Investing in Emerging Industries

The third generation of Lehman Brothers partners included the sons of Sigmund M. Lehman: Allan S. Lehman who joined the firm in 1908 and Harold M. Lehman who joined in 1914. Robert Lehman, the son of Philip Lehman, took over leadership from his father in 1925. Robert’s uncle, Arthur Lehman served as a senior partner of Lehman Brothers until his death in 1936. In 1928, Lehman Brothers moved to One William Street, an eleven-story building, not far from their previous Wall Street location. The firm opened a branch office in Chicago in the 1930s and another in Los Angeles in the 1940s.

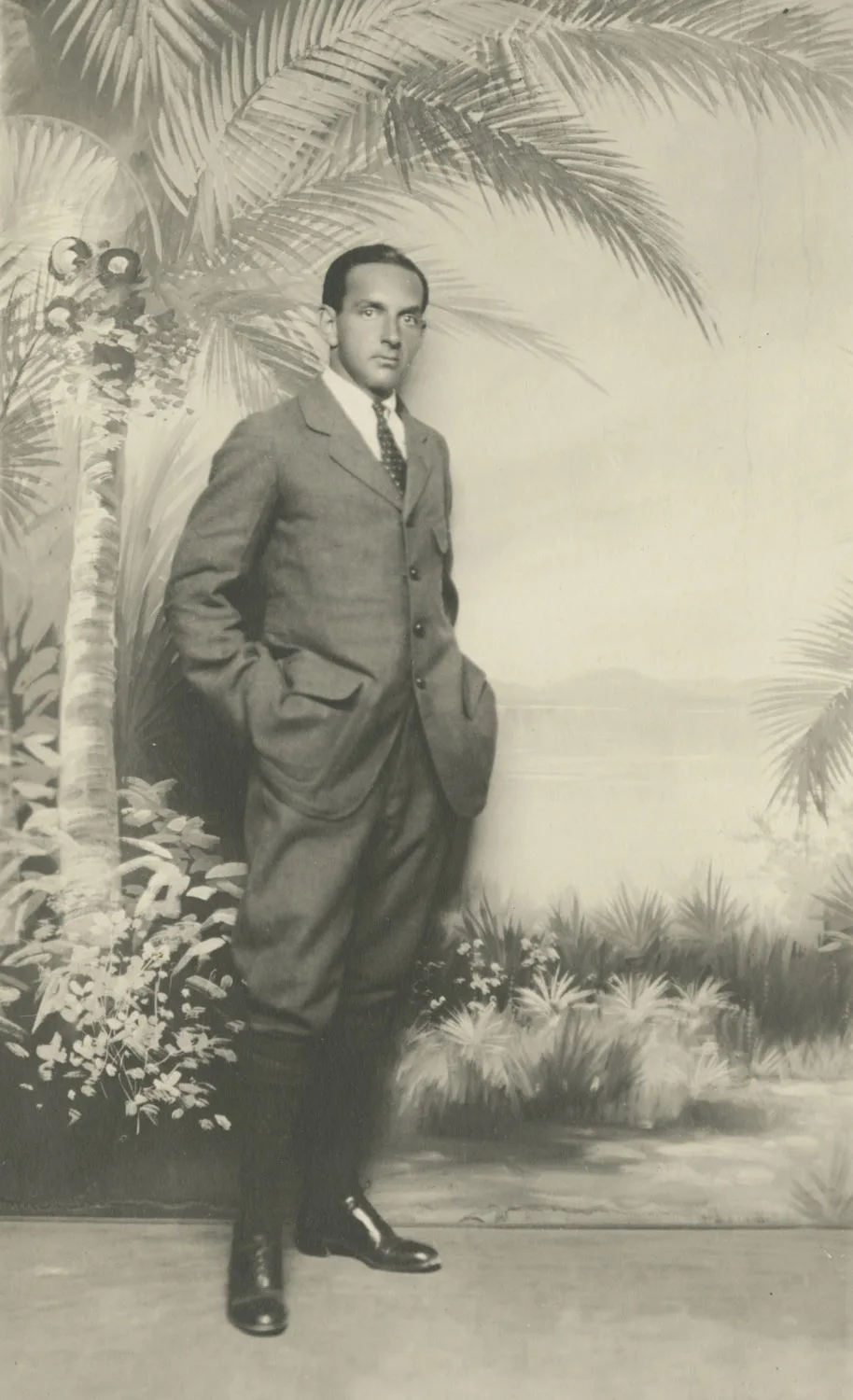

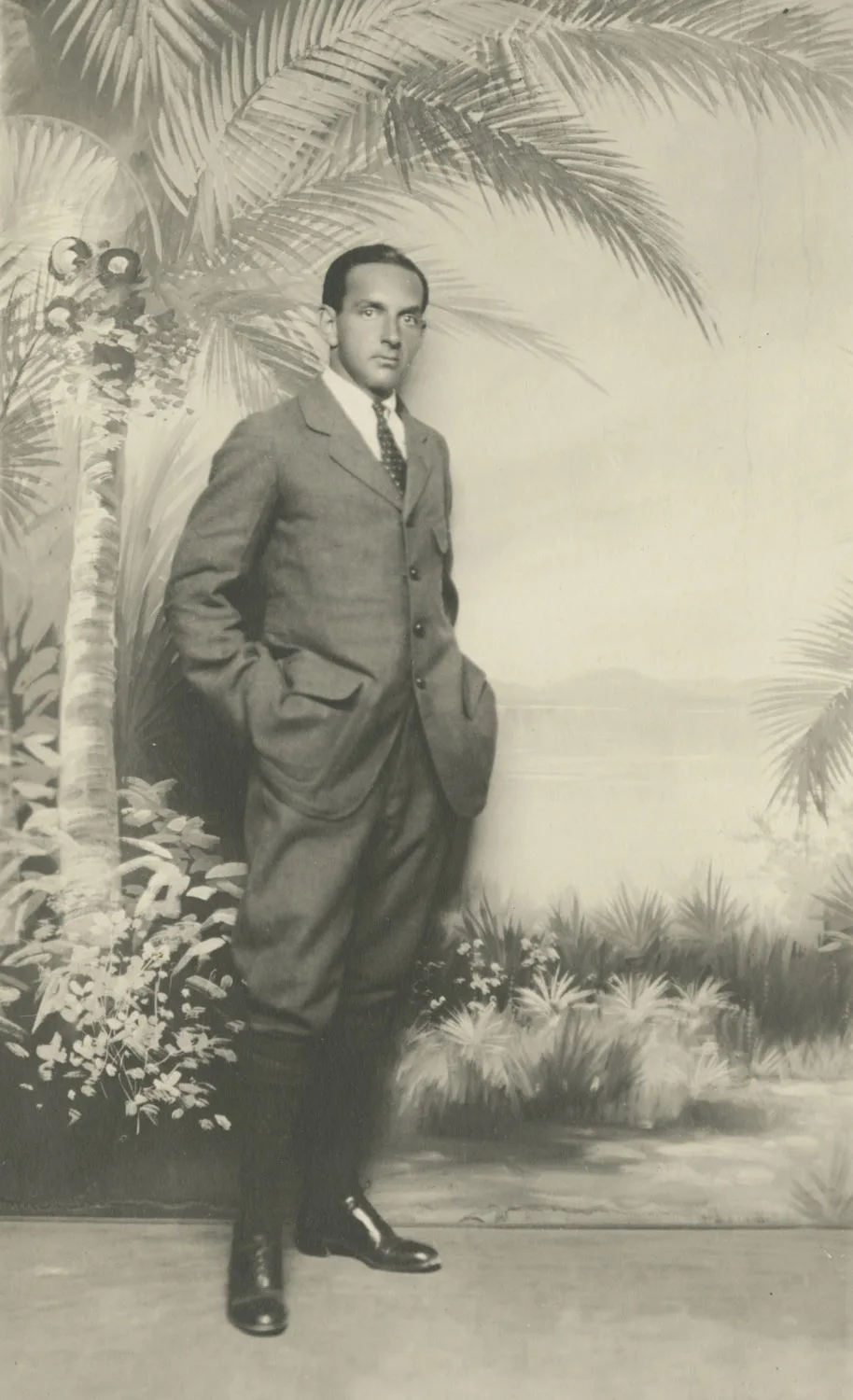

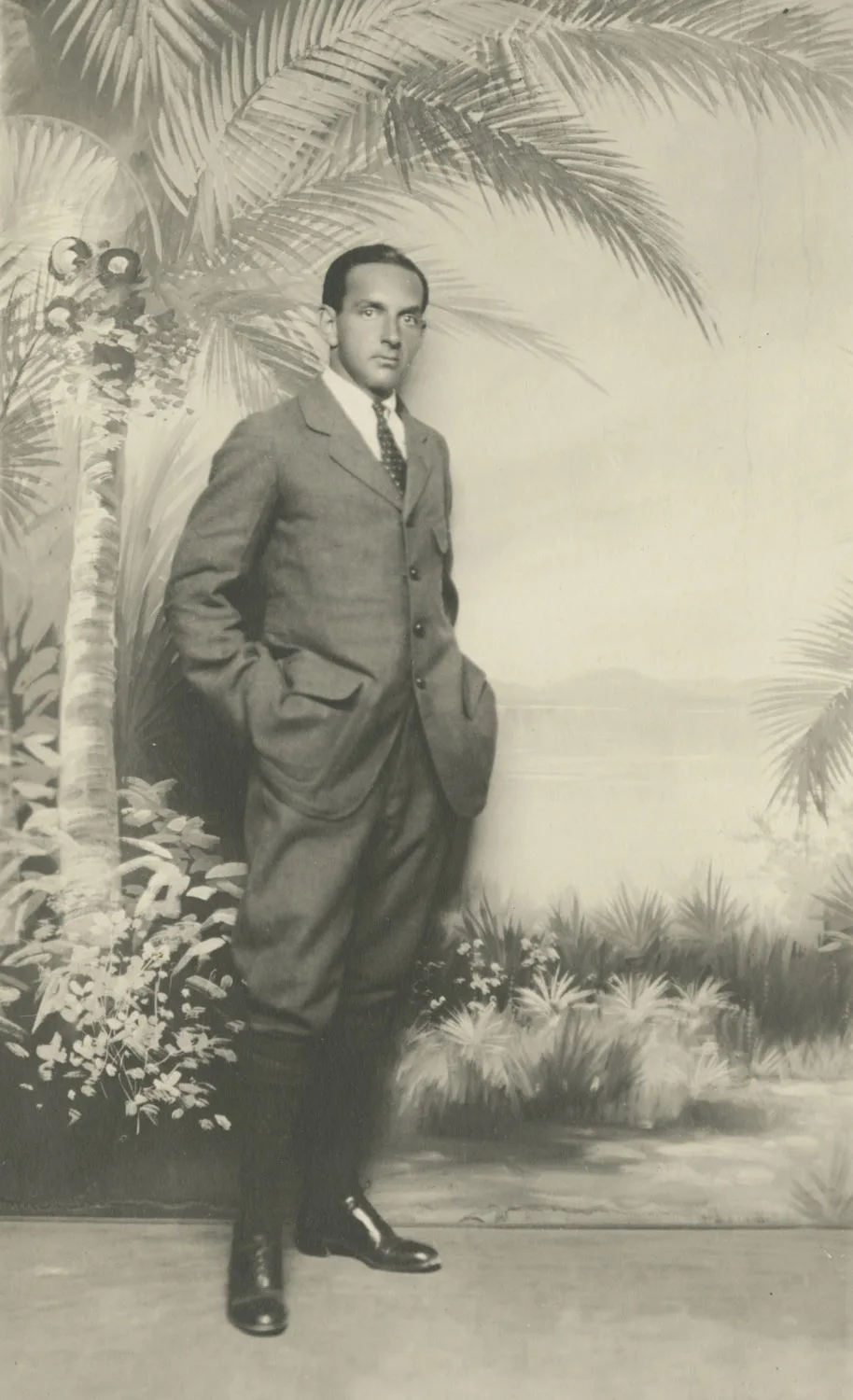

Robert Lehman, ca. 1915. Lehman Brothers Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Manhattan: William Street, 1923. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

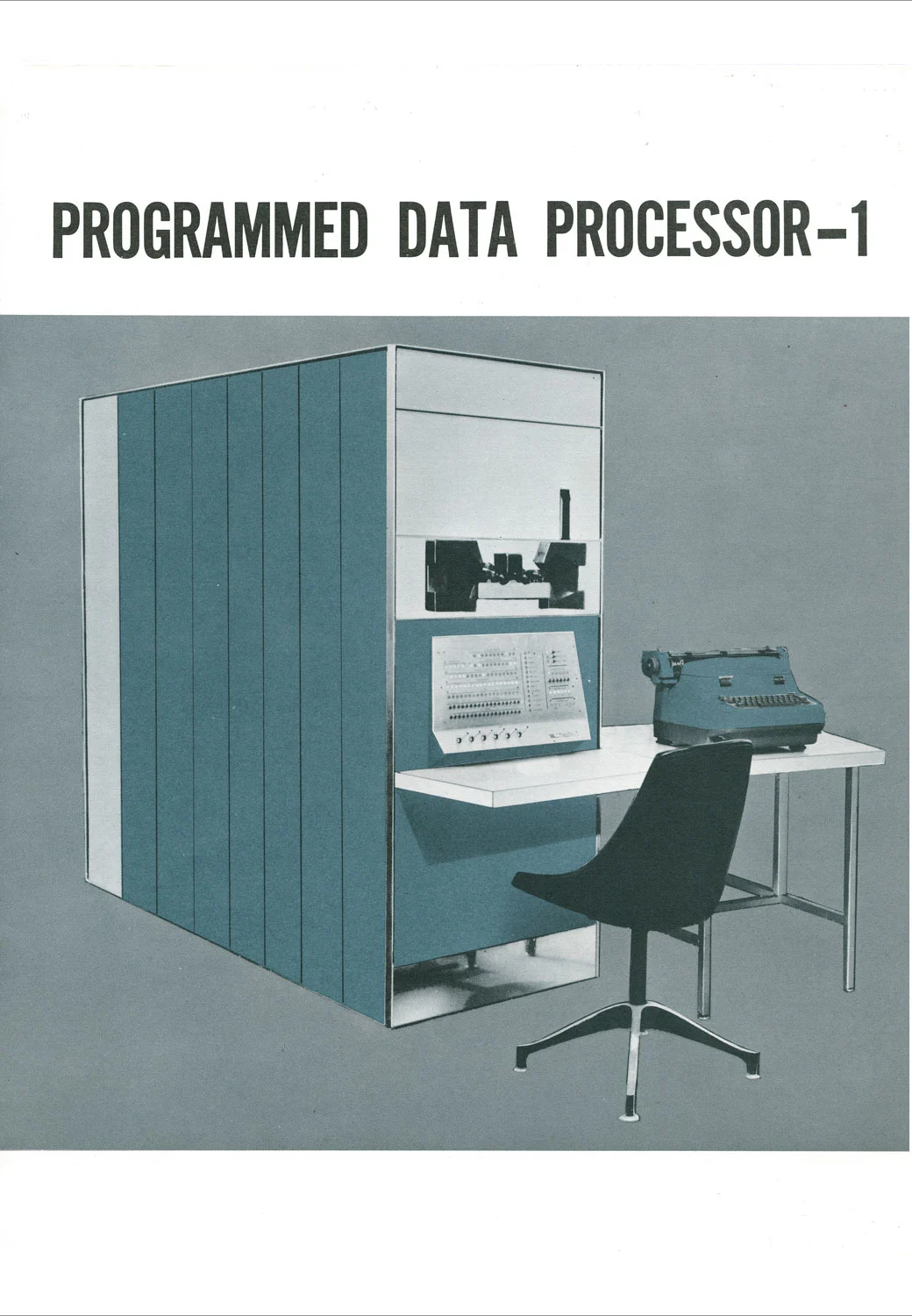

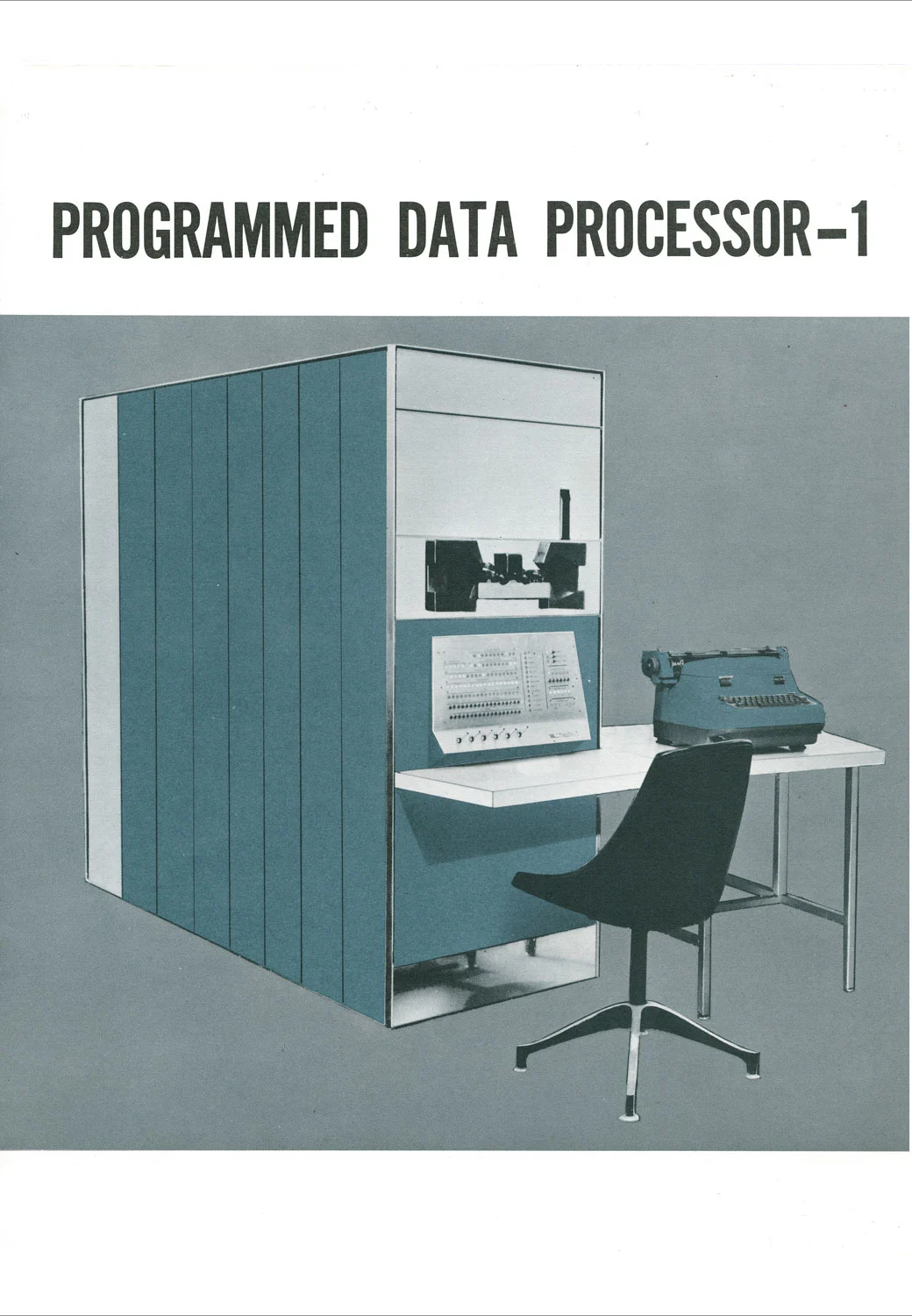

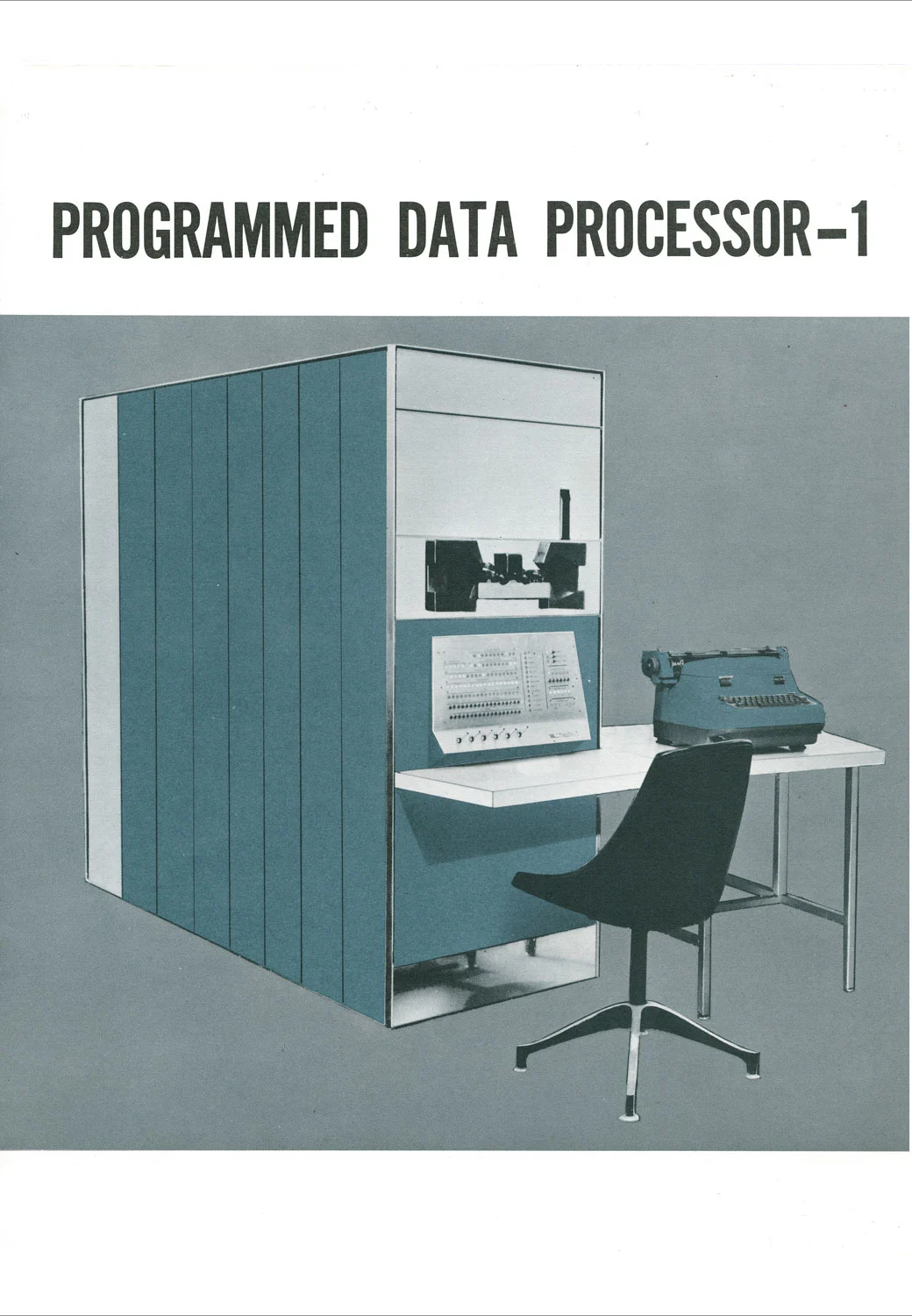

Digital Equipment Corporation. Programmed Data Processor-1 Brochure. Kenneth H. Olsen Collection, on permanent loan from Gordon College. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Manhattan: William Street, 1923. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Digital Equipment Corporation. Programmed Data Processor-1 Brochure. Kenneth H. Olsen Collection, on permanent loan from Gordon College. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Robert Lehman, ca. 1915. Lehman Brothers Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Digital Equipment Corporation. Programmed Data Processor-1 Brochure. Kenneth H. Olsen Collection, on permanent loan from Gordon College. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Robert Lehman, ca. 1915. Lehman Brothers Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Manhattan: William Street, 1923. The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Aerial view of Pan American Airways "China Clipper" over San Francisco, c. 1936. Prints & Photographs Division, Library of Congress, LC-USZ62-111417.

Lehman Brothers "partners' room," 1957. Courtesy of the Center for Creative Photography, The University of Arizona. Photo by Dan Weiner; Copyright John Broderick.

Robert, or Bobbie as he was known, guided the investment house toward the emerging enterprises he believed represented the greatest areas of growth. An early supporter of the aviation industry, Robert served on the board and was a backer of Pan American Airways Corporation, which started with flights to Cuba and grew into the country’s preeminent international airline. In 1929, Lehman Brothers helped establish AVCO (Aviation Corporation, later American Airlines, Inc.), and in the 1930s, the firm supported Transcontinental & Western Air (later Trans World Airlines, Inc.).

The motion picture business was another industry in which Robert Lehman saw potential. He advised on the merger of Keith-Albee and Orpheum theaters in the 1920s, which became RKO (Radio-Keith-Orpheum Corporation), creating a circuit of more than 700 theaters. Lehman Brothers also supported Paramount Pictures, Inc. and Twentieth-Century Fox Film Corporation. While the more established investment banking houses considered film studios a risky venture, by the late 1920s, movie attendance had skyrocketed to the millions, transforming the motion picture business into a major industry.

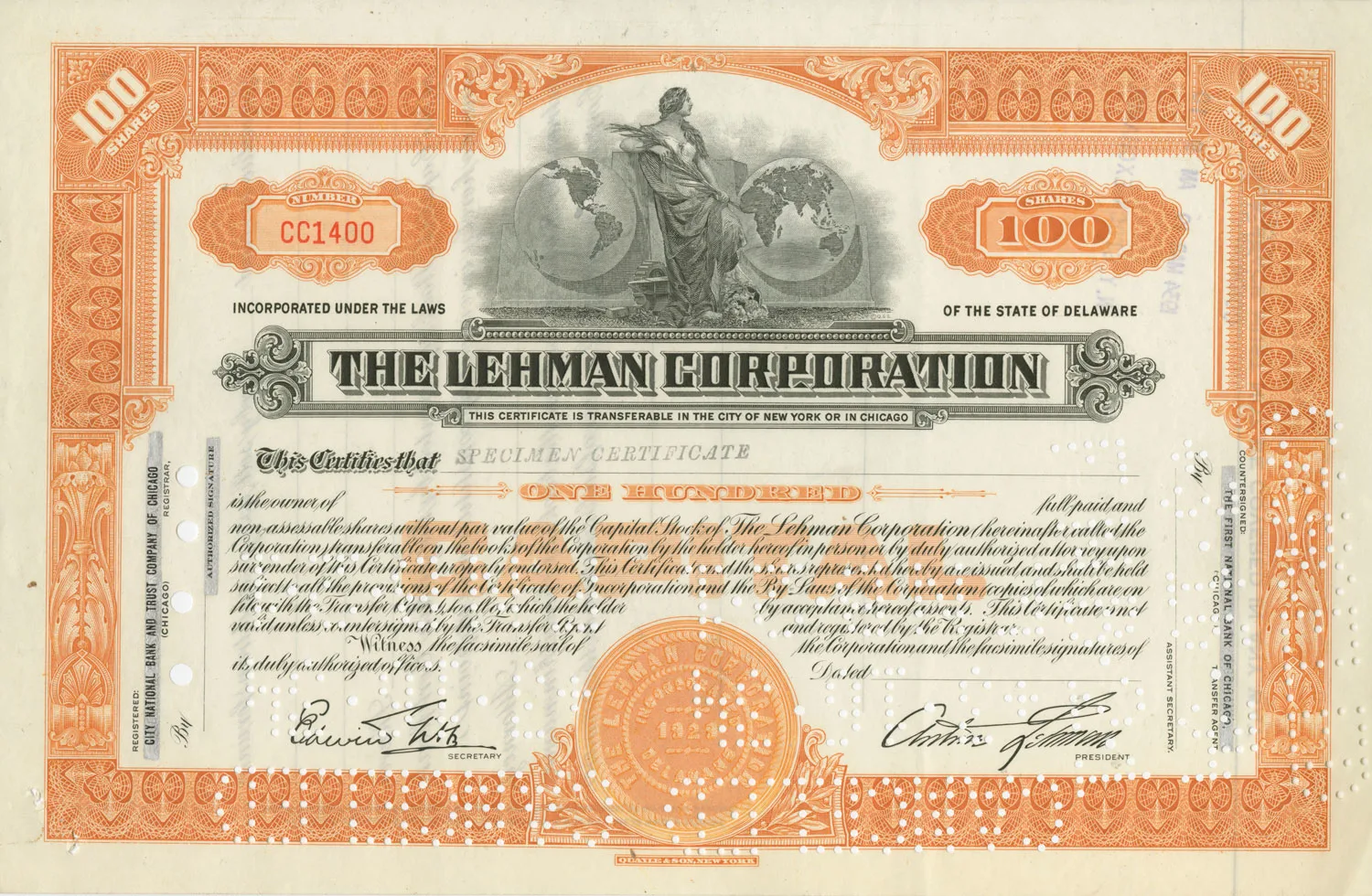

As the nation recovered from the Great Depression, Lehman Brothers continued to expand its underwriting activities. It issued the initial public offering of Allan B. DuMont Laboratories, a leading television equipment manufacturer of RCA (Radio Corporation of America). Other clients included Campbell Soup Company, B. F. Goodrich Company, and the Angelo-Chilean Nitrate Corporation. In 1929, the firm created its own closed-end investment company, the Lehman Corporation, which traded its own stocks and bonds on the New York Stock Exchange. “The management of someone elses [sic] money is a great responsibility under any conditions,” Robert Lehman wrote of the Corporation’s investment activities, “[requiring] the most exhaustive investigation, careful thought, and conservatively weighted appraisals.” (1) Lehman Brothers also created an investment advisory service for wealthy individuals and families. During the Great Depression when capital was difficult to raise, the firm instituted the “private placement” method that facilitated loans between blue-chip borrowers and private lenders with the assurance of lender safety and rate of return. This method of financing, a standard technique today, proved invaluable for companies trying to raise capital during this time.

Lehman Corporation Stock Certificate, 1929. New York Stock Exchange Archives.

In response to the Great Depression, the Glass-Steagall Act signed into law by President Roosevelt in 1933 called for the separation of commercial banks (that took standard deposits) from investment banks (that made investments with enterprises associated with higher risk). The following year, the government established the SEC (Securities Exchange Commission) to regulate the securities industry. Addressing the SEC in November 1936, Robert Lehman noted, any individual “will, through the very fact of control of a substantial amount of money, be in a position to obtain benefits improperly for himself, directly or indirectly . . . [which] can be controlled by appropriate legislation.” (2)

Lehman Brothers also focused on the oil industry, helping to finance TransCanada Pipelines Ltd., Penzoil Company, Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Company, and Kerr-McGee Oil Industries, Inc. Anticipating the future of the computer age after World War II, the firm supported established companies like IBM (International Business Machines) as well as emerging enterprises such as DEC (Digital Equipment Corporation), which produced a second generation of less expensive, compact computers for business as an alternative to mainframes. In the field of defense electronics, Lehman Brothers provided capital to Loral Electronics Corporation and supported entrepreneurs such as Charles “Tex” Thorton, who bought Litton Industries. In 1954, the firm issued securities for the Hertz Corporation, a pioneer in the car rental business that took off by the mid-1960s, and in 1956, along with a syndicate of other banks, Lehman Brothers made an initial public offering of the Ford Motor Company.

Lehman Brothers also entered the field of commercial paper, issuing short-term debt instruments (not required to be registered with the SEC) that came to serve as a major source of short-term financing. In 1958, the investment house launched the One William Street Fund, a mutual fund of diversified holdings funded by shareholders. Expanding their global reach in the 1960s, Lehman Brothers opened offices overseas, and the firm served in a financial advisory capacity in U.S. and foreign transactions. By 1966, Lehman Brothers, described by Time magazine as “a diversified department store of high finance,” ranked among the nation’s top investment banks in total dollar volume. (3)

Robert Lehman, “Investment Management and the Lehman Corporation,” undated, 3. Lehman Brothers Records, Baker Library, Harvard Business School, b. 674.

Robert Lehman quoted in “Banking House Advises SEC That Wider Curbs Are Desirable,” New York Times, November 11, 1936.

“Department Store of Investment,” Time, February 25, 1966.