Artist Support

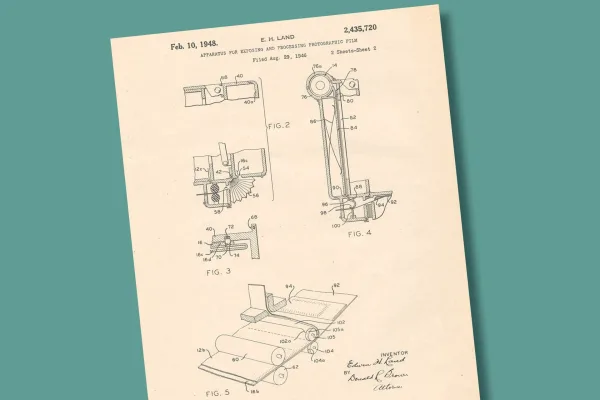

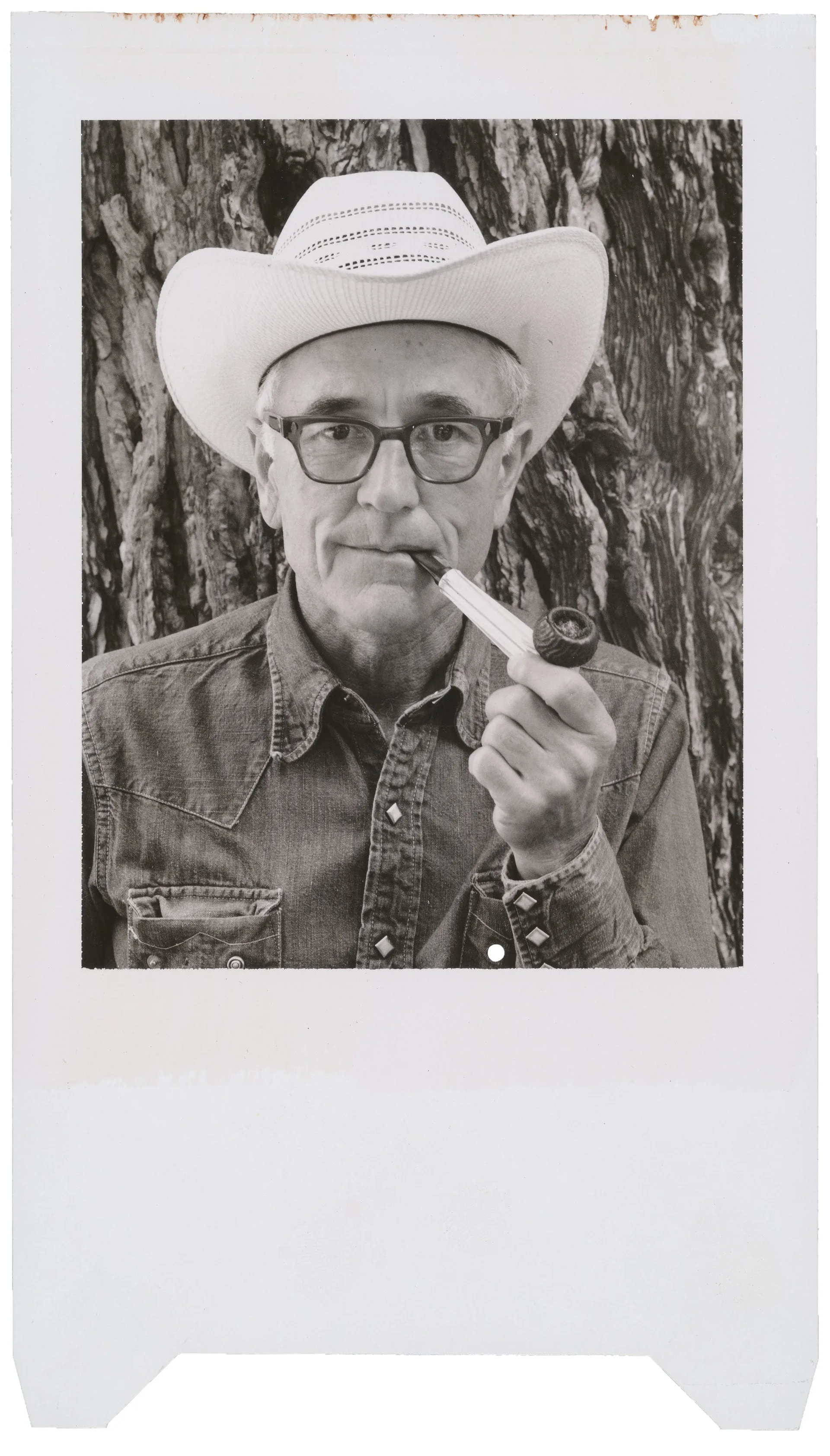

Photo: Ansel Adams and Gerry Sharpe, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1958, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, b. IX.42, f. 4.

Meroë Morse served as Polaroid’s liaison with Ansel Adams and with the other consulting photographers who provided technical advice about Polaroid cameras and films. They included Paul Caponigro, William Clift, Marie Cosindas (an early experimenter with Polaroid color film), Nicholas Dean, Gerry Sharpe, Brett Weston, Ann Bell Robb, Laurie Seamans, and others. Robb and Seamans had initially worked for Morse in her research laboratory.

Morse also advanced a program to provide Polaroid film and equipment to emerging and established artists whose work pushed the technical and aesthetic boundaries of the medium. This pioneering effort became formally known as the Artist Support Program. Barbara Hitchcock notes that “Morse defined the way in which the collection would obtain photographs—the Artist Support Program—and the kinds of technical information sought. This idea was unique, in that a commercial photography company would provide free cameras and film to photographers, who would then utilize the equipment and submit the resulting photographs to a newly formed Collections Committee.”(1)

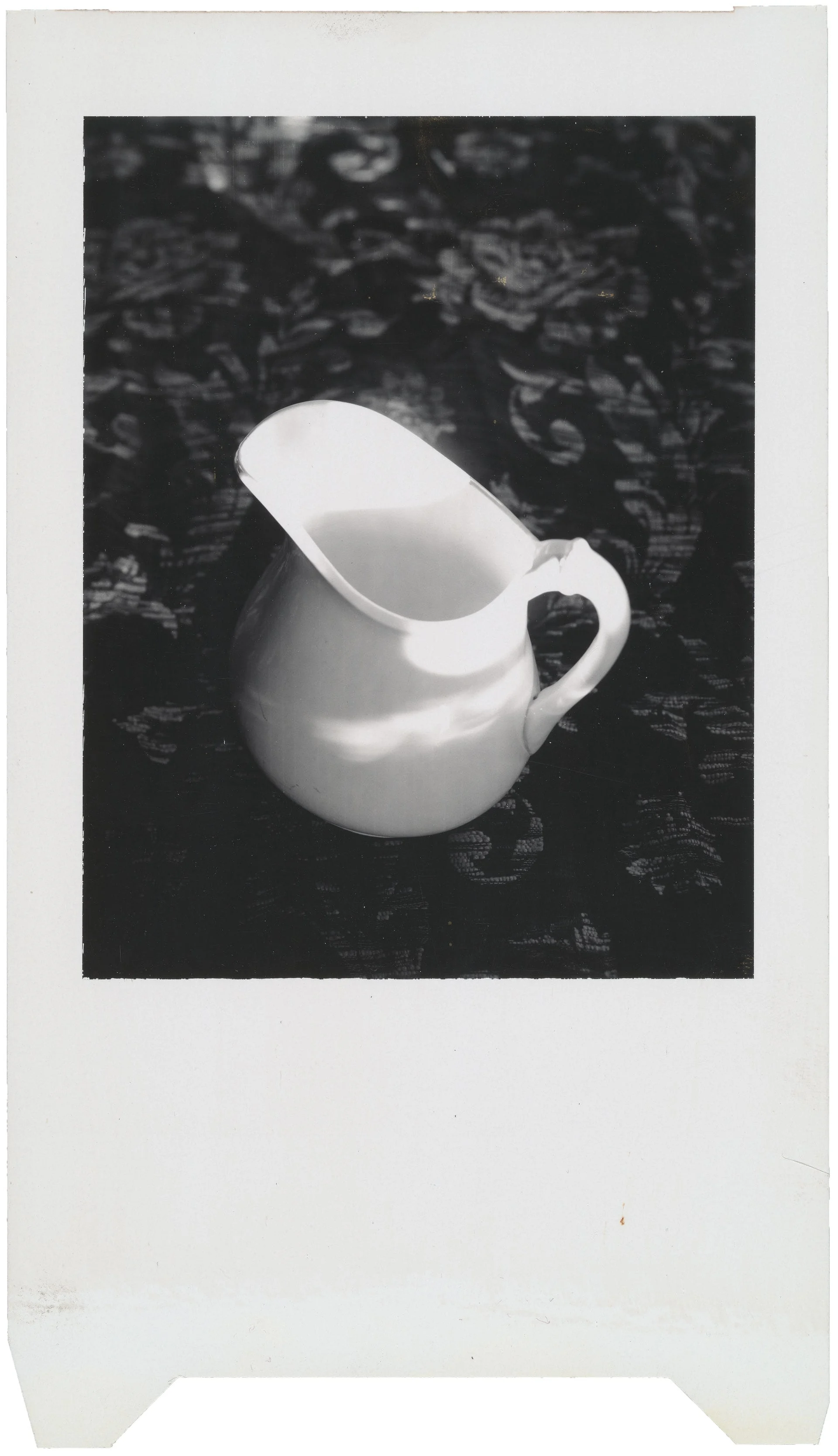

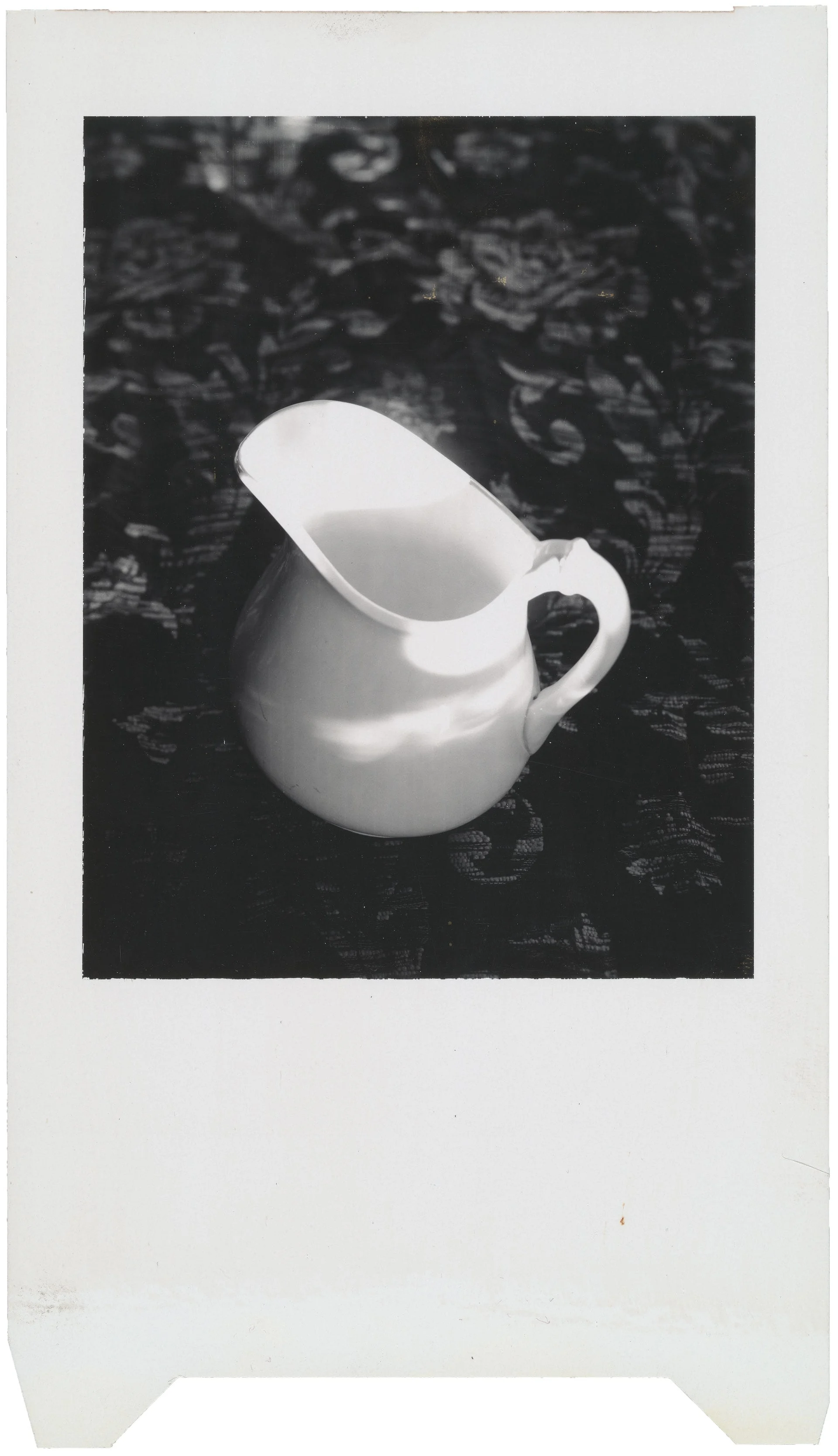

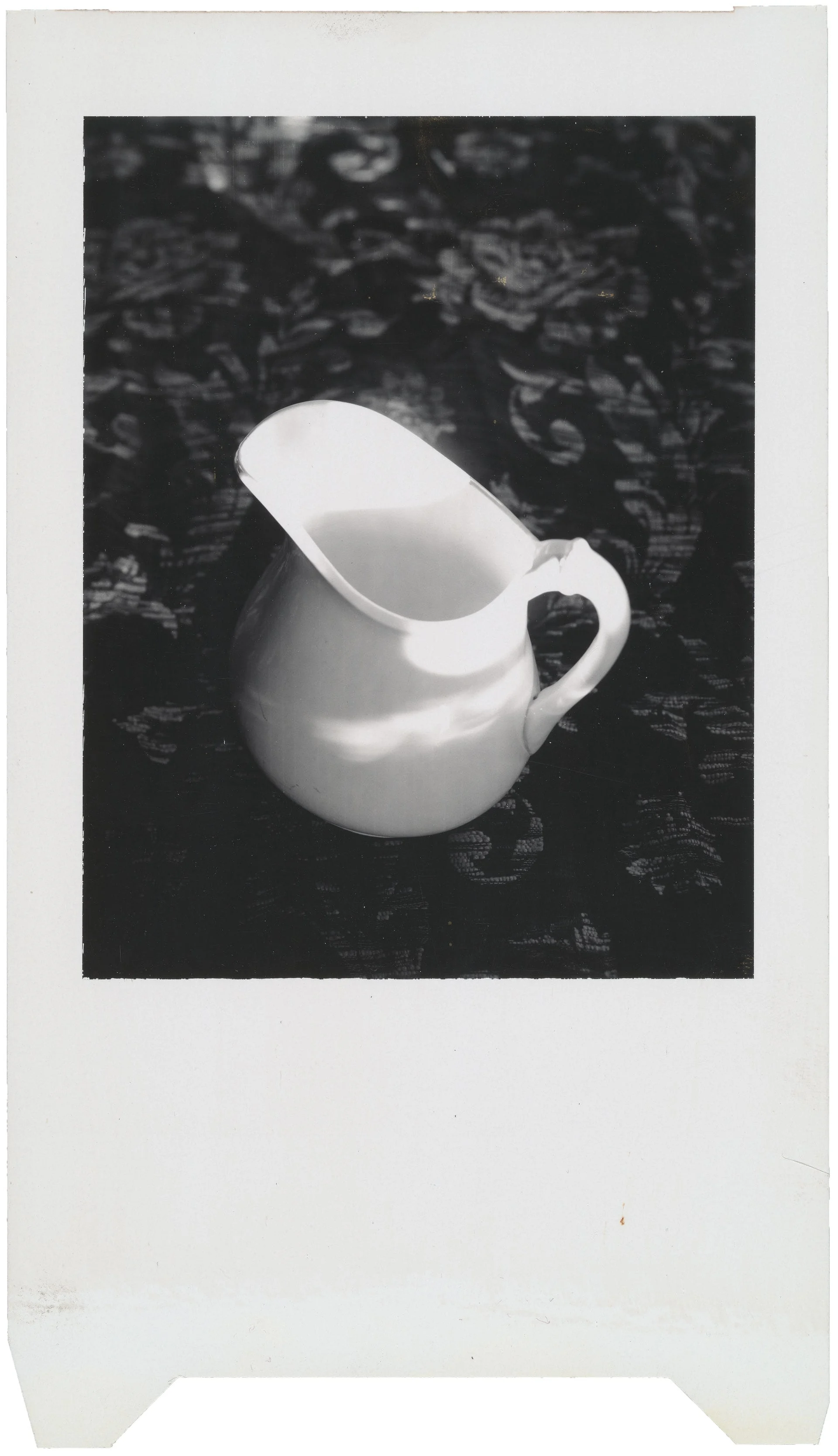

Water pitcher, test photograph by Paul Caponigro, Type 55 P/N, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.1, f. 4.

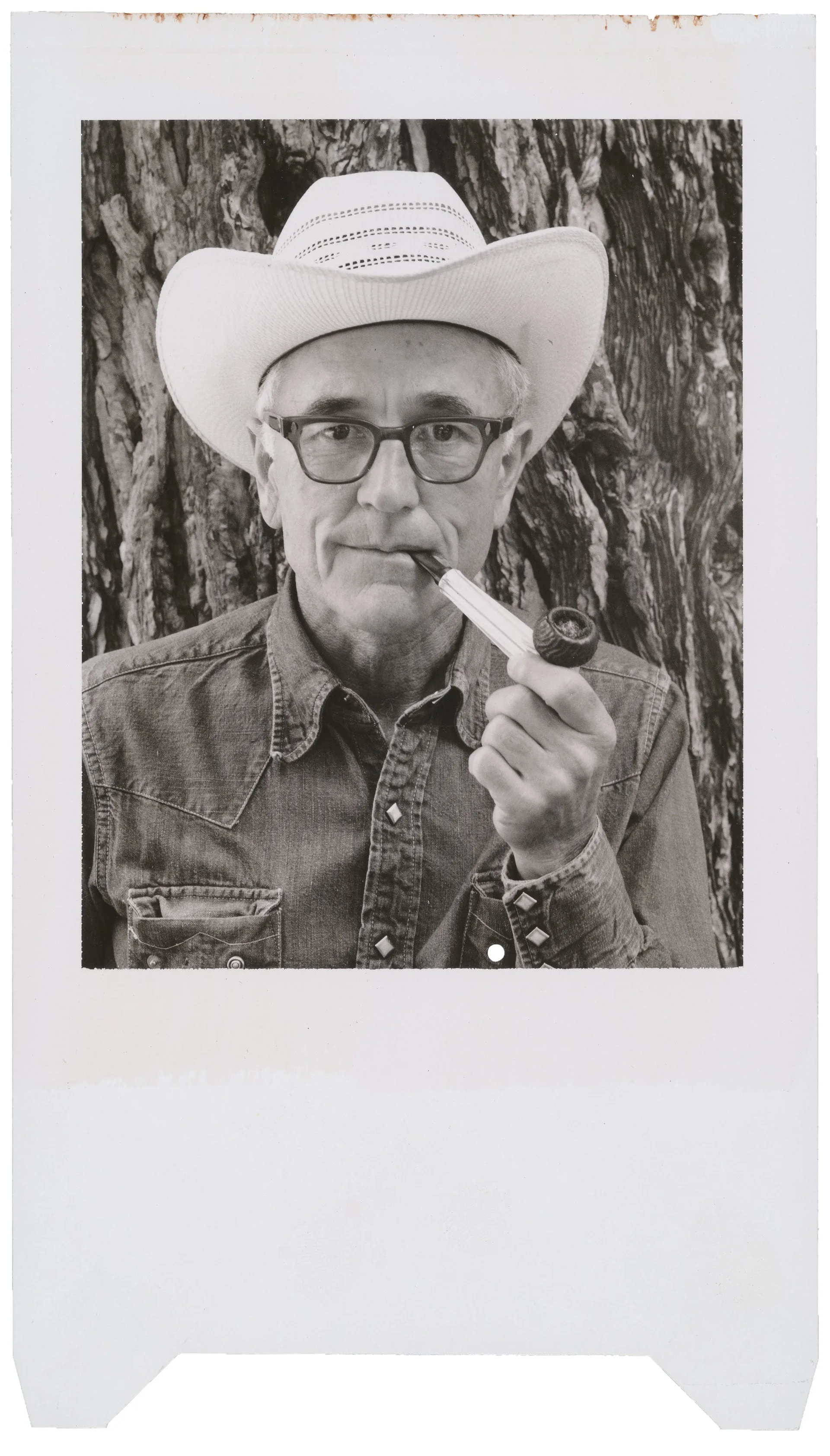

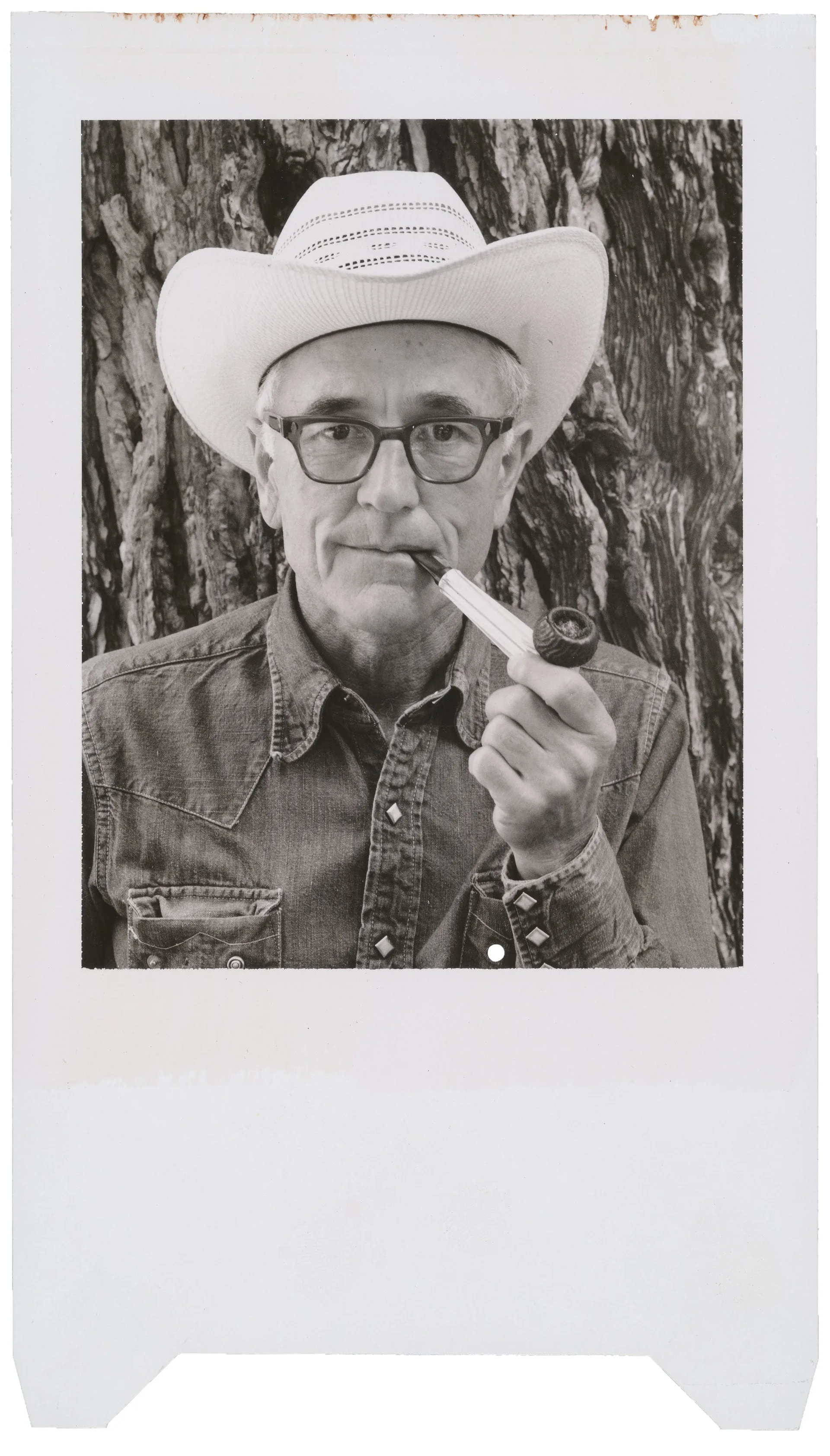

Cedric Wright, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.49, f. 5.

Julia Orynski with sculpture on windowsill, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1950, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.50, f. 11.

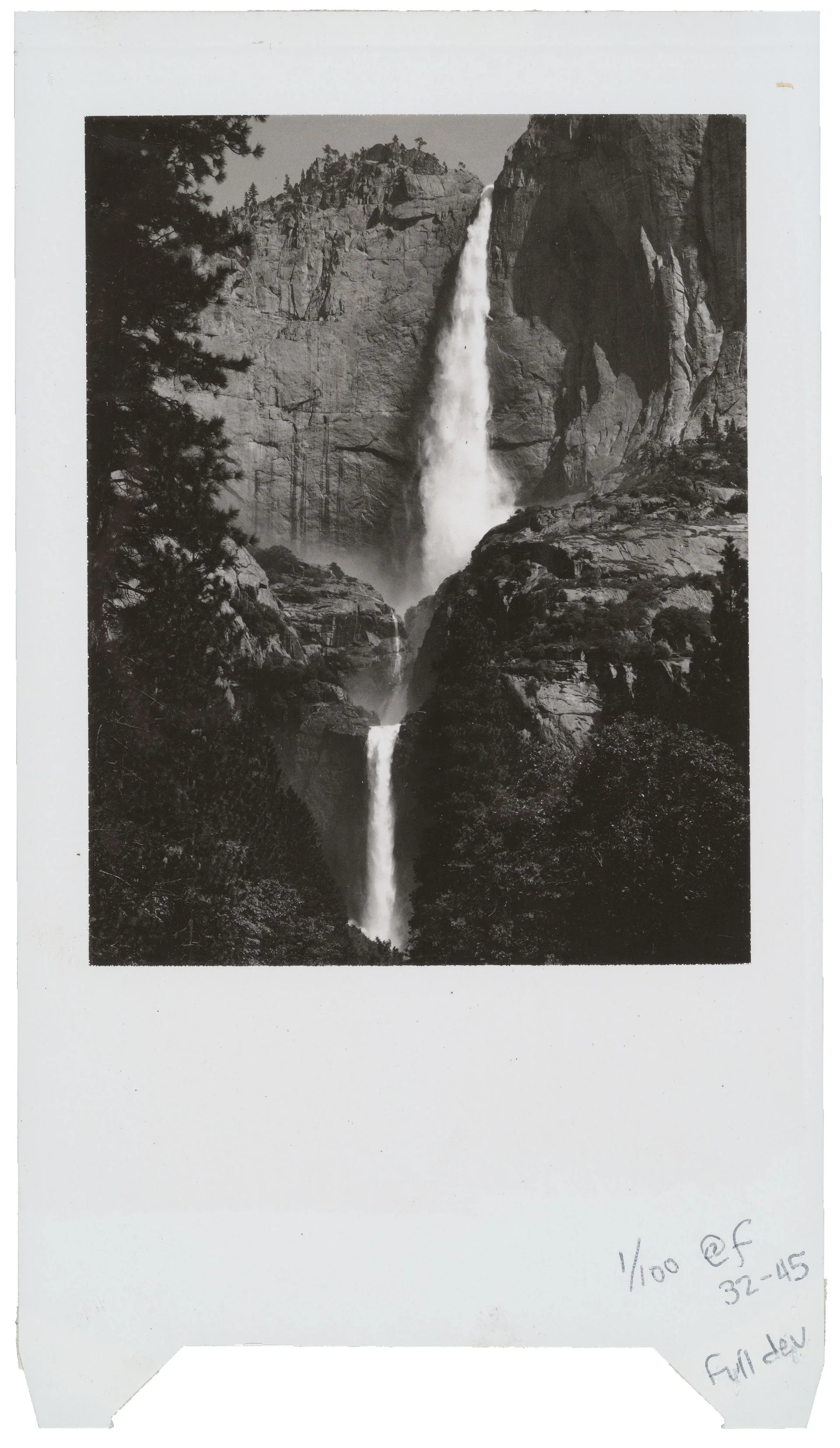

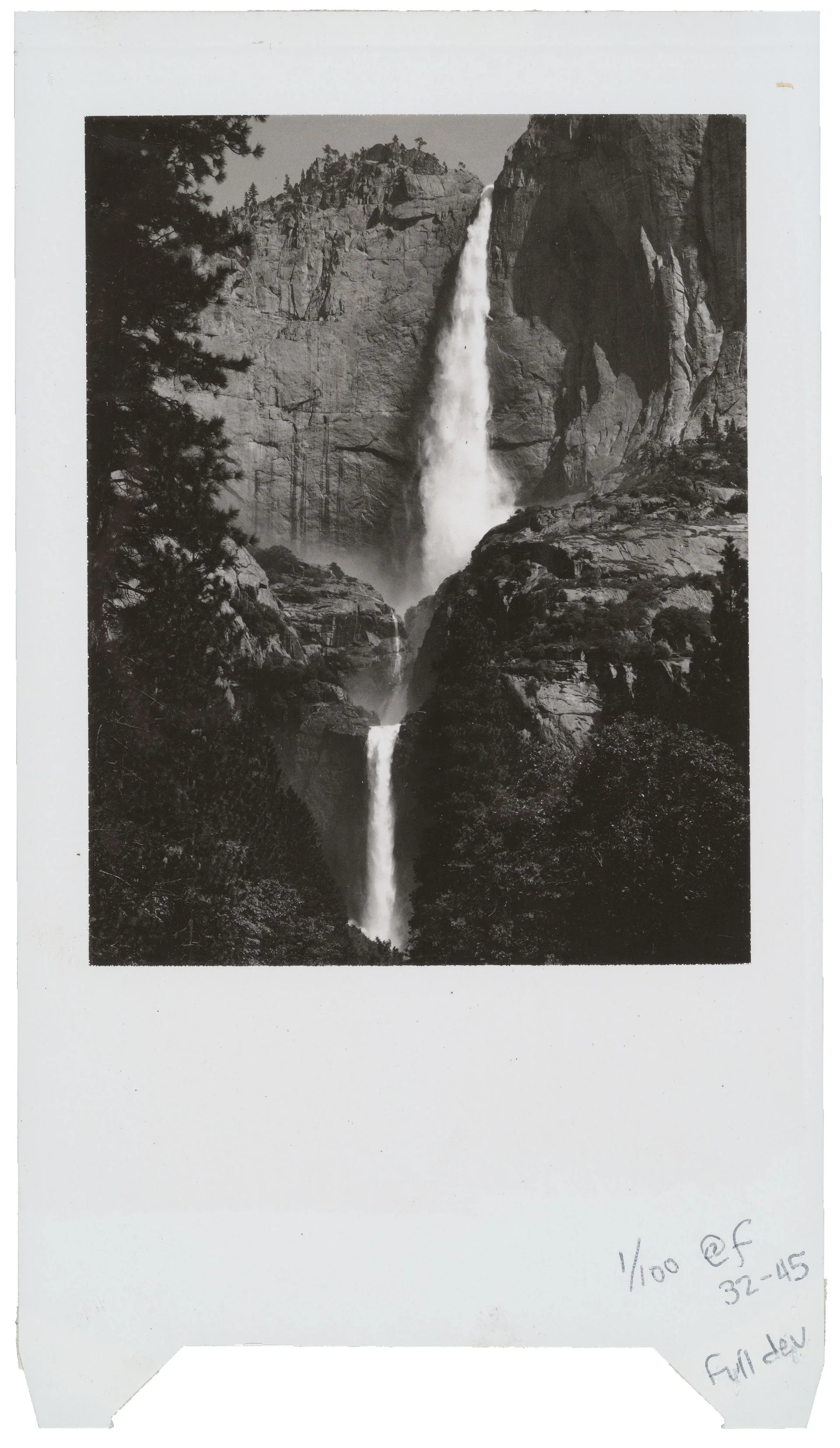

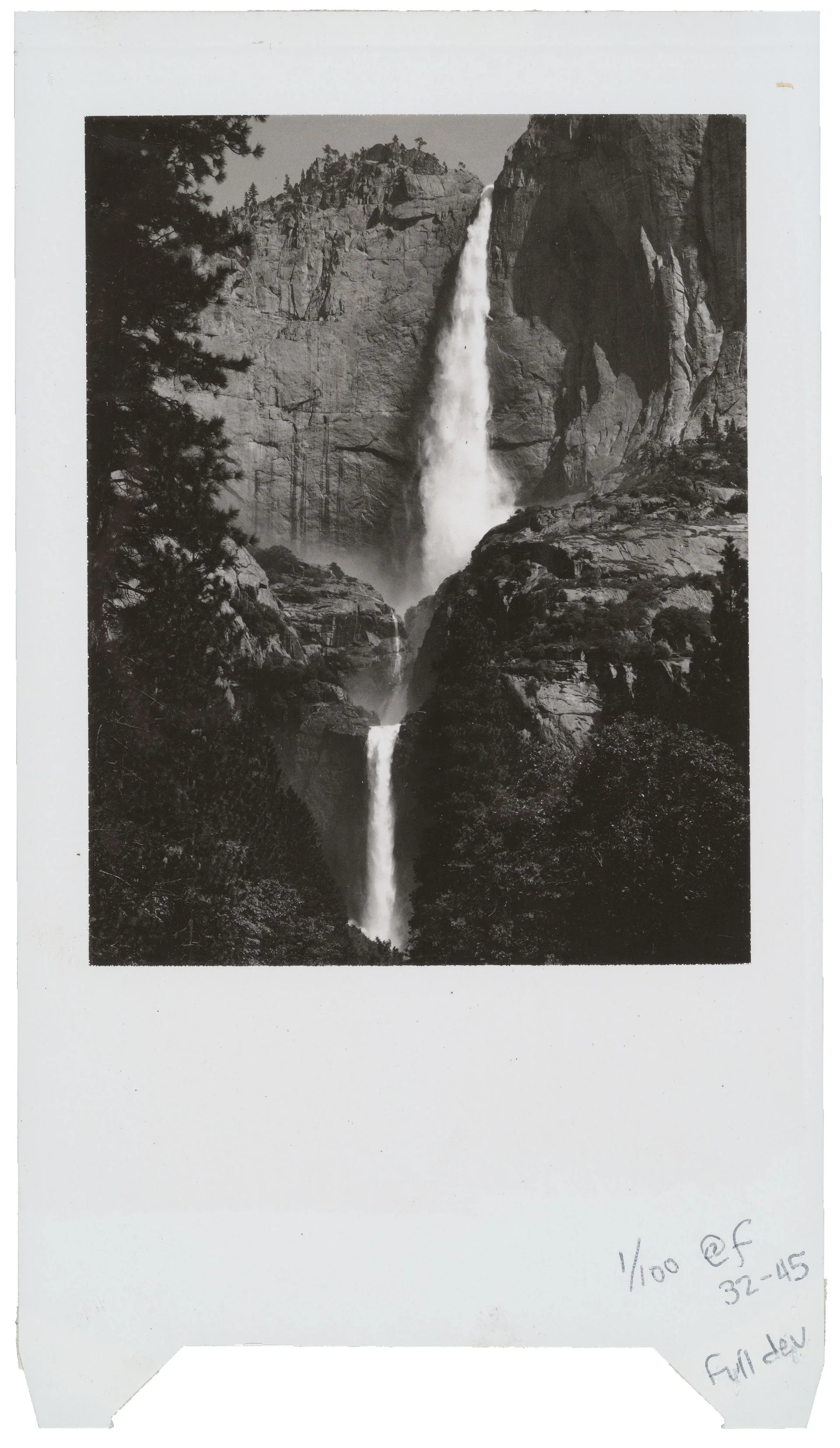

Yosemite/High Sierra: Yosemite Falls, test photograph by Ansel Adams, Type 52, 1966, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.52, f. 17.

Cedric Wright, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.49, f. 5.

Julia Orynski with sculpture on windowsill, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1950, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.50, f. 11.

Yosemite/High Sierra: Yosemite Falls, test photograph by Ansel Adams, Type 52, 1966, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.52, f. 17.

Water pitcher, test photograph by Paul Caponigro, Type 55 P/N, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.1, f. 4.

Julia Orynski with sculpture on windowsill, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1950, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.50, f. 11.

Yosemite/High Sierra: Yosemite Falls, test photograph by Ansel Adams, Type 52, 1966, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.52, f. 17.

Water pitcher, test photograph by Paul Caponigro, Type 55 P/N, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.1, f. 4.

Cedric Wright, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.49, f. 5.

In a memo to Morse and others at Polaroid dated October 15, 1962, Adams outlined the components of what became known as the Polaroid Collection, a photographic archive that came to include images from Polaroid consultant photographers and those in the Artist Support Program.(2) Adams also advocated for including “the finest examples of creative photography in all photographic media” by established artists as a way of comparing and elevating the significance of Polaroid images.(3) Photographs in other media that Adams obtained for the collection included works by Margaret Bourke-White, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, Eliot Porter, Aaron Siskind, Edward Weston, and Minor White. Morse initially oversaw the Polaroid Collection with an appointed committee and discussed plans for a gallery to exhibit the collection. “The Polaroid Collection was a reflection of the heart and soul of the company behind it,” Hitchcock writes, and it “document[ed] cultural shifts and innovative ideas through art, as presciently envisioned by Meroë Morse.”(4)

Years of discussion about the cultural significance of instant photography among Morse, Adams, Kennedy, and Land came full circle in 1973 when Polaroid opened the Clarence Kennedy Gallery to house and exhibit the Polaroid Collection. The gallery was named in honor of Kennedy, who had died the year before. It was Kennedy who asserted early on that “great” Polaroid prints should be sold and distributed as works of art.(5) Adams similarly valued the Polaroid image as a cultural and historic object: “Do not depreciate the importance of the snapshot,” he wrote. “While to many it is the symbol of thoughtlessness and chance, it is a flash of recognition. . . . It represents something seen; it may have real human and historic value.”(6)

Do not depreciate the importance of the snapshot. While to many it is the symbol of thoughtlessness and chance, it is a flash of recognition. . . . It represents something seen; it may have real human and historic value.

Ansel Adams

The intersection of photography and art at Polaroid reflected changing attitudes toward photography within the broader academic and museum community. In his discussions with Kennedy, Land advocated for the history of photography having a greater presence within the history of art curriculum at Smith.(7) Another contributor to the debate was photography historian Beaumont Newhall, a friend and colleague of Land and Morse, who gave lectures at Polaroid to company employees and wrote frequently about the creative potential of Polaroid images.(8) Newhall, whose influential book The History of Photography, published in 1937, advanced the history of photography as a field of study, became the first curator of photography at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) and later curator of the George Eastman House. Adams had helped establish the department of photography at MoMA in 1940 and at the San Francisco Art Institute in 1946.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, increasing support for photography as an artform in Boston and across the country brought about changing perceptions of photographs as both artistic and cultural primary source materials: photographs assumed a greater presence in museums; cultural and academic institutions began to recognize the value of their photographic holdings; and photographs increasingly appeared in the art market.(9) The educational programs, exhibitions, and interdisciplinary exchange actively championed by Polaroid contributed in impactful ways to the acceptance of photography as a fine art form and to the emerging discipline of the history of photography.

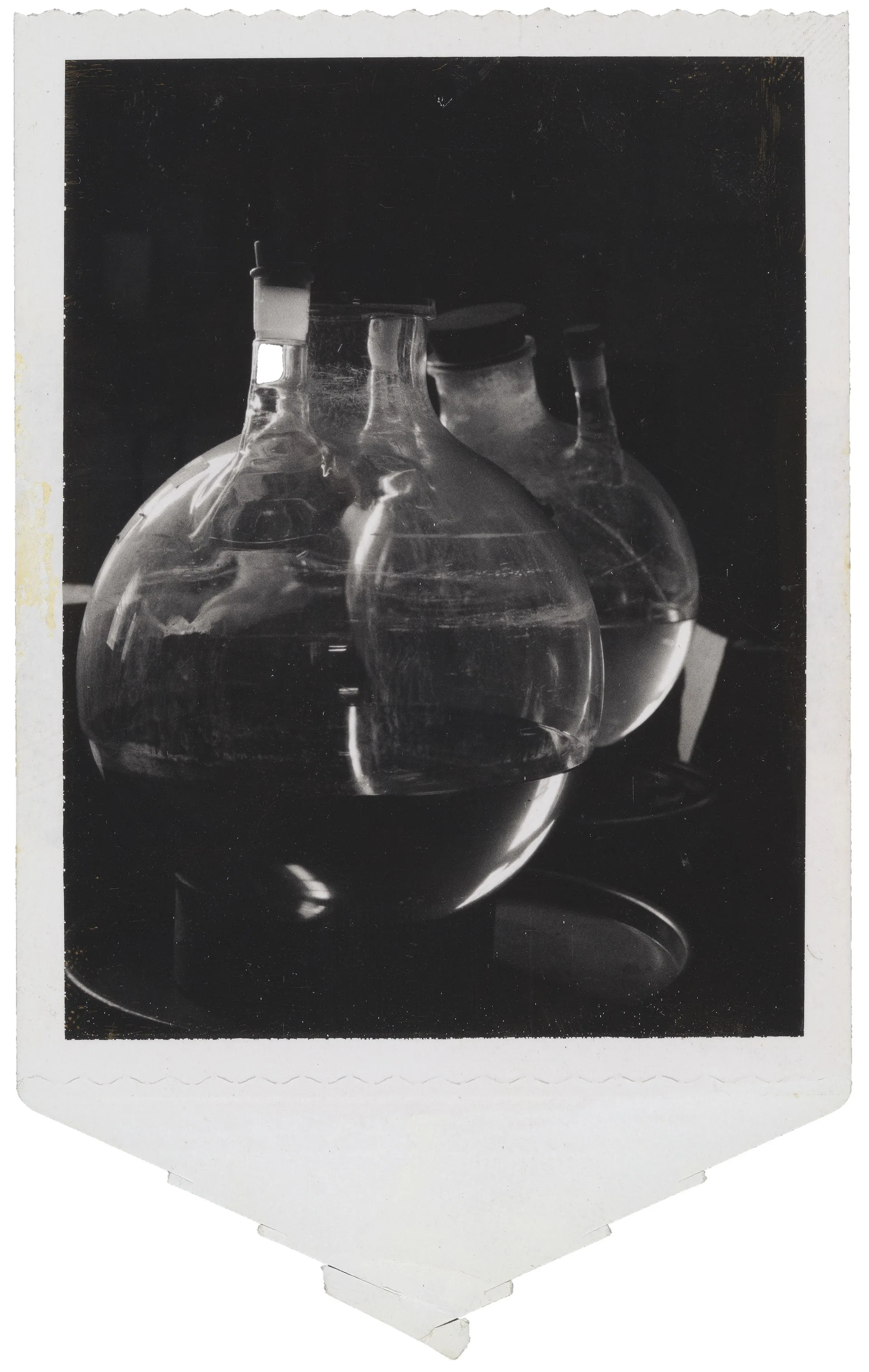

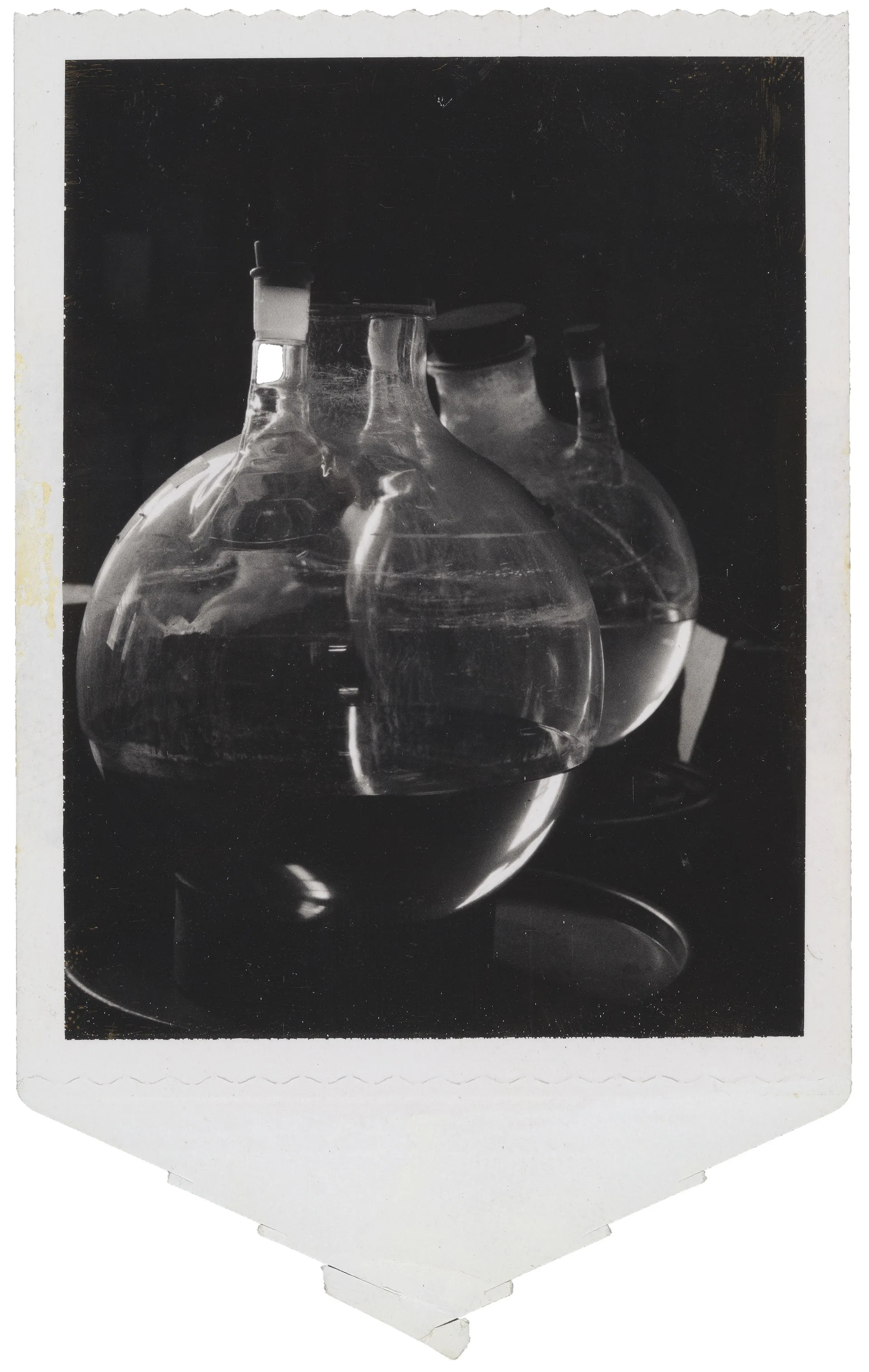

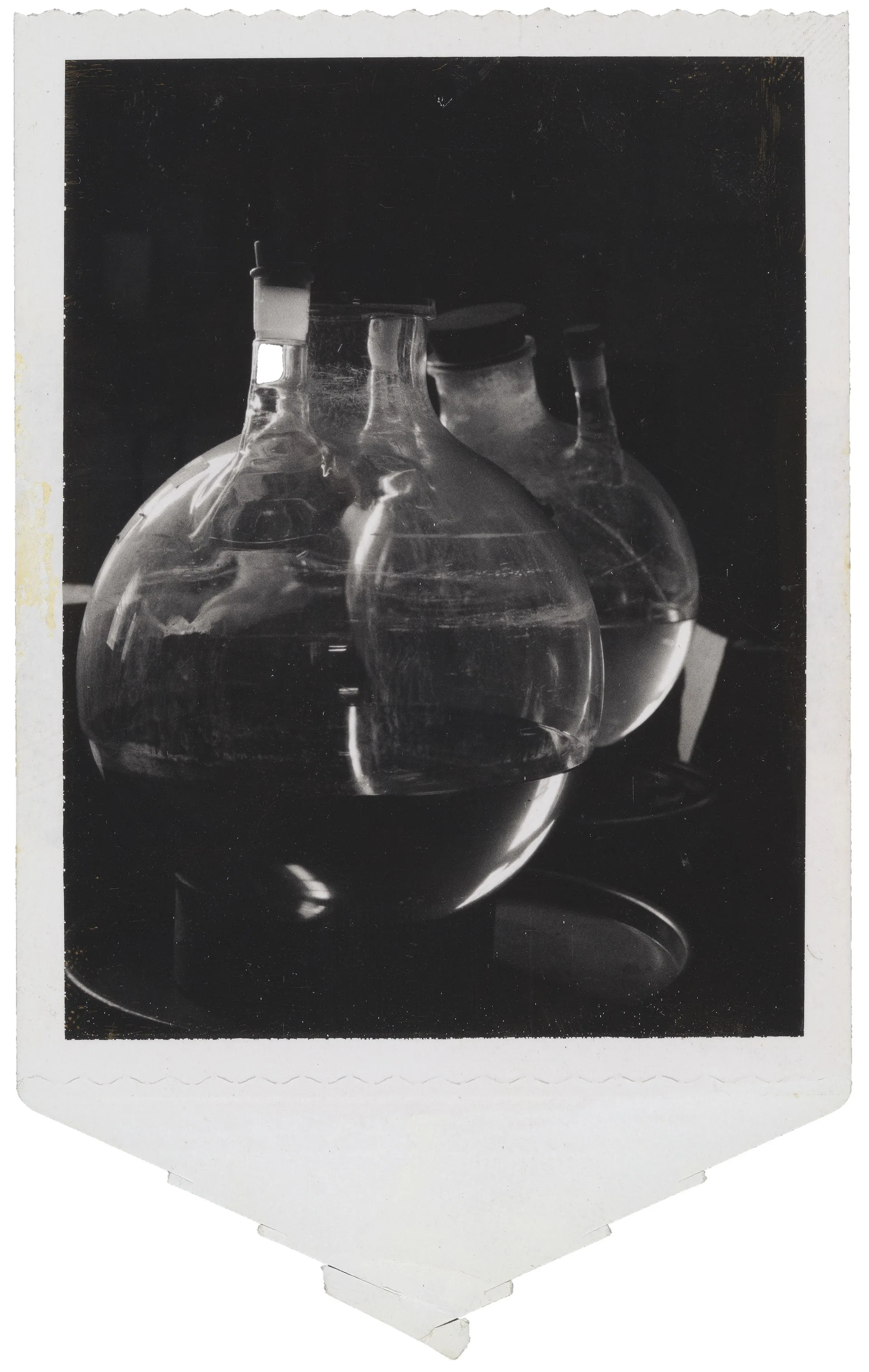

Bottles, test photograph by Nicholas Dean, Type 47, ca. 1961. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5. f. 17.

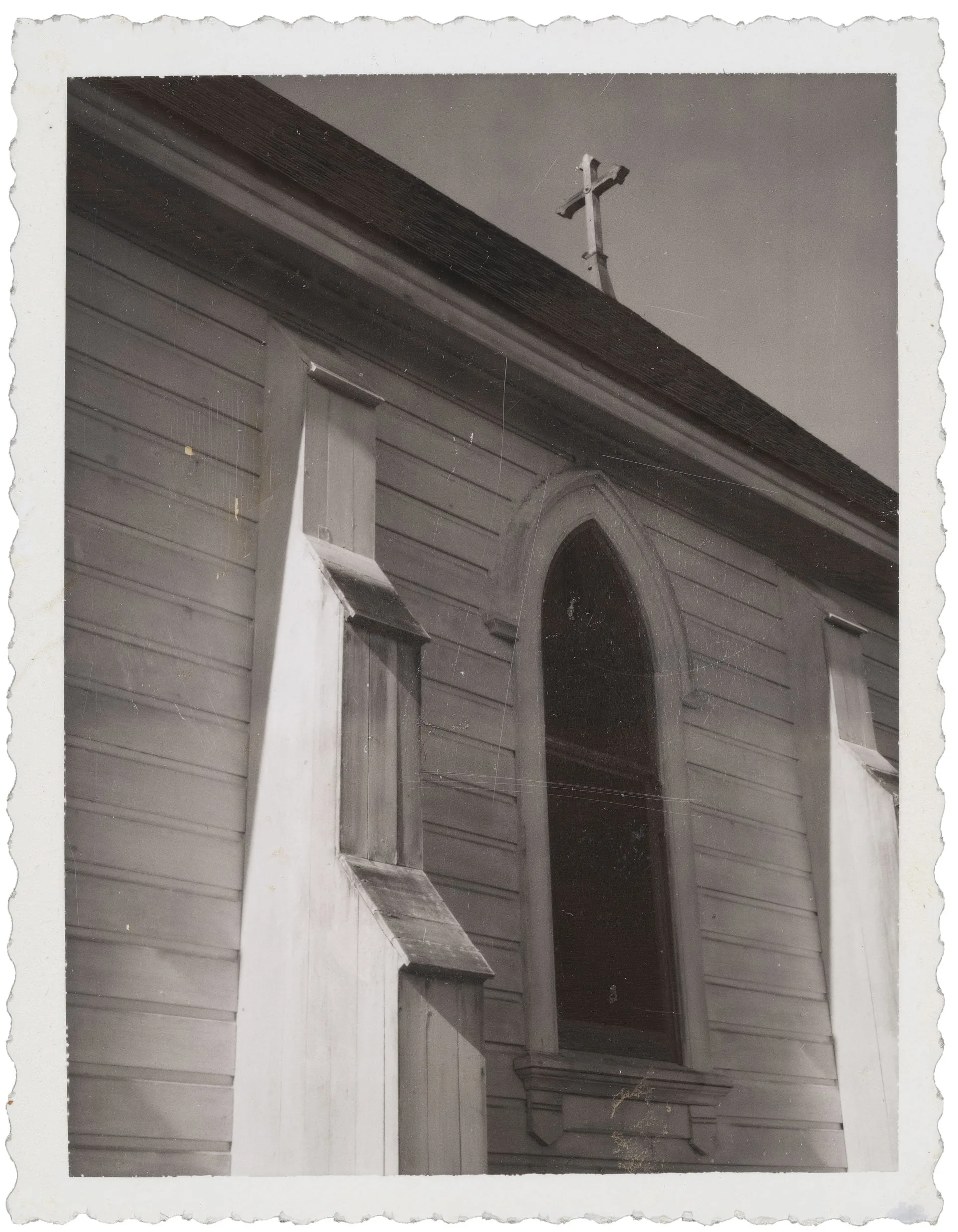

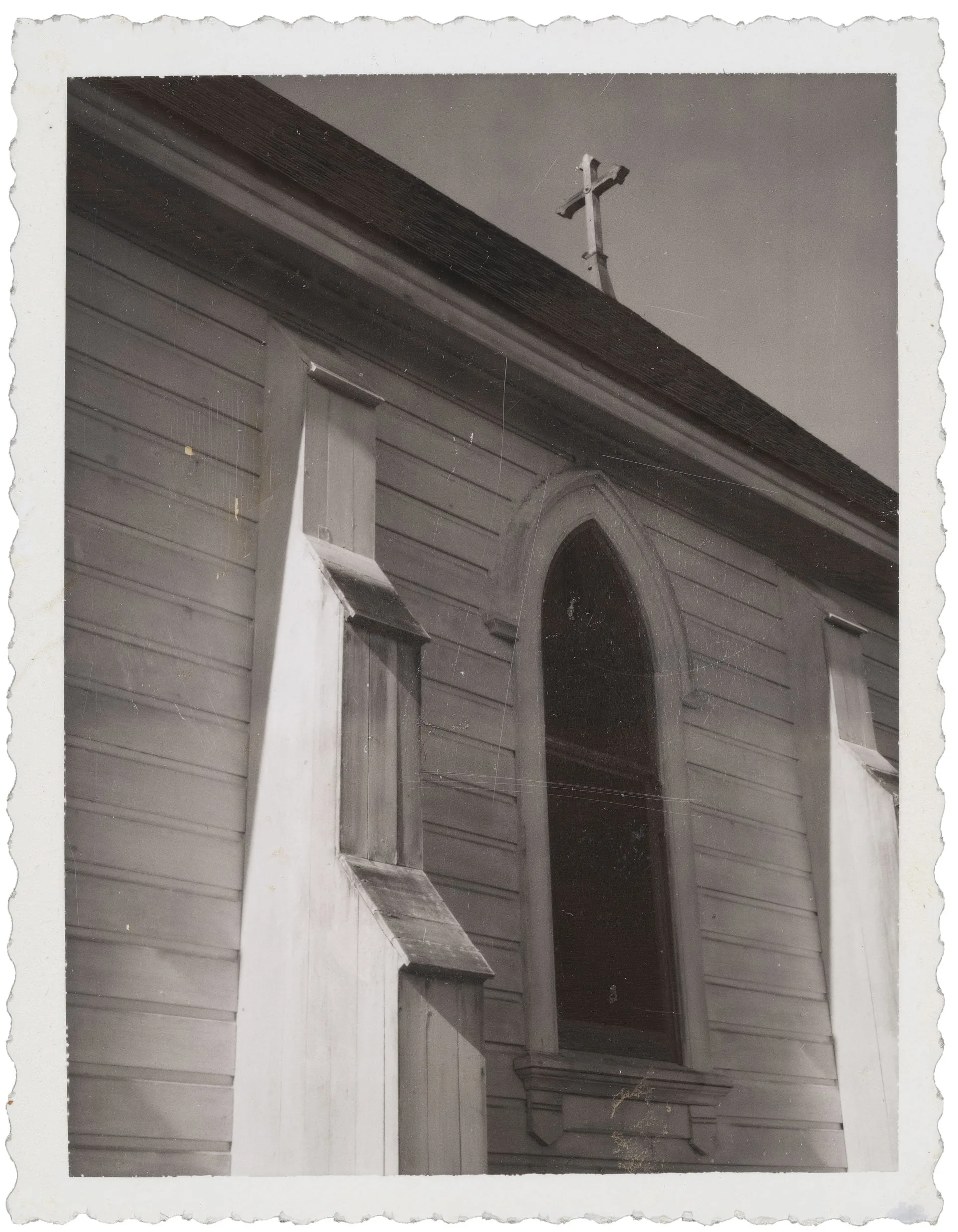

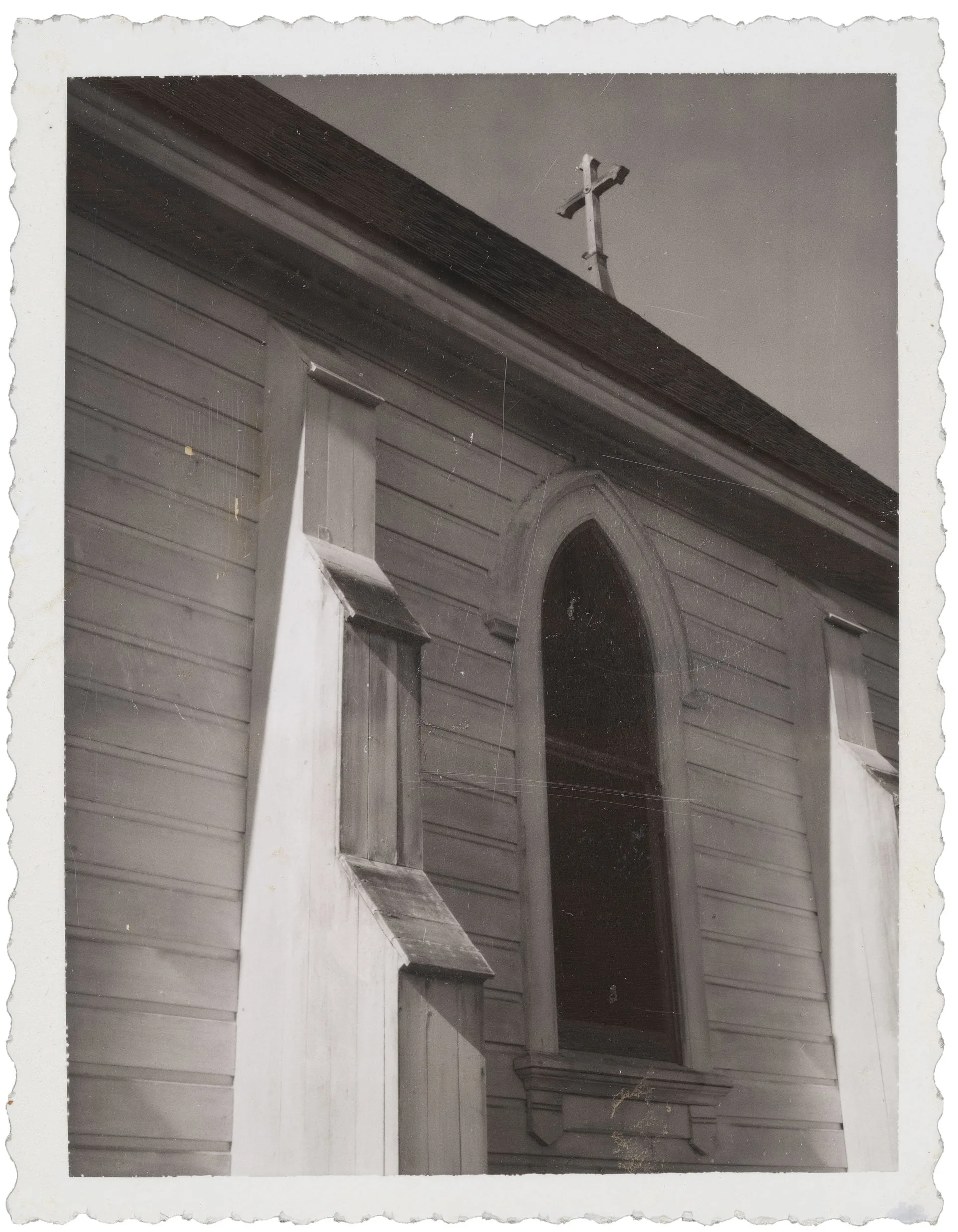

Church, test photograph by Gerry Sharpe, Type 41, ca. 1955. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5, f. 31.

Still life, test photograph by Marie Cosindas, ca. 1972. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 11.

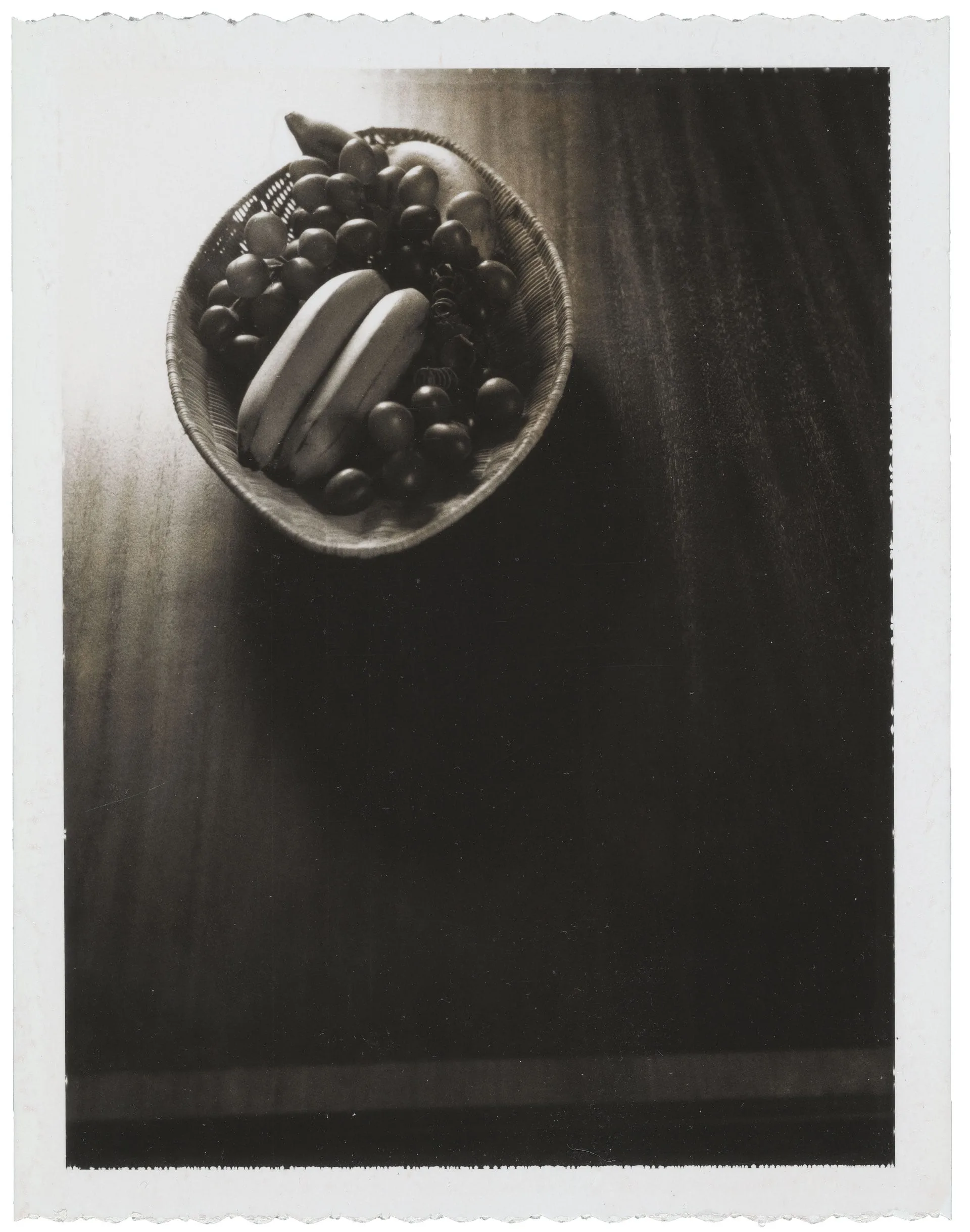

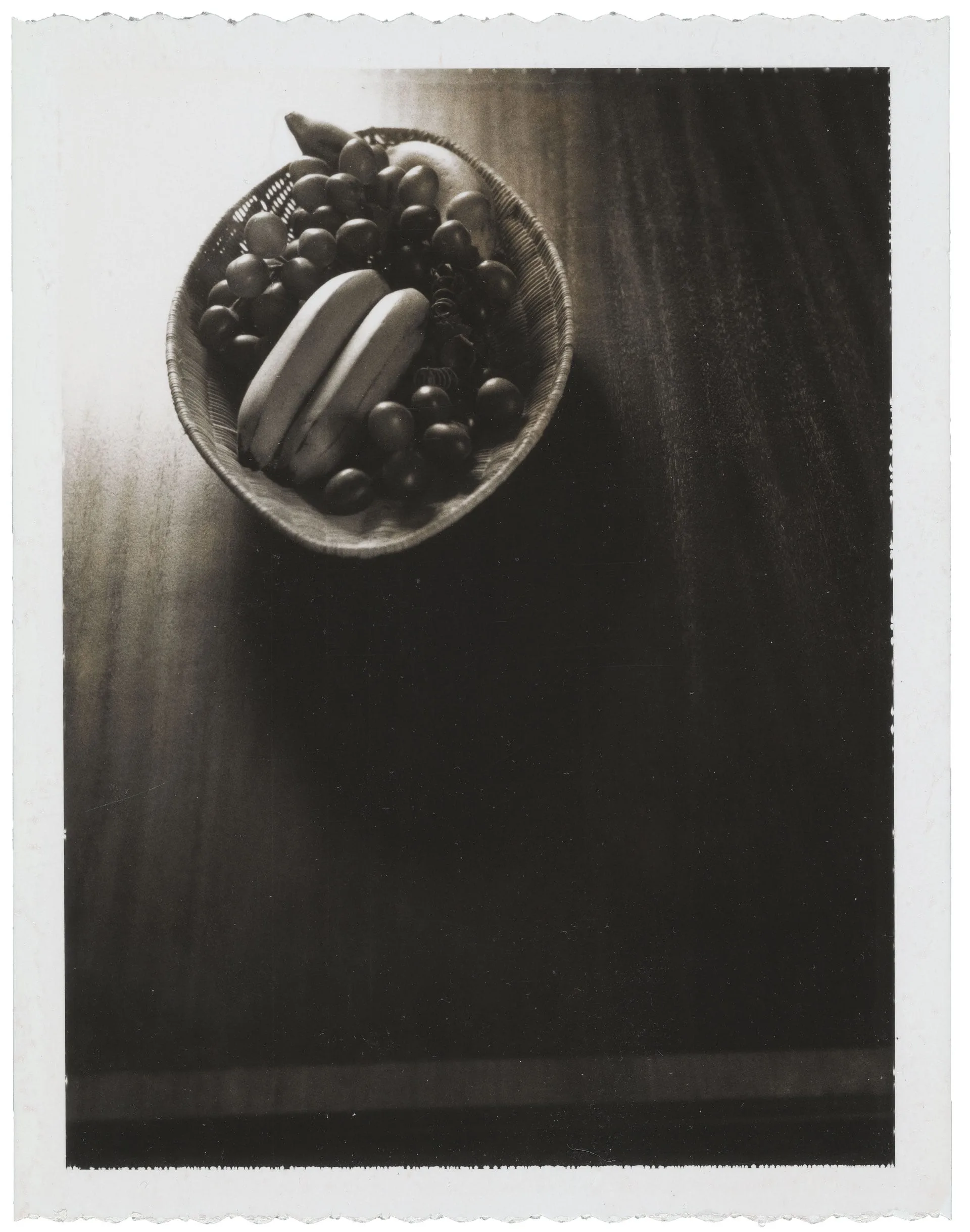

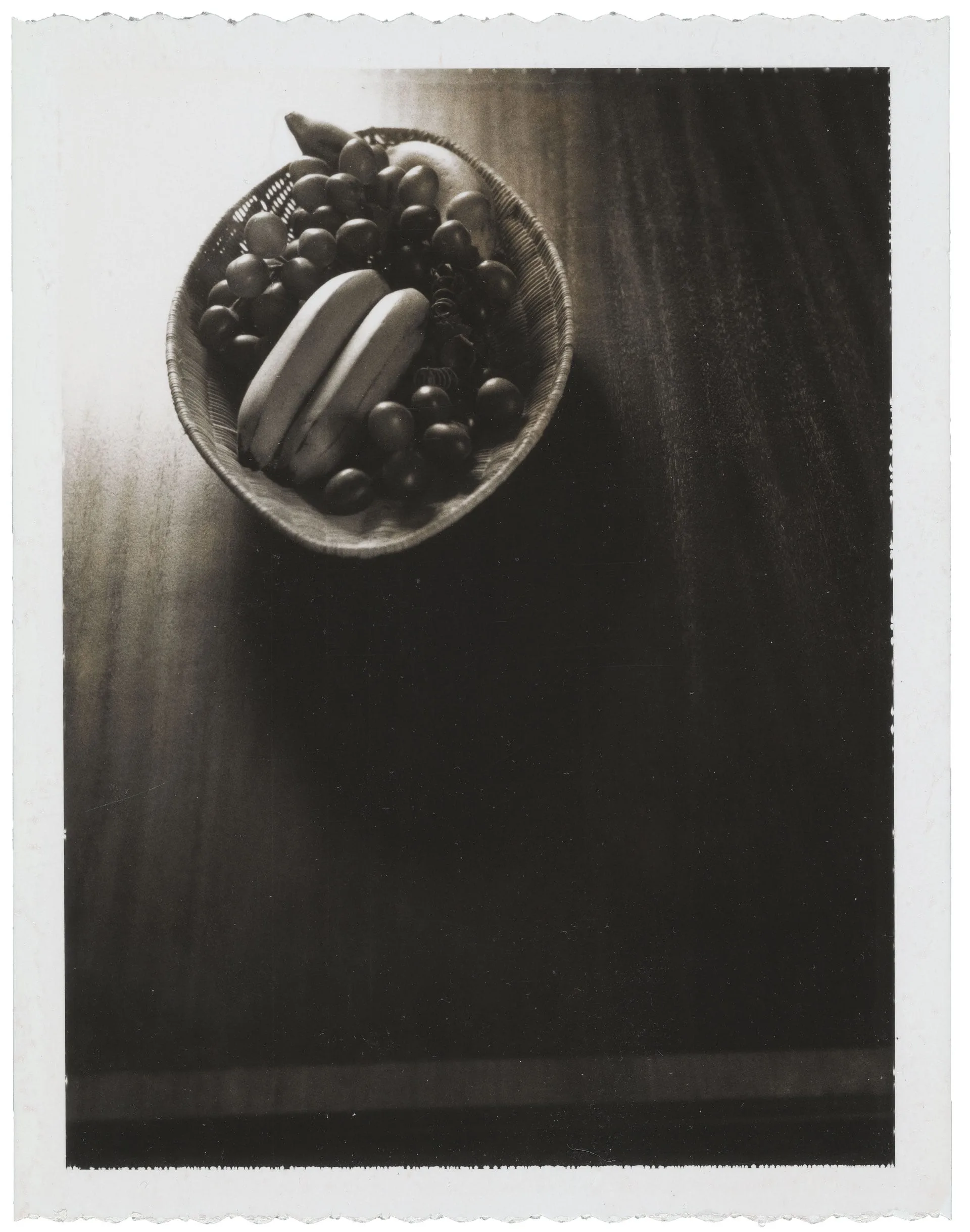

Fruit, test photograph by Ann Bell Robb, May 2, 1960. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 8.

Church, test photograph by Gerry Sharpe, Type 41, ca. 1955. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5, f. 31.

Still life, test photograph by Marie Cosindas, ca. 1972. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 11.

Fruit, test photograph by Ann Bell Robb, May 2, 1960. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 8.

Bottles, test photograph by Nicholas Dean, Type 47, ca. 1961. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5. f. 17.

Still life, test photograph by Marie Cosindas, ca. 1972. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 11.

Fruit, test photograph by Ann Bell Robb, May 2, 1960. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.8, f. 8.

Bottles, test photograph by Nicholas Dean, Type 47, ca. 1961. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5. f. 17.

Church, test photograph by Gerry Sharpe, Type 41, ca. 1955. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs of Polaroid Consultant Photographers, b. XI.5, f. 31.

Barbara Hitchcock, “Remembering a Grand Experiment: A Personal History of the Polaroid Collection,” in Rebekka Reuter, William A. Ewing, Barbara Hitchcock, Deborah G. Douglas, Gary Van Zante, Christopher Bonanos, Peter Buse, Dennis Jelonnek, John Rohrbach, and Amon Carter Museum of American Art, The Polaroid Project: At the Intersection of Art and Technology (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 96–97.

Ansel Adams to E. H. Land, M. M. Morse, J. Sykes, Nick Dean, “Subject: Print Collection,” October 15, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs and Correspondence of Polaroid Consultant Photographer Ansel Adams, Box IV.1, Folder 26.

Ibid. See also Hitchcock, “When Land Met Adams,” 26.

Hitchcock, “Remembering a Grand Experiment,” 97, 102.

Margaretta Kuhlthau, “Thoughts on Photography as Art,” Memo, November 5, 1957. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.02, Folder 10.

Ansel Adams, Polaroid Land Photography (Boston: New York Graphic Society, 1963), x.

Kuhlthau, “Thoughts on Photography as Art,” 1.

Beaumont Newhall also encouraged other fine art photographers to engage with the Polaroid process. See Polaroid Newsletter, September 26, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box I.522, Folder 37.

See Kim Sichel, “Photography in Boston, 1955–1970: Science and Mysticism,” in Rachel Rosenfield Lafo, Gillian Nagler, and DeCordova Museum Sculpture Park, Photography in Boston, 1955–1985 (Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 2000), 3–25.