Ansel Adams and Polaroid R&D

Photo: Ansel Adams with Polaroid camera, ca. 1972. “The Polaroid Newsletter for Photograph Education,” Volume IV, No. 2, Spring 1987. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.38, Folder 8.

It was Clarence Kennedy who in 1948 introduced Land to the photographer Ansel Adams. Adams remembered, “I responded warmly to Land’s intellect and personality; we seemed to intuitively understand each other.”(1) After purchasing one of the photographer’s print portfolios, Land wrote to Adams, “My own admiration for your combination of aesthetic and technical competence is complete. . . . I should like to send you a camera and associated equipment and film as a personal gift.”(2)

Land asked Adams to serve as a consultant to test Polaroid cameras and films. Assessment of the performance and functionality of Polaroid products represented a key stage in the company’s research and development. Meroë Morse played a significant role in this effort as company liaison to Adams, who systematically reviewed technical and design aspects of Polaroid prototypes, from the wording of instruction manuals to the tonal values of finished prints.(3) Early on, for example, Adams observed the limited tonal range of the sepia prints from Type 40 film, the first Polaroid instant photography film, introduced in 1948. As her laboratory worked tirelessly throughout the 1950s and ’60s on the advancement of black-and-white films, Morse valued the observations made by Adams, who was known for the technical and artistic quality of his images and for his masterful printing.

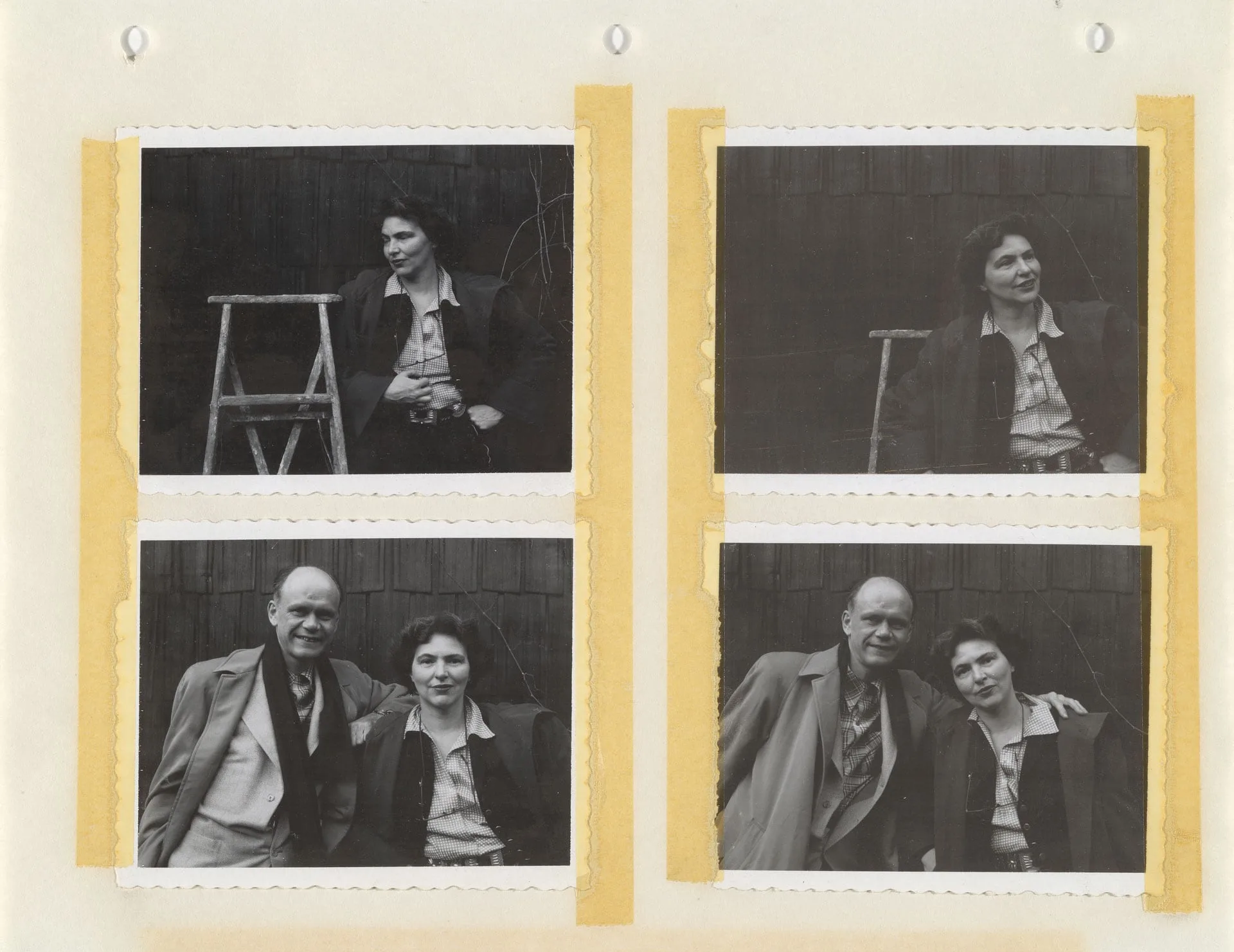

Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, test photographs by Ansel Adams, January 1954, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.2, f. 30.

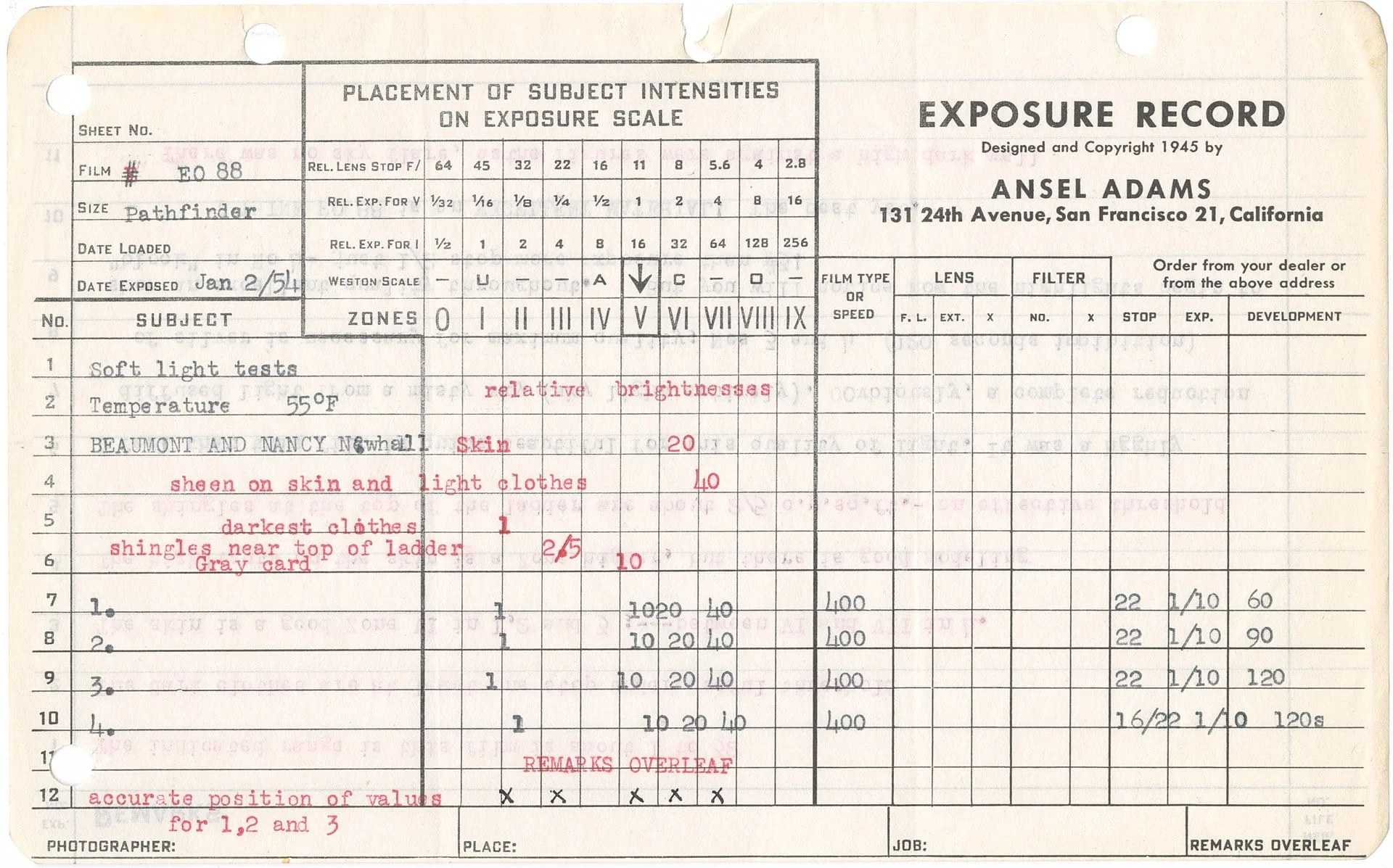

Exposure record for test photographs of Beaumont and Nancy Newhall, January 1954. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.2, f. 27.

Adams understood that Land “believed strongly that if a stable, simple, and high-quality photographic process could be universally available at reasonable cost, creative expression and communication would be enhanced on a scale heretofore considered impossible.”(4) While in his own practice Adams took an active role in all aspects of developing and printing a photograph, with Polaroid he was working on a system that would remove the user from the concerns of which he himself was a master. “Known for his technical expertise in darkroom photography and his pristine prints, Adams seemed an unlikely choice for a company whose name became synonymous with instant photography, a technology in which the print is developed inside the camera without darkroom equipment,” Jennifer Quick writes in “Designing Polaroid: Ansel Adams as Consultant.” Quick goes on to observe that “Adams’s extensive knowledge, however, was precisely what made him ideal for the job.”(5) Adams continued as a consultant at Polaroid until his death in 1984 and left behind an archive of more than 10,000 test photographs and 3,000 memos, now in the Polaroid Corporation Collection archives at Baker Library.

If a stable, simple, and high-quality photographic process could be universally available at reasonable cost, creative expression and communication would be enhanced on a scale heretofore considered impossible.

Ansel Adams

Adams enjoyed the company’s collaborative culture and shared his observations about black-and-white and new color films with other Polaroid colleagues and researchers. John McCann, a senior laboratory manager in research in human color vision, large-format color photography, digital imaging, and image reproduction, recalls Adams’s visits to Polaroid: “Ansel would make suggestions about everything new that people were working on. There were a lot of Ansel’s large prints on research walls and meeting rooms.” McCann said he could easily locate Adams at Polaroid by listening for “people laughing . . . [and finding] Ansel in the middle of the crowd.”(6)

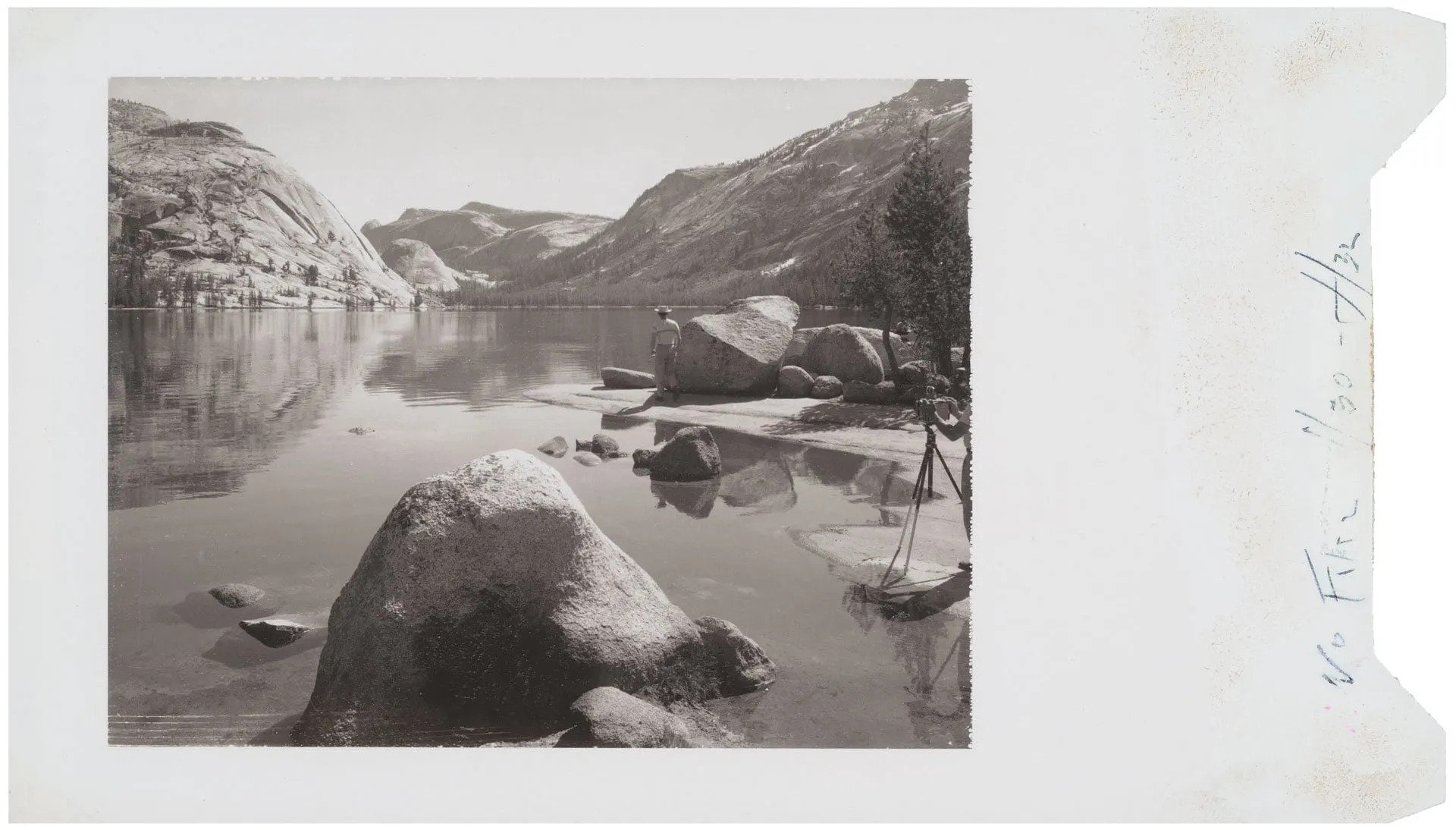

To test Polaroid cameras and films, Adams often took a series of photographs of the same subject using different aperture settings, filters, and exposures. His technical approach included the use of the Zone System, a method of calculating and adjusting the exposure and development of the film to help determine and control in advance the tonal values of a final print. He tested cameras and films indoors as well as outdoors in less controlled conditions. Land “was interested in the problems a photographer has with the technology available,” Adams explained. “The criticisms of his camera that I would give him would be very different from the kinds of criticism he got from his labs.”(7)

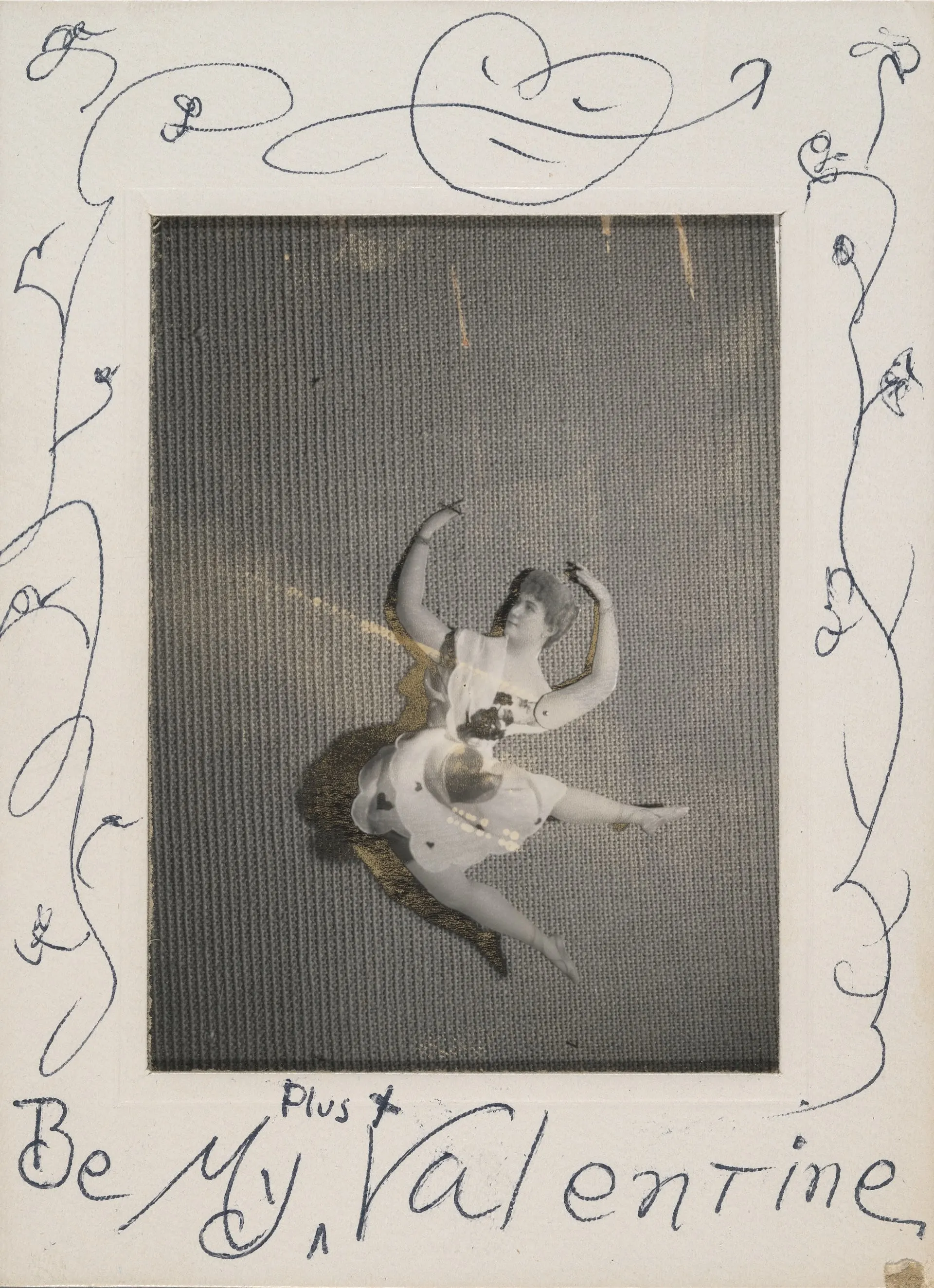

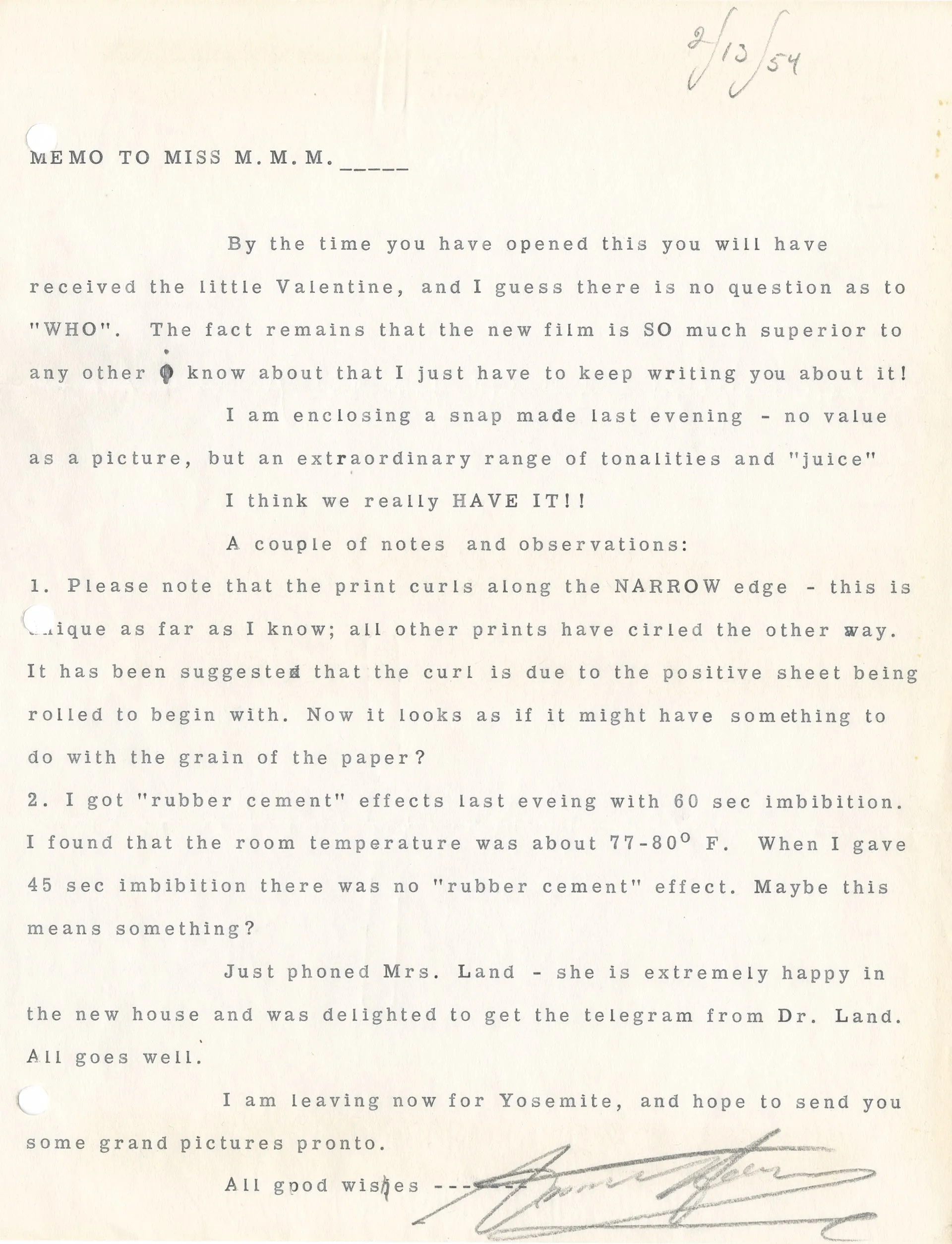

Letters between Adams and Morse express the joy and affection that characterized their technical and artistic journey together. In a whimsical memo dated February 13, 1954, Adams sent Morse a test photograph with the inscription, “Be my Plus X Valentine.” Adams was referring to Plus-X film, which, he wrote, “is SO much superior to any other i [sic] know about that I just have to keep writing you about it!”(8) In a memo dated December 1962, Adams offered observations on the density and contrast of Type 55 P/N film, which produced reusable 4×5 negatives from which multiple prints could be made. “The New 55 is remarkable in concept! A great step forward! But needs some obvious improvements.”(9) The letter begins with Adams’s confession of being “a bit woozy” after a party, noting that his “noble son hath prepared a hot toddy today which has worked wonders and the cranial computer is working OK again.”(10)

Valentine photograph, test photograph by Ansel Adams, Plus-X film, February 1954, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.2, Folder 33.

Valentine letter from Ansel Adams to Meroë Morse, February 13, 1954. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.2, Folder 32.

Kindred spirits, Morse and Adams remained devoted to discovering the technical and artistic possibilities of the new medium, believing that its ease of use would encourage amateurs to become artists and its aesthetic potential would afford artists a new means of expression. Adams’s “consulting work yielded key insights for the company and also for his own practice by giving him close proximity to cutting-edge photographic technologies and the space in which to help design them,” Quick writes.(11)

In a letter to Land dated August 10, 1950, Morse enthused that “a beautiful black + white picture came in from Ansel Adams. . . . A brief note [from Adams] came with it to say ‘The material is beautiful in quality.’”(12) Adams wrote of his excitement about his print of El Capitan, Winter, Sunrise, which he made with Type 55 P/N film: “One look at the tonal quality of the print I achieved should convince the uninitiated of the truly superior quality of Polaroid film.”(13) Adams demonstrated technical points by making both creative and functional photographs, noting to Morse that “some of the recent pictures have been a very happy combination of feeling, purpose, and idea.”(14)

Yosemite/High Sierra: Tenuja Lake, test photograph by Ansel Adams, Type 55 P/N, 1967, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.52, f. 16.

Timber Cove, California, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1961, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, b. IX.42, f. 1.

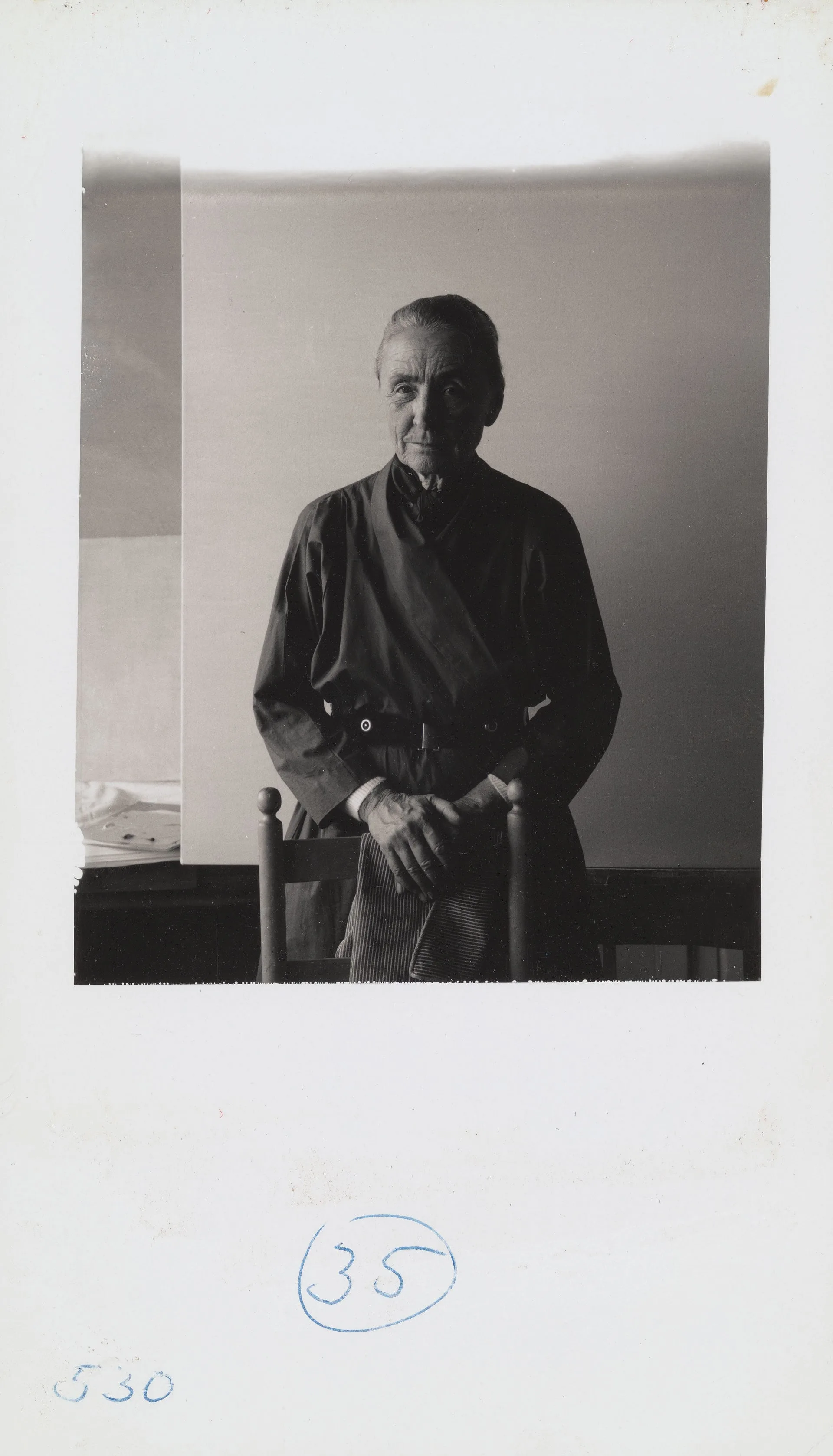

In Polaroid test photographs he took in California, the Southwest, and the Northeast, Adams focused on landscapes, architecture, still lifes, and portraits of his family and circle of artist friends. The photographer’s Polaroids began to appear in museum exhibitions and catalogues, and Adams actively encouraged other artists to work with the new medium, among them Imogen Cunningham, Walker Evans, Charles Sheeler, and Minor White.

In the spirit of Land’s vision of a fulfilling working life for those employed at Polaroid, Adams gave lectures and taught courses on the Polaroid process for company employees. He connected the rewards of personal creativity through photography with the satisfaction of being part of the process to create a photographic medium that would allow others to do the same. “A richer understanding of photography,” Adams wrote, “will result in the employee developing an awareness of the significance of his job as a participant in the photographic industry—in addition to offering him extended horizons of perception and expression."(15) As Vivian Walworth, who became senior manager of imaging materials research at Polaroid, remembered, “Both in the classroom and on our numerous field trips, [Adams] provided an exciting combination of teaching, encouragement, criticism, and above all, a sense of the joy of creating a photograph.”(16)

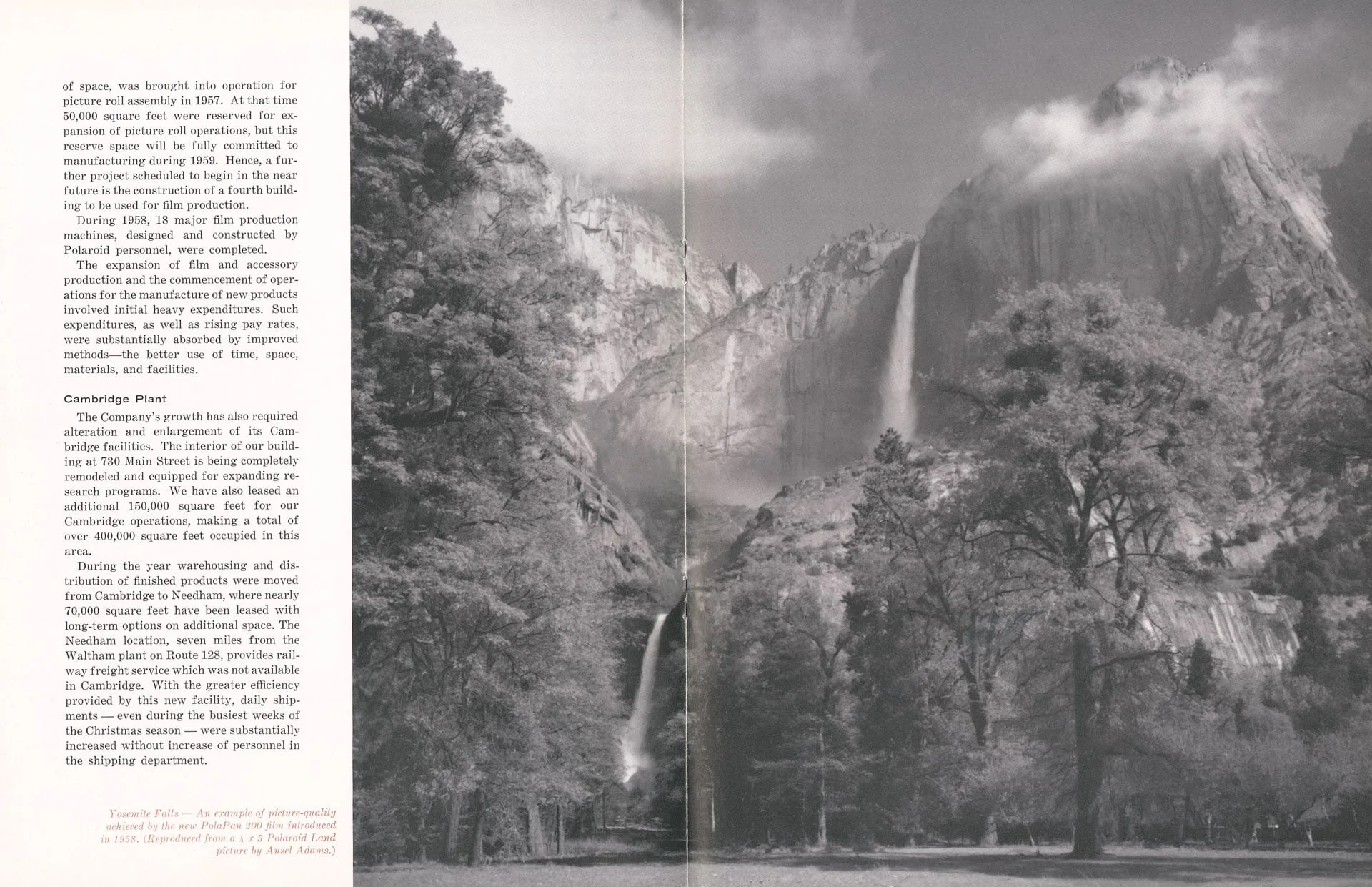

Morse championed Adams’s courses, which broadened conversations about instant photography in meaningful ways for Polaroid employees. Awareness of Adams’s Polaroid work also spread within the company through the publication of his images in Polaroid’s corporate reports. In 1960, Polaroid established a gallery for use as a classroom and an exhibition space to display Adams’s images and those of his students.(17)

Yosemite Falls, test photograph by Ansel Adams. Polaroid Corporation Annual Report, 1958. Polaroid Corporation Administrative Records, b. I.464, f. 22.

Adams shared his discoveries about instant photography to a broader public as well. Periodicals such as Aperture, U.S. Camera, and Modern Photography featured articles with Adams’s insights about the new medium from which both professional and amateur photographers could benefit.(18) In 1963, Adams wrote the Polaroid Land Photography Manual, which offered a comprehensive distillation of his many years working with Polaroid for those interested in the “creative-professional use” of the medium.(19) Adams was in demand for his workshops at Yosemite and around the country, where his use of Polaroid film and cameras introduced his students to the technology. Polaroid prints, developed instantaneously on site, also served as excellent teaching tools.

In the 1950s, company ads and feature articles in photography journals highlighted the rewards of the immediacy and ease of the process as well as the quality of the film.(20) The cover of a 1955 Modern Photography issue posed and answered the question: “Polaroid Cameras: Novelty or Marvel? Can Polaroid cameras take good pictures? Yes! Superb quality, fine detail, wide tonal range are found in the new film.”(21) Adams argued that photographic manufacturers “have a vast knowledge of advertising and sales, some of engineering, optics, physics, or chemistry, but none of aesthetics. Everything must relate to the marketplace . . . but Land believed that if the manufacturer includes objectives of highest quality in the social and aesthetic sense, all his products should benefit.”(22)

Paul Messier, founder and Pritzker Director of the Lens Media Lab at Yale’s Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, cites Morse’s work as “a great example of the need for the ‘translational’ role played by humanists working between the technical/scientific arm of an enterprise and the users, including artists like Adams. Recognizing the value of the ‘translational humanist’ at the table, in the increasingly corporate world of post-WWII America, took insight and a measure of courage from both Land and Morse.”(23)

In his years working with Morse and others at Polaroid, Adams learned the delicate balance of becoming “more resolute to the challenges of quality, yet more understanding of the realities of the marketplace.”(24) The dedication of Morse and Adams to the practical development and commercial viability of the medium coupled with their aspirations for its artistic potential reflected the manufacturing enterprise’s commitment to innovation and excellence.

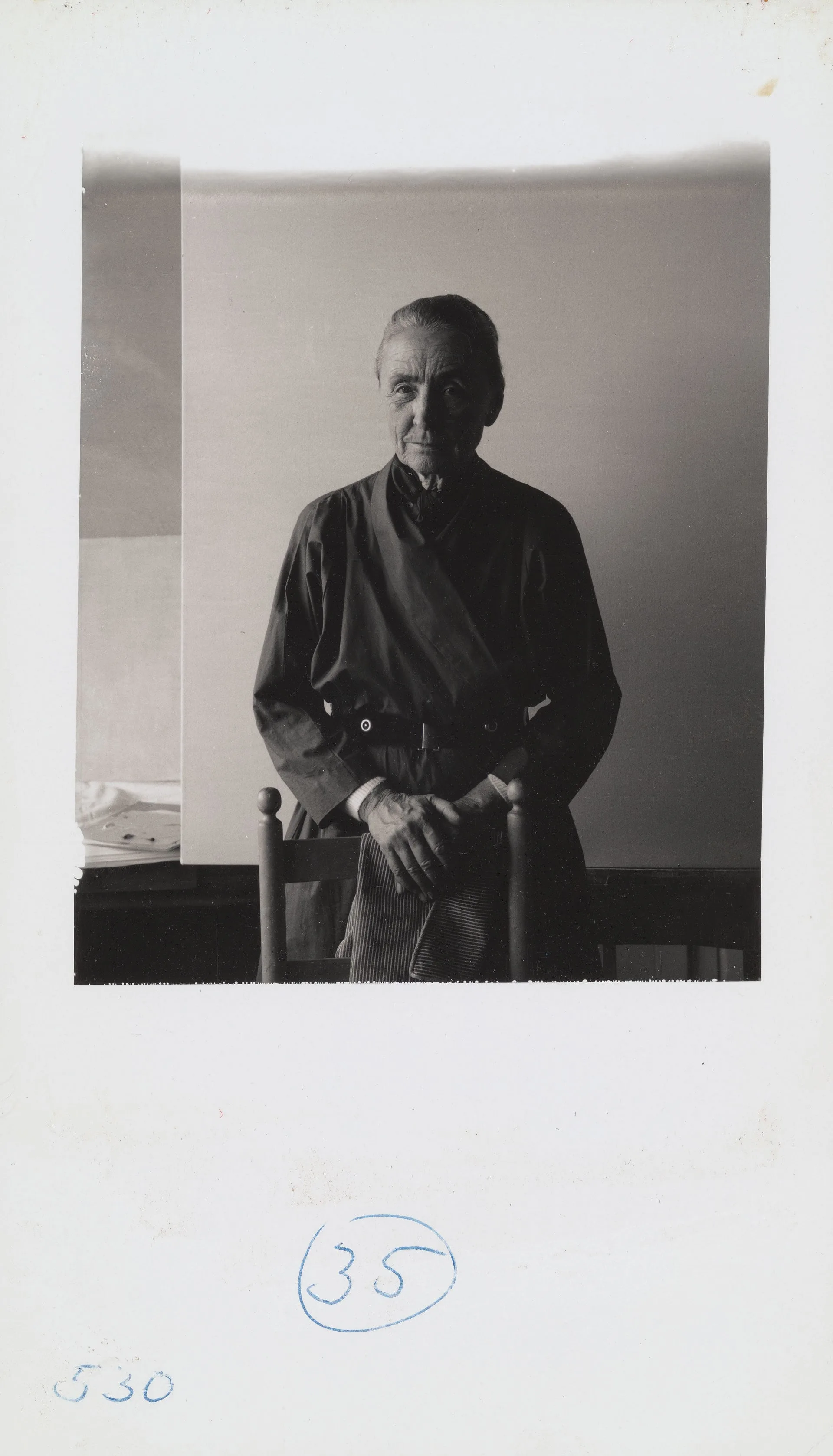

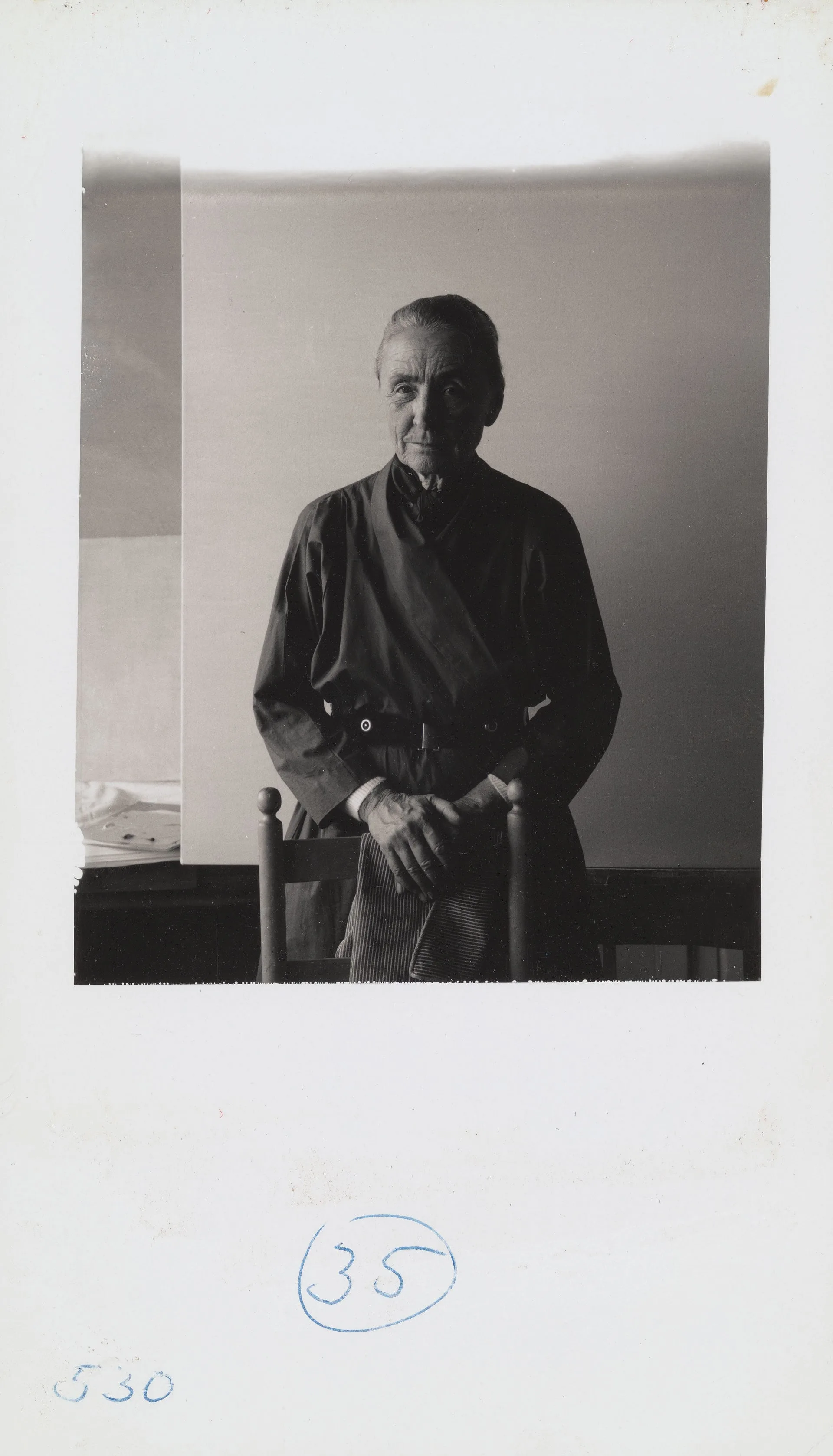

Georgia O’Keeffe, test photograph by Ansel Adams, November 18, 1956, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 35.

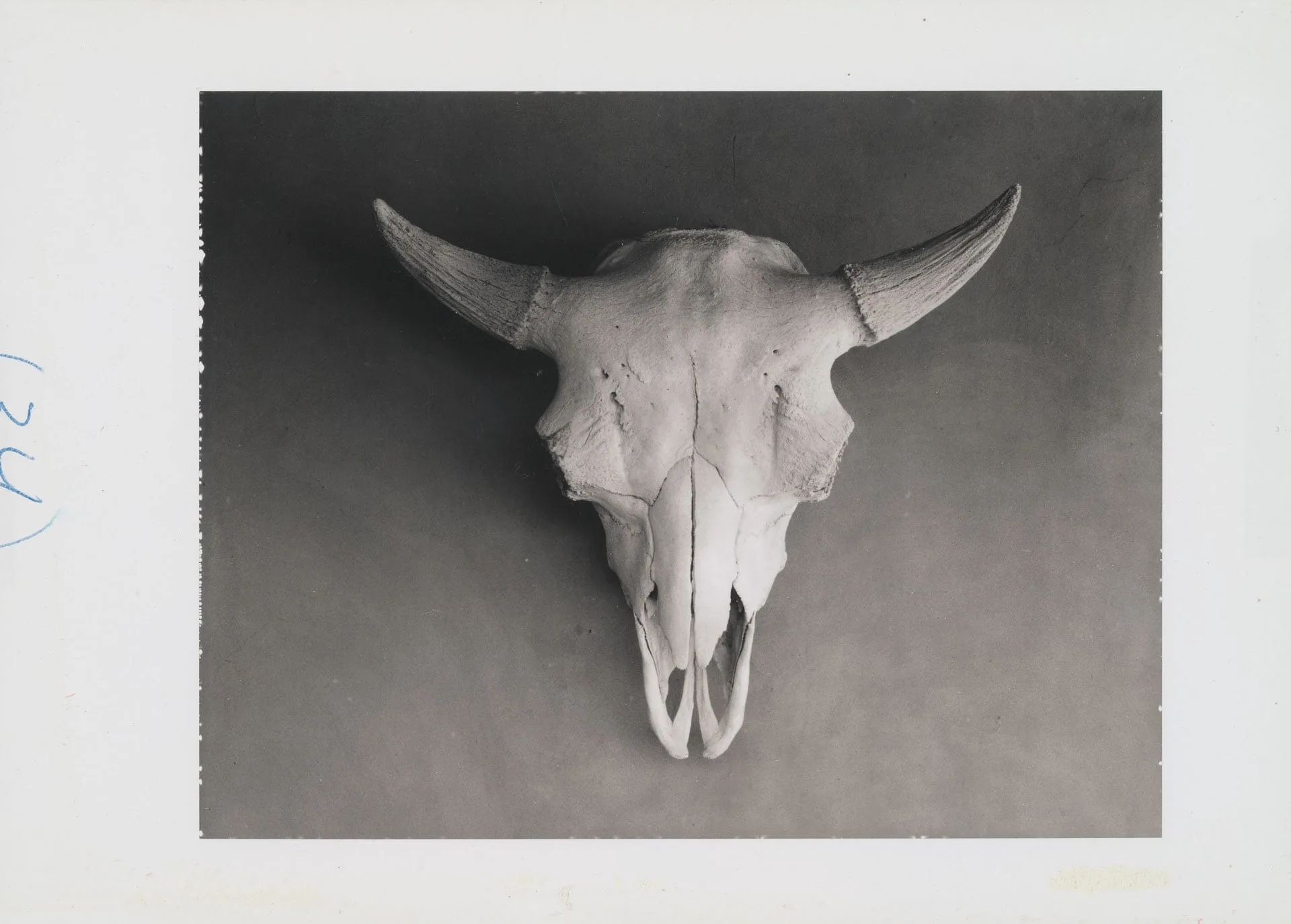

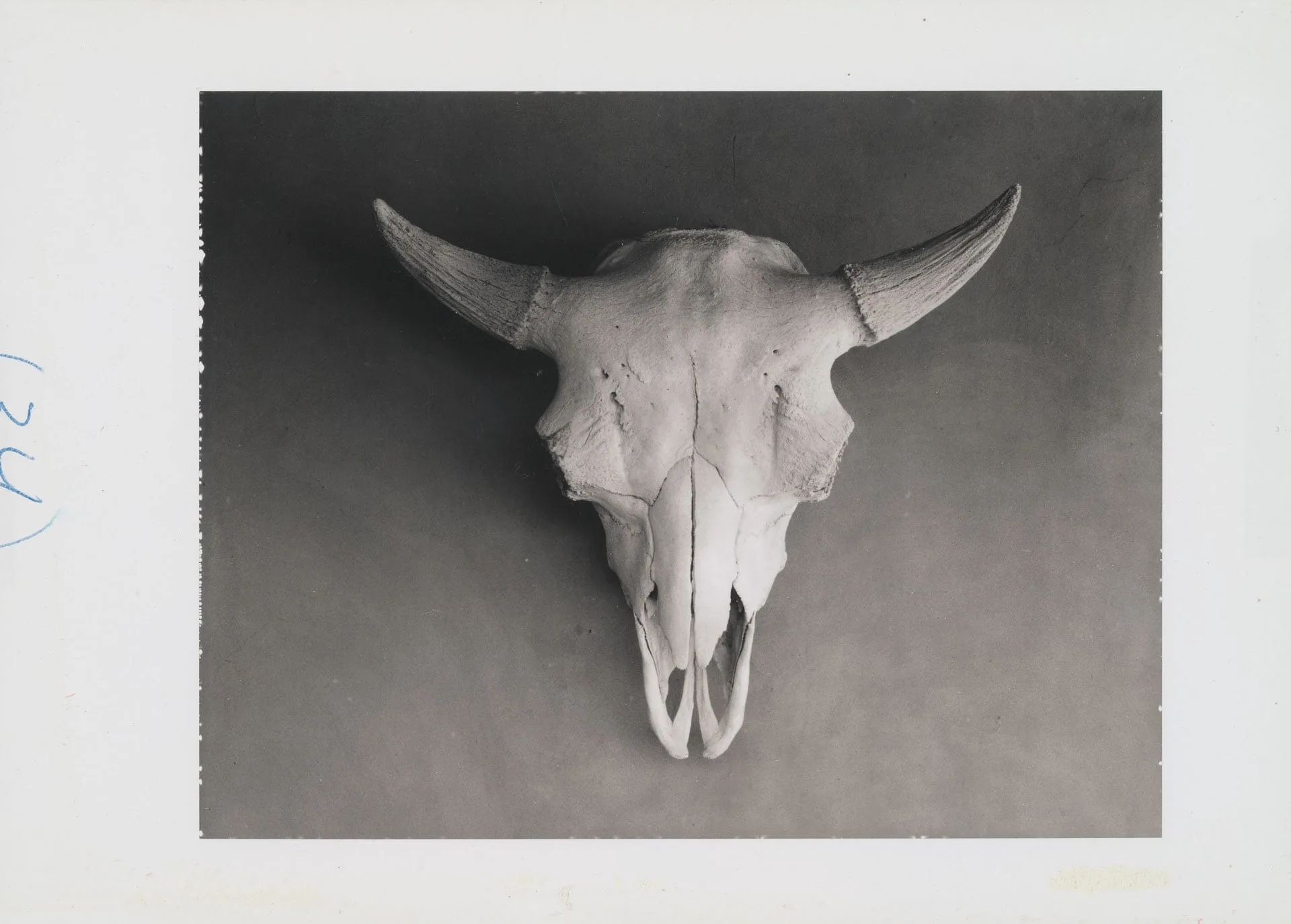

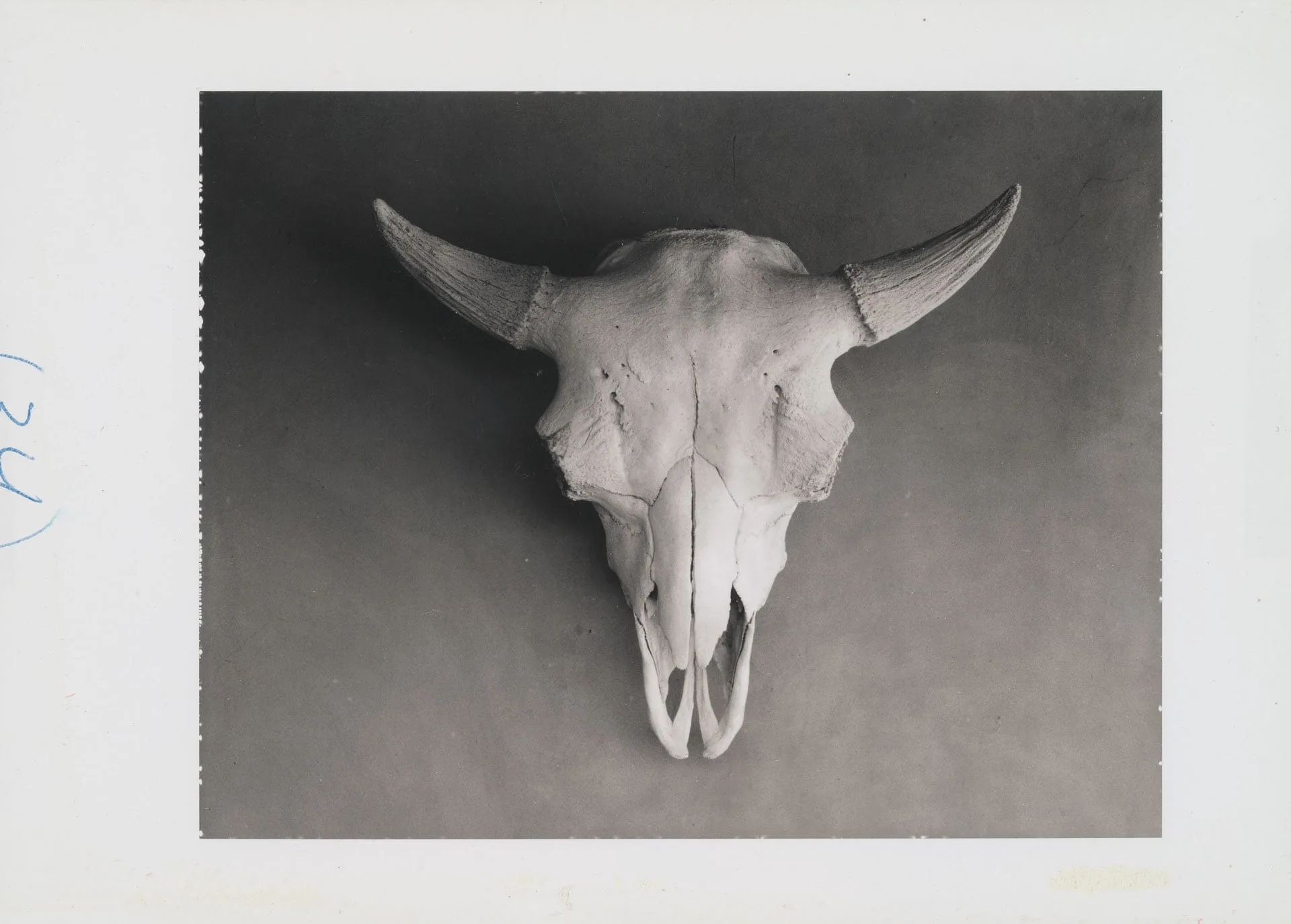

Skull on wall, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 36.

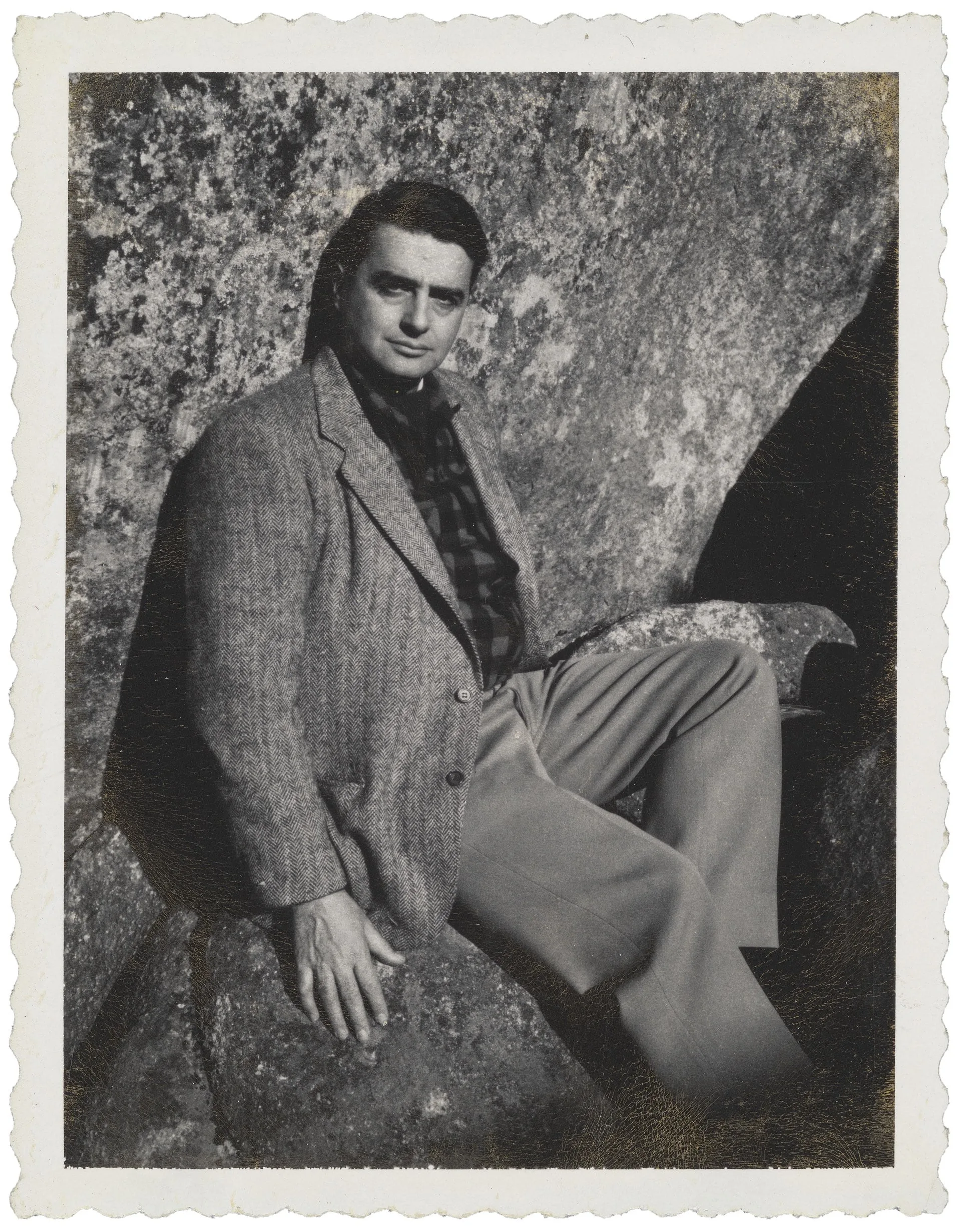

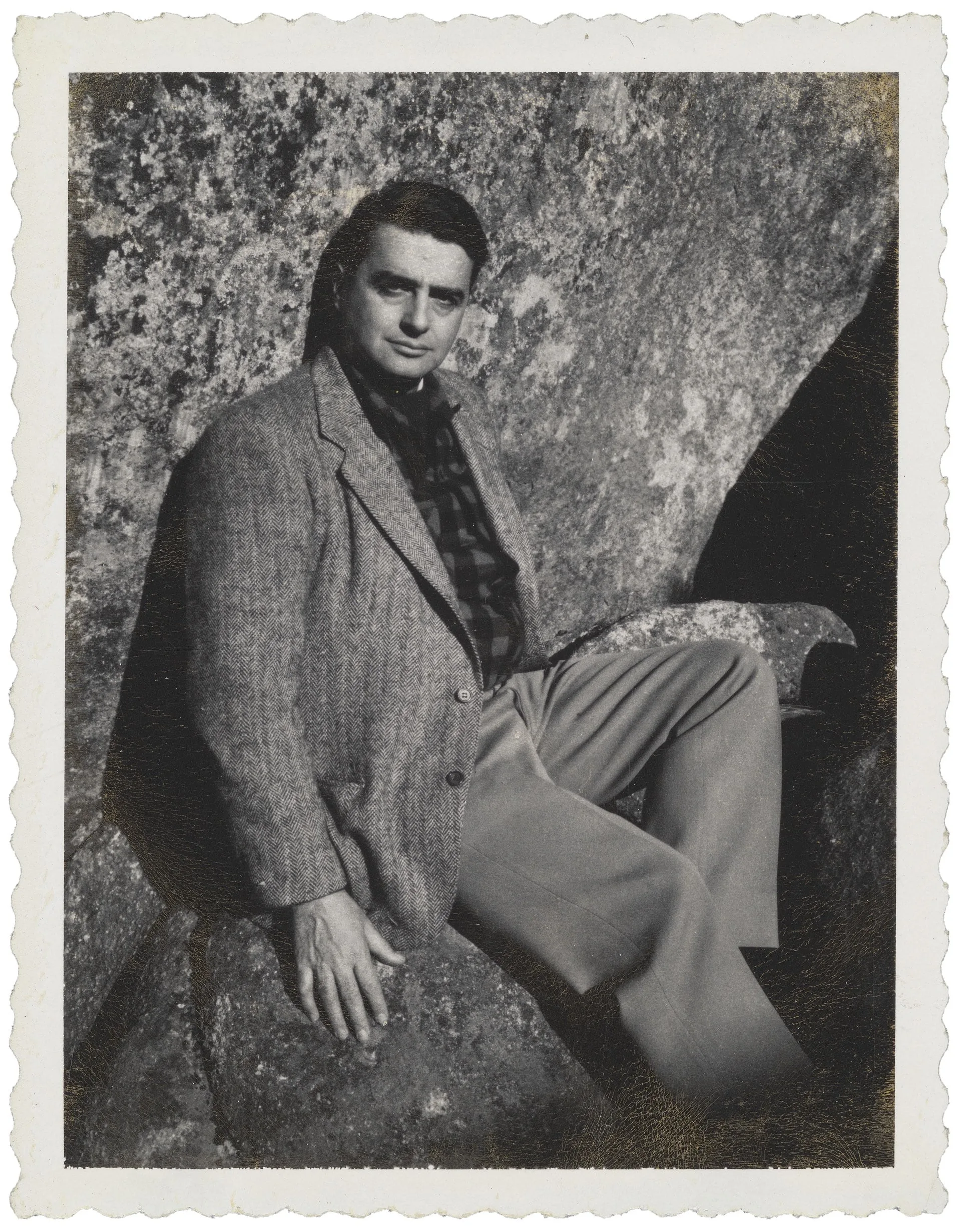

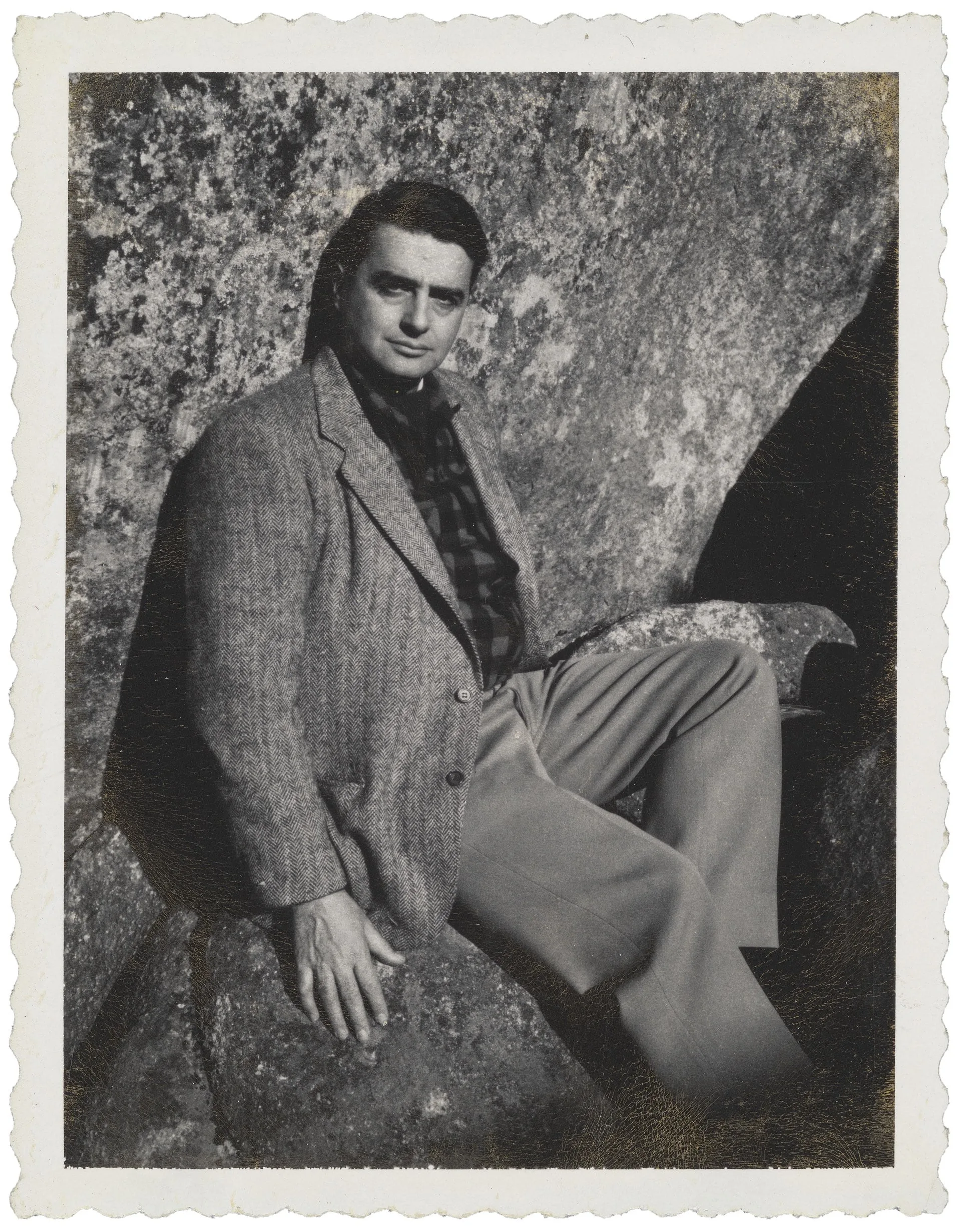

Edwin Land, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1953, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photograph & Visual Materials Collection, b. X.616, f. 4.

Skull on wall, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 36.

Edwin Land, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1953, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photograph & Visual Materials Collection, b. X.616, f. 4.

Georgia O’Keeffe, test photograph by Ansel Adams, November 18, 1956, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 35.

Edwin Land, test photograph by Ansel Adams, 1953, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photograph & Visual Materials Collection, b. X.616, f. 4.

Georgia O’Keeffe, test photograph by Ansel Adams, November 18, 1956, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 35.

Skull on wall, test photograph by Ansel Adams, ca. 1960, © The Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs & Correspondence of Ansel Adams, b. IV.13, f. 36.

Ansel Adams and Mary Street Alinder, Ansel Adams: An Autobiography (Boston: Little, Brown, 1985), 293.

Adams and Alinder, Ansel Adams, 295.

For discussion of Adams’s role as Polaroid consultant and in the design of Polaroid products see Jennifer Quick, “Designing Polaroid: Ansel Adams as Consultant.” American Art 35, no. 1 (2021), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1086/713575.

Ansel Adams, Examples: The Making of 40 Photographs (Boston: Little, Brown, 1983), 159.

Quick, “Designing Polaroid,” 31.

John McCann, personal communication with Melissa Banta, July 28, 2024.

Ansel Adams, “Playboy Interview: Ansel Adams,” Playboy (May 1983), 84. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.37, Folder 8.

Ansel Adams to Meroë Morse, February 13, 1954. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs and Correspondence of Polaroid Consultant Photographer Ansel Adams, Box IV.2, Folder 32. Adams also noted the film’s tendency to curl and streak (or what Adams called the “rubber cement” effect). See Quick, “Designing Polaroid,” 33–34.

Ansel Adams to Meroë Morse, December 26, 1962. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs and Correspondence of Polaroid Consultant Photographer Ansel Adams, Box IV.22, Folder 4.

Ibid.

Quick, “Designing Polaroid,” 32. https://doi.org/10.1086/713575.

Meroë Morse to Edwin H. Land, Thursday, August 10, 1950. Polaroid Corporation Records Related to Meroë Morse, Box VII.3, Folder 12.

Adams and Alinder, Ansel Adams, 302.

Ansel Adams to M. M. Morse, March 23, 24, 25, 1954. Polaroid Corporation Records, Photographs and Correspondence of Polaroid Consultant Photographer Ansel Adams, Box IV.2, Folder 9.

Polaroid Corporation News Letter, September 20, 1960. Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.38, Folder 4.

Vivian Walworth in “Ansel Adams 1902–1984 ‘—A Continuing Inspiration.’” Publication data unknown; copy in Polaroid Corporation Corporate Archives Records, Box IX.37, Folder 8.

The gallery was located in the company’s Kaplan building on Osborn and Albany Streets in Cambridge. The Polaroid Employees Photography Club also sponsored lectures, classes, and field trips.

On relationship between Aperture, Polaroid, and Adams, see Buse, The Camera Does the Rest, 177–189.

Ansel Adams, Polaroid Land Photography Manual: A Technical Handbook (New York: Morgan and Morgan, 1963), 5.

See Peter Buse, “Polaroid, Aperture and Ansel Adams: Rethinking the Industry-Aesthetics Divide,” History of Photography 33, no. 4 (2009), 354–369.

Modern Photography (May 1955), cover, 7.

Adams and Alinder, Ansel Adams, 297.

Paul Messier, personal communication with Melissa Banta, July 22, 2024.

Adams and Alinder, Ansel Adams, 297..