O’GRADY

(American, born 1934)

Four photographs from the series, Art Is…, 1983/2009

Chromogenic prints

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2016.5-8

© 2021 Lorraine O’Grady / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Art Is… (Star East Monuments), 1983/2009 (top left)

Art Is… (Women in Crowd Framed), 1983/2009 (top right)

Art Is… (Young Women Leaning on Barrier), 1983/2009 (lower left)

Art Is… (Dancer in Grass Skirt), 1983/2009 (lower right)

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, to West Indian parents, conceptual artist Lorraine O’Grady received a BA from Wellesley College. These four photographs are from one of O’Grady’s most celebrated performances, Art Is..., which came about because of this comment made to her by an acquaintance: “Avant-garde art doesn’t have anything to do with Black people.” In response, O’Grady decided to create a work of art for the largest Black space she could think of, the African American Day Parade in Harlem, New York. She entered a float with the words “Art Is...” painted on the platform’s gold skirt. On top of the float, she mounted a 9 x 15-foot gilded frame, built with the help of artists Richard DeGussi and George Mingo. As the float moved down Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard, O’Grady’s fifteen collaborators, seen here dressed in white, invited people to pose in the empty gilded picture frames they carried. Onlookers became participants in both the parade and the work of art, many exclaiming, as the frames and float passed by: “Make me art!” and “We’re the art!” These photographs are not only documents of the event, but also compelling reminders of the power and joy of art.

CARRIE MAE WEEMS

(American, born 1953)

Untitled from The Louisiana Project, 2003

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2004.15

© 2021 Carrie Mae Weems

One of the most influential American artists in the contemporary art world, Carrie Mae Weems investigates family, gender, identity, race, sexism, class, politics, and power in her art. This photograph is from her series The Louisiana Project, commissioned in 2003 to commemorate the bicentennial of the Louisiana Purchase. In this series she uses photography, narrative, and video to delve into the social history of the Louisiana Purchase, casting herself in the image as a silent witness. In 2013, Weems received a MacArthur Fellowship as well as the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation’s Lifetime Achievement Award, and in 2015 she was the recipient of the W. E. B. Du Bois Medal at Harvard. In a New York Times review, critic Holland Cotter wrote, “Ms. Weems is what she has always been, a superb image maker and a moral force, focused and irrepressible.” The Schwartz Art Collection contains three other notable works by Weems: two photographs from her renowned Kitchen Table Series (2002.14 and 2002.15), and a work from 2003 titled Hush of Our Silence.

HURVIN ANDERSON

(British, born 1965)

Margaritas, 2014

Woodblock and screen print

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 2015.1

© 2021 Hurvin Anderson

Born in Birmingham, England, to Jamaican parents, Hurvin Anderson’s experience as a Black artist living in England has shaped much of his work. In his print Margaritas from the Welcome Series, Anderson grapples with his dual identity as both British and Jamaican. While at first glance this work may appear abstract, it is filled with many references to Jamaica and also to Trinidad, where he was an artist-in-residence in 2002. In Margaritas, the maroon lines represent a type of security grille used frequently on homes and businesses throughout the islands. The grille obscures and separates the viewer from the tropical images and colorful Caribbean scenes suspended in the background. A moving meditation on belonging and the challenge of reconnecting with one’s roots, this work expresses the artist’s feelings of living between two places. As Anderson stated in a 2020 Art Newspaper interview: “What is art for? For filling in the gaps. Some things can’t be said or explained but only expressed, and for that art will always be an essential part of communication, of passing on truths and memories and what it means to be human.”

These collections are available for use in the de Gaspé Beaubien Reading Room.

Our team is here to help.