Research in Black and White

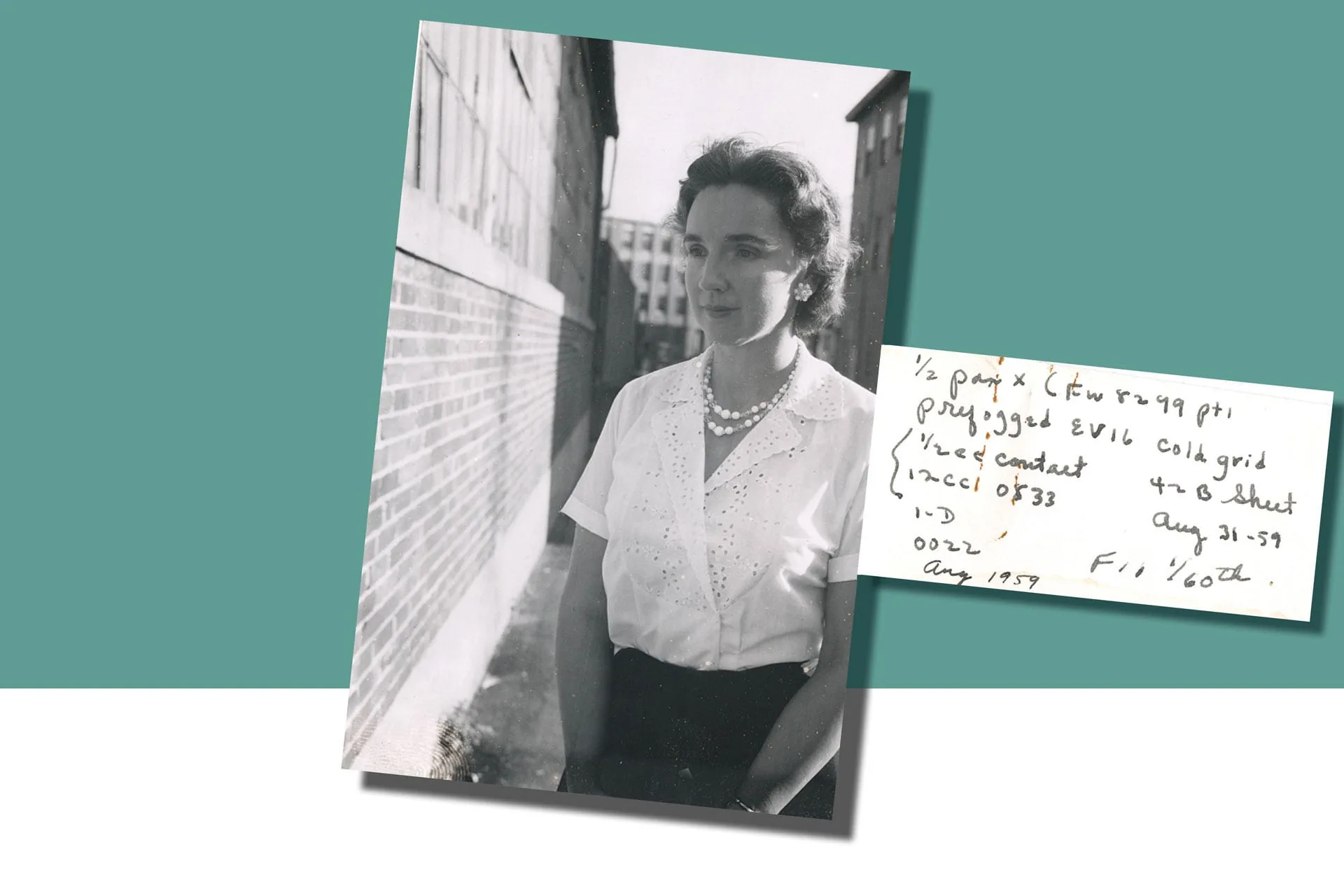

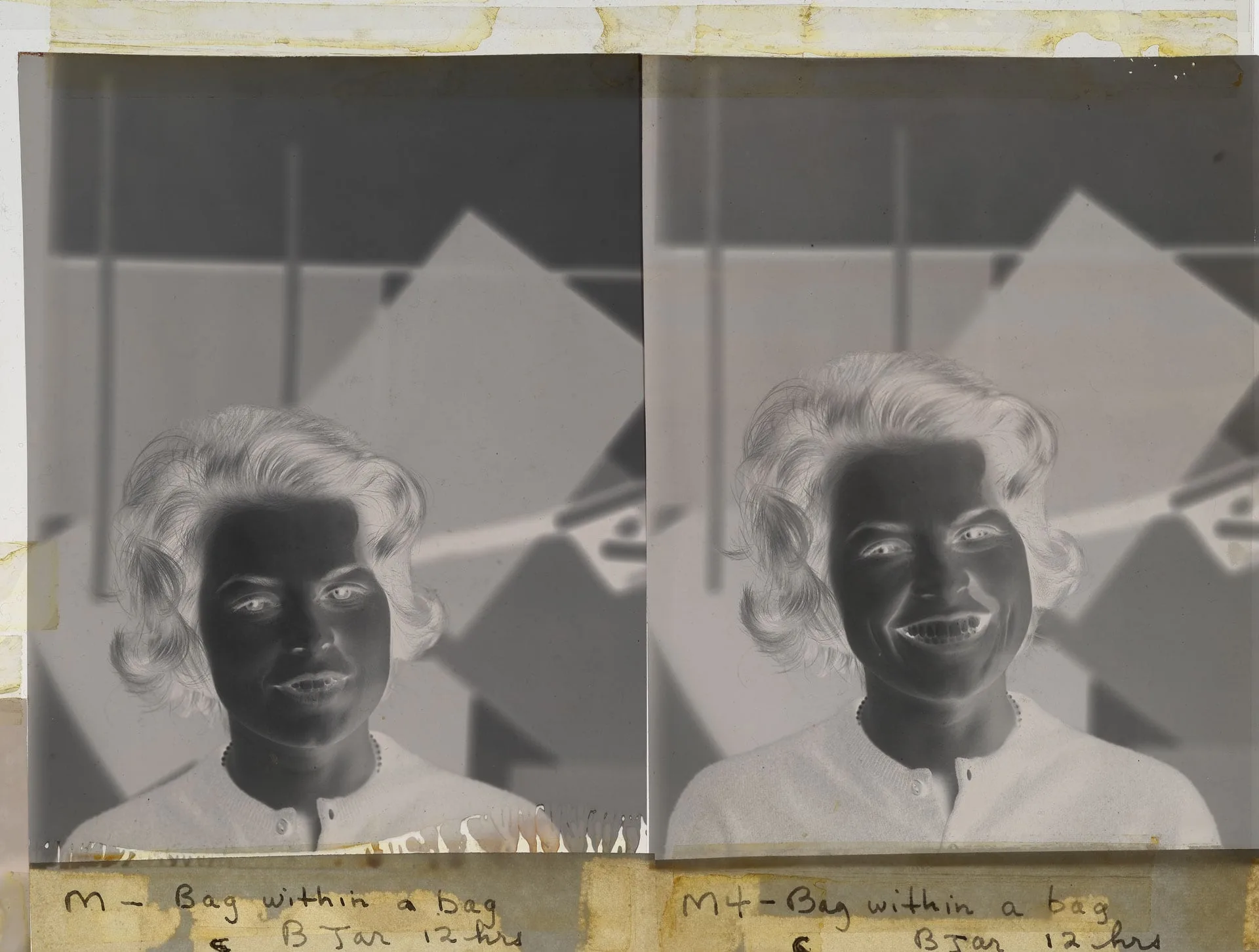

Photo: Meroë Morse, test photograph, August 1959. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.83, f. 15.

In 1948, only a few years after starting at Polaroid, Meroë Morse became the laboratory supervisor responsible for photographic materials. The earliest Polaroid film, Type 40, produced sepia-toned prints that had limited tonal range. Morse and her lab would next focus on producing black-and-white images that exhibited greater detail, a wider tonal range, and a color palette more familiar and appealing to consumers.(1) In 1950, after two years of intensive work, the company introduced black-and-white film Type 41, with a film speed of ASA 100. The film produced prints that exhibited finer detail and, as U.S. Camera enthused, created “pictures-in-a-minute of exceptional tonal values.”(2) The Detroit Free Press reported that Land credited Morse with “valuable assistance in research that led to the new film.”(3)

Two girls, test photograph, Type 40, November 6, 1946. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Edwin H. Land, b. V.31, f. 19.

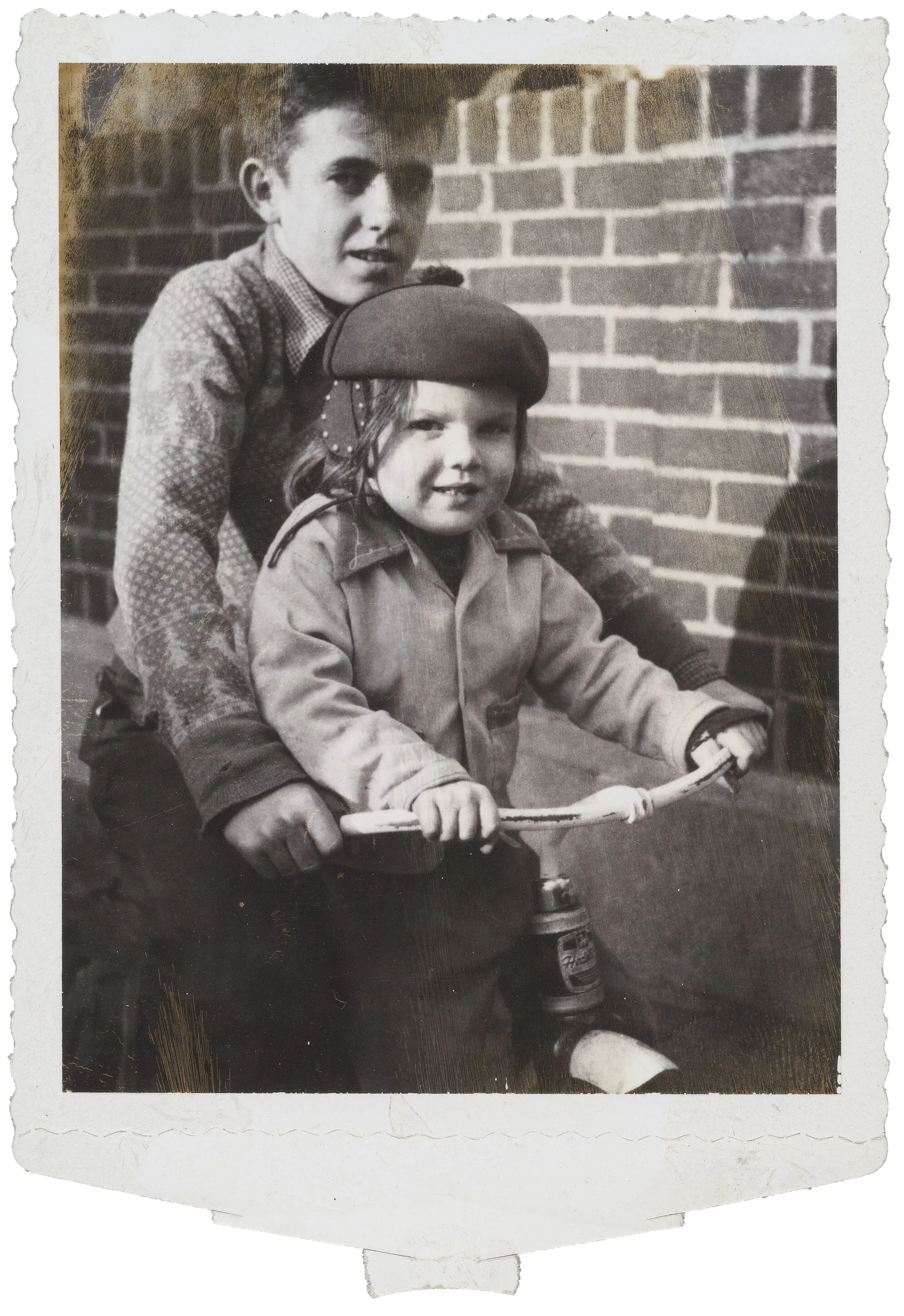

Girl and boy on bike, test photograph, Type 41, ca. 1950s. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Edwin H. Land, b. V.33, f. 19.

Test photographs taken by Polaroid employees capture the close quarters and camaraderie of the company’s Cambridge laboratory, where early experiments in instant photography took place. Peter C. Wensberg, Polaroid's senior vice president for marketing, explained that many of those working in the lab “had graduated from Smith, some with no scientific background. Land proved many times over that a bright young liberal arts student could learn the routines of the laboratory and the structure of a scientific discipline as rapidly as applicants with technical experience. He liked the fact that his students had little to unlearn.”(4) William McCune, who started as a quality control officer and later became chairman of Polaroid, wrote, “So many extraordinary people who were not scientists found Polaroid an interesting place to work and contributed to the creative nature of the company in its early days. . . . That’s an unusual kind of thing for a small company, particularly when it’s based primarily on science.”(5)

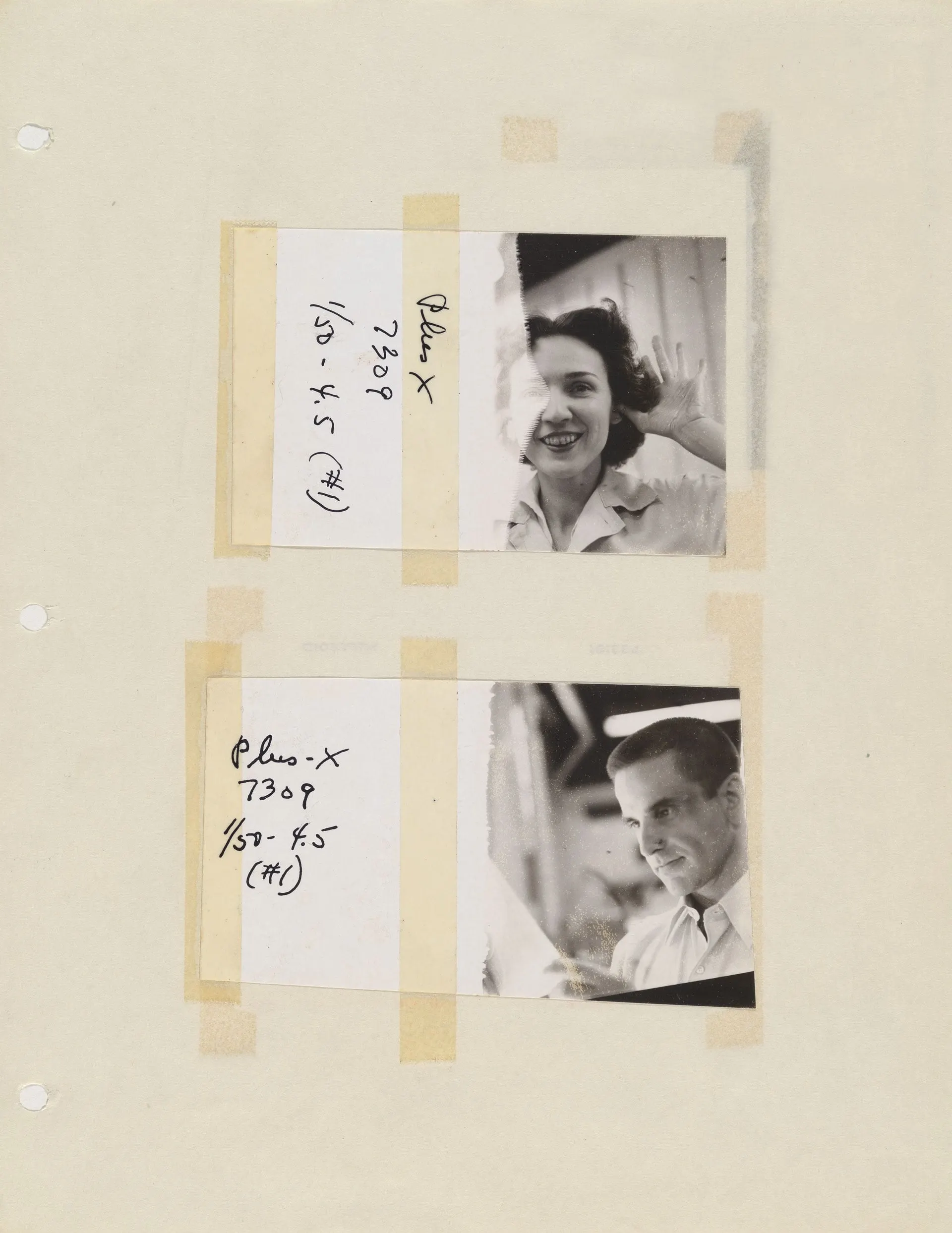

Meroë Morse, Howard Rogers, test photographs, Plus X, ca. 1950s. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.37, f. 12.

Taking advantage of Polaroid’s support for education, Morse attended courses in chemistry at Harvard and MIT.(6) The Polaroid Research Seminars in the Organic Research Lab also offered classes in organic chemistry and organic chemical theory, and employees could reference books and journals on chemistry, physics, optics, and photography in the company’s impressive library.(7)

Mary McCann, who joined Polaroid in 1960 after receiving a BS in chemical engineering from Tufts University, first worked with Howard Rogers, director of Polaroid color film research.(8) She remembers, “Polaroid’s black-and-white and color labs used high-efficiency, rapid turnaround techniques to make evaluations in minutes or hours, rather than weeks or months. The teams included chemists, artists, and those with other interests. Their task in evaluation was both numerical (taking reflectance measurements of the film’s response to light) and aesthetic (recording impressions of the print’s transformation of the scene).” McCann adds that “This amalgam of skills in chemistry, physics, and aesthetics was created by the breadth of backgrounds in the team, [and] all participated together in this evaluation process.”(9)

In the early days, Land had personal contact with much of his staff. He also encouraged the exchange of information among groups focused on different problems. To this end, Polaroid implemented a sun/satellite system: an employee could serve as a sun supported by satellites or as a satellite supporting a sun in another area. Morse explained that in the sun-and-satellite organization, “we all shift our ‘orbits’ almost daily.”(10) Inge Reethof, senior technical specialist, recalled the “happy” interactions “every day that you go into work” and that the work was “always very enriching.”(11)

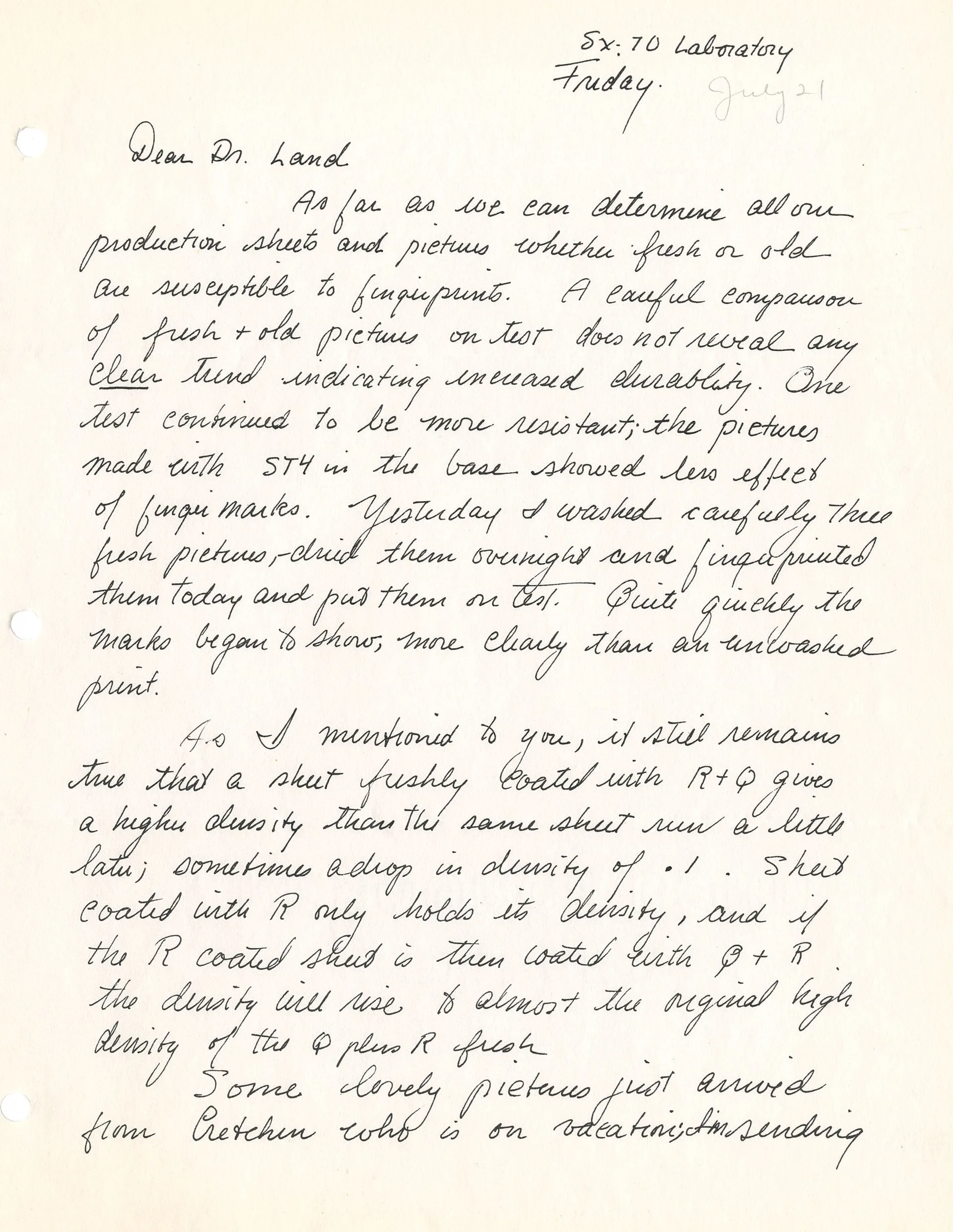

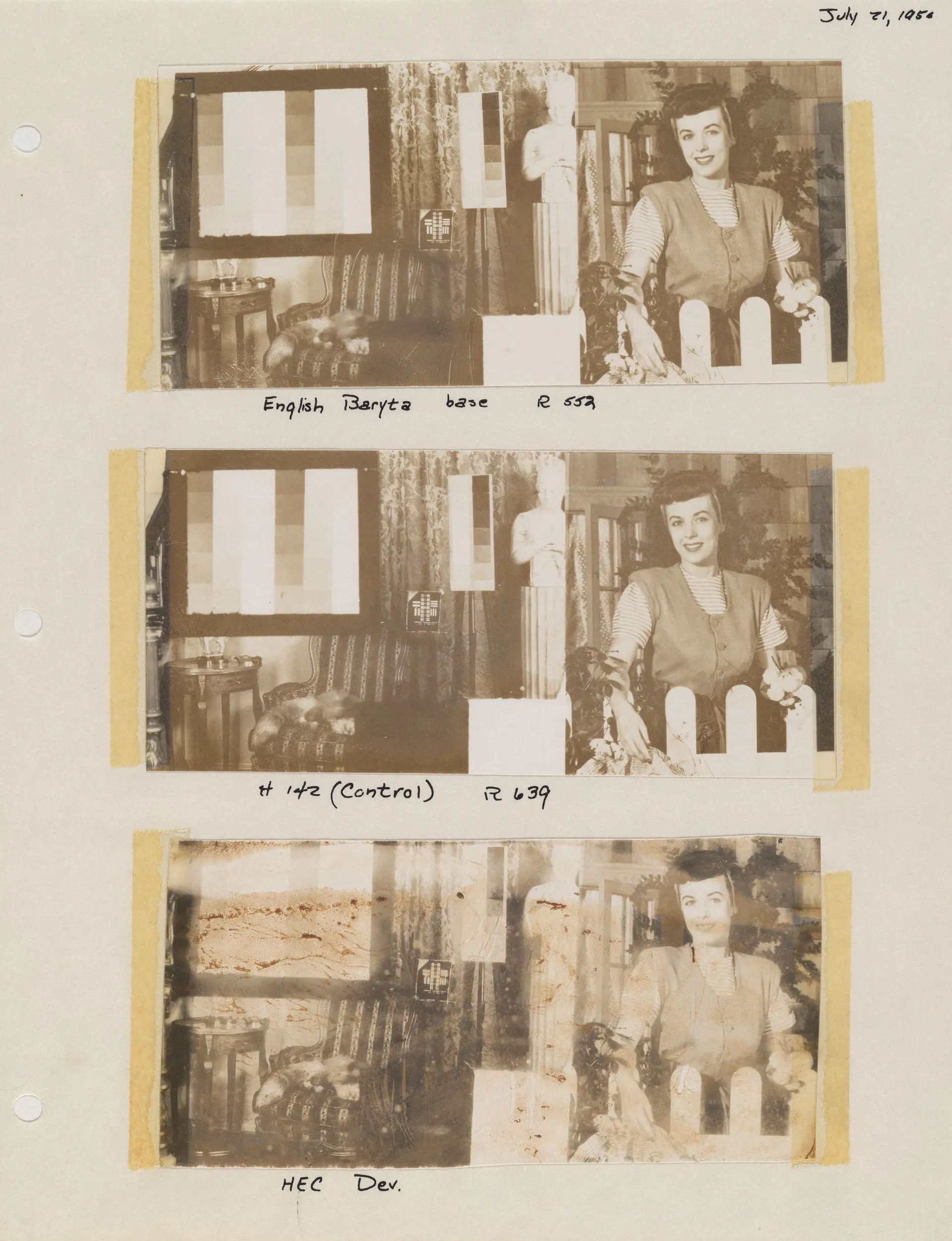

Report, Meroë Morse to Edwin Land, SX-70 Laboratory, Friday, July 21, 1950. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.3, f. 12.

Morse and her colleagues submitted thousands of handwritten or typed reports and test photographs that conveyed the technical and aesthetic findings of their experiments. Land understood that through experimentation even repeated failure yielded data that would ultimately lead to the successful testing of hypotheses. He believed his employees needed time for the concentration required in the robust and exhaustive evaluation of a hypothesis. “I find it is very important to work intensively for long hours when I am beginning to see solutions to a problem,” he argued. “You are handling so many variables at a barely conscious level that you can’t afford to be interrupted. If you are, it may take a year to cover the same ground you could otherwise cover in sixty hours.”(12) Wensberg remembered that “Land hated to stop working. Once begun on a course of action, he wanted to experiment until the hypothesis was proved. He would not entertain the assumption that his hypothesis might be disprovable until and unless it was actually disproved. He worked like a predator, stalking a solution, a proof, with perpetual patience and perpetual energy.”(13)

Morse proved equally determined and indefatigable. “A day is all too short,” she lamented to Land. “It always seems to me that we just really get warmed up to our problems and then it’s time to quit.”(14) Matching Land’s drive and energy, she kept long working hours. Morse apologized to Land for her handwritten reports, noting she only got to “summarizing the days experiments at 5:30–6:30 and do not like to keep a secretary another hour after that.”(15) She appreciated the ups and downs of life in the laboratory. “Today is an ‘Oh be joyful day,’ at least in contrast to yesterday,” she wrote to Land, “The production mix is . . . promising.”(16)

Test photographs, Meroë Morse to Edwin Land, SX-70 Laboratory, Friday, July 21, 1950. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, b. VII.3, f. 12.

When Polaroid introduced Type 41 black-and-white film in 1950, the company faced a major crisis. Within the first six months, the prints with their deckle edges and white borders tended to fade and discolor. To address mounting customer complaints, Morse’s lab collaborated with Elkan Blout, a biochemist and Polaroid’s associate director of research, to create a film coater. The coater, included in every film pack and applied by consumers to their images with a swab, served as a washing solution that stopped further development of the film and provided a protective coating for the print. Morse described the complex character of the chemical mixture, which needed to be “easily applicable, giving a smooth, shiny, clear, continuous film . . . [and] dry quickly to a state which is not tacky.”(17)

In 1955, Morse became manager of black-and-white photographic research, where she earned a reputation as a skilled supervisor of a major research group. Her lab succeeded in producing ever-faster films—including Type 42 (ASA 200) and Type 44 (ASA 400)—that allowed customers to take photographs in lower-light conditions indoors or on overcast days and to more easily capture moving subjects. Available in 1959, Type 47 film (ASA 3,000), the fastest speed for general photography at the time, made it possible to shoot indoor scenes without a flash and produced black-and-white prints with greater tonal range and brilliance. In 1961, Polaroid introduced Type 55 P/N film for large-format cameras. This development was of special interest to professional photographers because the new commercial film produced, for the first time at Polaroid, reusable 4×5 negatives from which multiple prints and enlargements could be made.(18)

Negative test photographs, Type 55 P/N, 1961. Polaroid Corporation Research & Development Records, b. III.350, f. 3.

In addition to the original Land Camera Model 95, Polaroid introduced the Pathfinder Model 110, marketed for professional use, in 1952; the smaller Highlander Model 80 in 1954; and the lightweight Swinger Model 20 camera in 1965. The Swinger sold for just $19.95. “The photographic trade and technical press appreciated the rapid evolution of Polaroid’s products over a relatively short period of time,” Ronald K. Fierstein writes in A Triumph of Genius, “recognizing the commitment of the company to the technology it was pioneering.”(19)

Victor McElheny, personal communication with Melissa Banta, June 21, 2024. See also Victor K. McElheny, “Black and White: Morse,” in Insisting on the Impossible: The Life of Edwin Land (Reading, Mass.: Perseus Books, 1998), 203–219.

“Polaroid-Land Process Now Has Black and White,” U.S. Camera (August 1950), 42. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.232, Folder 21.

Arthur Juntunen, “Land Camera Gets Black-White Film,” The Detroit Free Press (May 11, 1950). Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.96, Press Clippings, Black and White Film, 1950, Folder 1.

Peter C. Wensberg, Land’s Polaroid: A Company and the Man Who Invented It (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1987), 128.

William J. McCune, Oral History Project, Interviews with William J. McCune, Chairman, Polaroid Corporation, June–August 1990, 114. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.28, Folder 2.

Inge Reethof, Interview, 3, M. Morse Project Interviews, 1993. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.5, Folder 32.

Eudoxia Muller Woodward, “Notes for Tape for Land Memorial at Hynes Auditorium, Boston, 1991.” Eudoxia Woodward Family Collection.

Howard Rogers later became director of research.

Mary McCann, personal communication with Melissa Banta, July 22, 2024.

Meroë M. Morse to SX-70 Laboratory, Memo, February 11, 1957. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.10, Folder 6.

Reethof, Interview, 4.

Edwin H. Land quoted in Francis Bello, “The Magic That Made Polaroid,” Fortune (April 1959), 156. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box I.225, Folder 5.

Peter C. Wensberg, Land’s Polaroid, 128.

Meroë Morse to Edwin H. Land, August 1, 1950. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.03, Folder 12.

Meroë Morse to Edwin H. Land, July 26, 1957. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.03, Folder 13.

Meroë Morse to Edwin H. Land, February 21, 1951. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.03, Folder 12.

Meroë Morse, “Requirements for the Material to be Used in Our Print Coater,” Memo, July 2, 1952. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.18, Folder 3. By the late 1960s, black-and-white Polaroid film no longer required a coater.

Edwin H. Land, Polaroid Corporate Report, 1976, 7, 8. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, Box 1.464. In 1972, Polaroid introduced the SX-70 camera, called by Land the “absolute one-step photography.” Unlike older models that required the users to remove the print from the camera manually, the new system ejected prints automatically with no chemical residue.

Ronald K. Fierstein, A Triumph of Genius: Edwin Land, Polaroid, and the Kodak Patent War (Chicago: American Bar Association, 2015), 71.