Oral Histories

Transcripts

Betty J. Diener

(HRPBA 1963, MBA 1964, DBA 1974)

Interview by Livingston Grant, March 27, 2000. Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration Oral History Project, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

I always thought that the first year of the MBA when we were together in the Harvard Radcliffe Program gave us an opportunity to find a voice that we could articulate.

Betty Diener has balanced her career in academic administration with an ongoing exploration of environmentally sound business practices through her work in industry, marketing and new product development. She has taught at numerous institutions, including Case Western Reserve University, Old Dominion University, University of Massachusetts Boston, and Barry University Business School in Miami, Florida.

Learning about HRPBA

I had an opportunity to go to Wellesley College for my undergraduate degree and actually heard about the Harvard-Radcliffe Program there. The woman who headed up the alumnae office, excuse me, career services, whatever they called it at the time, had been a Harvard-Radcliffe Program graduate and made me aware of it and encouraged me to apply. I'd always had an interest in business and business management, but there just weren't that many places to go if that was your interest. Harvard wasn't accepting women directly. I had been accepted at University of Virginia, but really, you know, I was most interested in Harvard. So I applied to the Harvard-Radcliffe Program, and then at the end of that it was just about the time the Harvard-Radcliffe Program was ending.

And so we were told that Harvard Business School itself would be much more receptive to admitting women into their program, and I think we probably as a class had the largest number of Harvard-Radcliffe Program women accepted into the second year of the MBA. And so I went on to the second year of the MBA, not quite knowing what to do, and certainly the placement office didn't know what to do with us.

HRPBA & HBS Experience

Looking back on the Harvard-Radcliffe Program, which is such an anachronism now and we would all riot before we would do something like that, I guess, I just thought it was tremendously helpful. It was helpful in giving me the language of business so that I could talk effectively about it, and also some knowledge of numbers. I think that, in order for women to be credible in business or academia or government, you have to sound knowledgeable and confident, and that's the sort of thing that that program gave us.

Career

At that point in time they [Young & Rubicam] had never had a woman in their executive training program. They'd had women in research and women in media buying, but none in the account training area. So I went with them, and was the first woman to be in that training program, and stayed with them a number of years. I was an account executive on Eastern Airlines back when Eastern Airlines was still flying. And I worked also for American Cyanamid which at the time was Old Spice products and Formica products, worked in their consumer products division developing new products and had an opportunity to go back to Harvard.

But what Harvard did then was ask me, because we had such fun teaching the case, had I ever thought of getting a doctorate. Not only did they not have any cases about women, but they'd had fewer women that had gone through the doctorate. One that had was Margaret Hennig, who was also in our group. So I allowed as how that would be interesting. I don't think I'd ever thought of teaching as a career, but if you have a chance to go back to Harvard Business School for a doctorate, you sort of think that's pretty neat. So I went back. Because I'd worked for so many years, I think you get much more focused then you do when you're going through as an undergrad or as an MBA student. And so I was able to get through in about two years, and then started on a career that's been pretty interesting because it's combined academia, business at various times, and government.

In fact, when I went out to Case Western Reserve in Cleveland, I started a women's program in management out there because we were still in a time back in, let's see, back in the early seventies, this would have been like in 1975, there was still a time when women were reluctant to go into MBA programs. They didn't have the confidence even to apply for them. So we started a women's program in management that gave them the first two courses of the MBA in their own section, and then they went on and did a regular MBA program. And they really did gain a lot of confidence. They would go on to become the valedictorians of their MBA class, and the male faculty always were very surprised, like, "Gosh, how do they do it?" They have great natural ability. You just need to add the self-confidence to it.

Several years later suddenly had an opportunity to go back to Virginia, which was the state in which I'd been born and raised. I went back as dean of the business school at Old Dominion. Old Dominion's down in Norfolk, Virginia. When I was growing up in Virginia, it didn't even exist. It's one of these big emerging state universities that is growing by leaps and bounds and has 10,000 students and ten years before that hadn't even existed. And I was there for three years.

Then Chuck Robb was elected governor of Virginia and somebody put my name in the hat, and I interviewed with him and became his cabinet secretary for economic development and environmental protection, which normally isn't together in a cabinet position because there's a natural conflict between economic development and environmental protection.

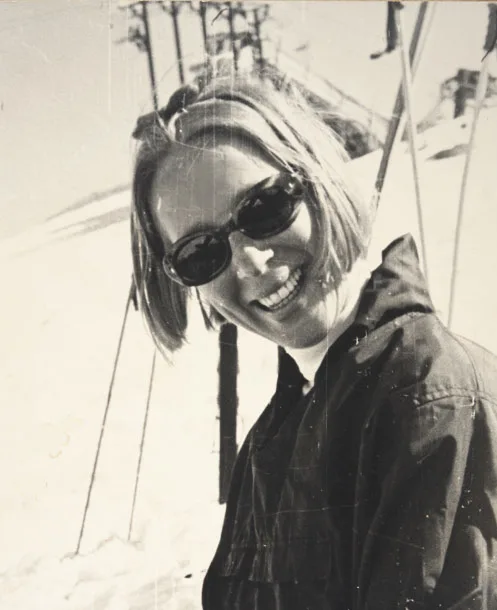

Elizabeth "Betsy" Latimer Jaffe

(HRPBA 1962)

Interview by Barbara Rimbach, March 27, 2000. Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration Oral History Project, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

I did have more confidence, and I did try other fields . . . . The discipline of the WAC program helped me with the doctoral program later . . . in writing my doctoral dissertation.

Betsy Jaffe is founder and president of Career Continuum, a New York career consulting firm, and author of “Altered Ambitions: What's Next in Your Life” (published, 1991). After HBPBA she went on to get her Ed.D at Columbia University. She started her career in retail as a department store buyer, and has used her experiences to consult, teach, and write on career management issues. Betsy Jaffe also worked for Catalyst, a nonprofit research and advisory organization that strives to build inclusive environments and expand opportunities for women and business.

It was 1961 when I went to A&S, and I saw that there was a young man there who had gotten an MBA at Wharton who made more money than I did, even though he had no experience. So that was kind of a trigger for me to say, “Hey, men are getting further than women and this isn't fair.” And he was making, I don't know, I think I made $95 a week and he made $125 or something. And so I knew of somebody who had been through the Harvard-Radcliffe program, and I talked to her about it, and she raved about.

And one of the women from the program came to New York to interview me. So she kind of knew what she was getting. I guess I was a little bit older than some of the people, but there were a few that were even older than I there in that year. That was 1961-62.

HRPBA & HBS Experience

At Harvard, I was impressed with the fact that we had the same professors that the men had. It didn't even occur to me at the time that they had this separate program for women and that wasn't there, but I wasn't thinking that way. I was just happy to be there and to be studying business topics because I'd been an art major in college. So I'd gone into business without any real training except some job experience. So the courses were challenging, and I met a lot of wonderful women there, and the WAC [Written Analysis of Cases] in particular was a challenge.

And of course I met my future husband there at a David Ogilvy speech at the cocktail party afterwards. He said he saw me across a crowded room and came over and invited me to a party. So that's how we met. And he had dated a lot of program girls.

We decided--he was in the midst of his doctorate, and he had four different supervisors over the years. It took him twelve years to get it. So during that time, we figured we'd have a better chance of him finishing it if we went to a quiet place like Storrs, Connecticut. So he became a professor there and I completed my MBA. I was the first woman and the only woman in their MBA program, which was attended mostly by Air Force officers who were older, but it was fine. I was pleased and proud of that, and then I went to work.

They accepted my credits from the HRPBA program and I started studying in I think September. I didn't have to go for the summer part, and it took me around nine months to finish. I was a marketing major there, and I did some independent study, research of a new big store that had moved in and changed the community, the impact on the community of that store so I was using some of the things I'd learned at the program as well as stretching further. And I still had an interest in retailing. I did, when I finished the MBA, interview in insurance companies and other kinds of companies that were in the Hartford area.

Career

I loved mentoring people, training people. I set up little programs for individual assistant buyers and I would say, "Well, this one needs a fashion sense, so we'll do some things to help her with that. This one needs math help. And you know. So I enjoy developing people. So I went and took a, I guess a certificate program at NYU in training and development, and left Gimbels, and wanted to switch into that field. I talked to Bloomingdales and they said, “Well, you're five years ahead of us. We're not into management development yet.” And I read this ad for Catalyst which sounded, you know, like a women/work combination. I took less money to go there, but it was very exciting, very stimulating. It was the beginning of the women's movement, they'd had these marches in New York, and I was new to that. I'd had my head into work and so wasn't too much aware of the women's movement going on, but once I got there I mean I was set on fire, and I persuaded Catalyst to go to the Women's Year in Houston where they had Betty Friedan, Gloria Steinem…thousands of women.

I started at Catalyst in 1977. So the women that were hired there at the same time I was became my best friends. I'm still friends with them. She hired wonderful people, but there was a lot of turnover. I stayed there five years. I was part of the Women Directors Roundtable, helped facilitate that. We pulled women directors from all the corporations together for a topic, and they met each other and networked. And I did a lot on starting corporate networks inside corporations. I would bring groups of women together and teach them what was going on with the most progressive companies, and bring those women as speakers, and not really the direction Catalyst wanted to go. It was a little, like, radical. But it caught on.

My book is called “Altered Ambitions: What's Next in Your Life?” It was primarily for women, even though it's very helpful to men too, the ideas, but it was, you know, you come to a point in your life where things must change. Things can't go on as they are, and here are some processes that might be helpful for you. We had five model women of different types in it, and their problems and progress through each chapter. So each woman was a composite of many of the women that I've met over the years.

Judith Prior Lawrie

(HBRPA 1958)

Interview by Barbara Rimbach, March 27, 2000. Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration Oral History Project, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

I've always said, having gone to the Business School, I knew the jargon. I mean literally I spoke the same language from day one. And so I tended to be accepted intellectually by young businessmen.

After graduating from HRPBA in 1958, Judith Lawrie worked for consulting firms that specialized in transportation issues and the emerging field of software development. Concentrating her strengths and areas of interest, she later worked as an analyst and portfolio manager for mutual funds specializing in technology. In 1983 she was the founding partner of HLM Management Co.

Learning about HRPBA

In 1953, I was not married or seriously engaged. I knew I didn't want to be a secretary, and I knew I didn't want to go to graduate school in English because it would mean merely putting off the moment of teaching, because inevitably it would lead to teaching. So a friend of mine from high school was at Cornell, and through a friend of hers had heard of the Radcliffe Program. And so I probably heard about it that winter or spring of my senior year.

So I applied to the HRPBA program. Rosemary Bachman came through Ann Arbor and interviewed me. I don't know why I remember that, but I do. And fortunately I was accepted and given, as I recall, a scholarship and a loan to make it possible. So for the age of twenty-one, I went east of Detroit for the first time in my life. I had never been to the East Coast, which I thought was very exciting. I enrolled in the program and lived at fifty Concord Avenue, which I don't think the College still owns.

HRPBA & HBS Experience

I did my fieldwork at Gilchrist's in the fall, and worked in the children's department of Gilchrist's basement, selling snowsuits. That was an eye-opener. I had never done anything like that, of course. Then in the spring I was at a new little company in Cambridge called Tech Built, which had created a design for a partially fabricated house. And there was two-hour special about them; Ford Motor used to sponsor Sunday afternoon television program, and I don't remember what they called it, but that was in the days when you did two-hour specials on nothing because there was no content to put on TV. And this little company had been swamped with orders. Really swamped. Thousands of inquiries from all over the country from builders, people who wanted to build a house, because it was modern.

It was a company with probably twelve employees at that point. So working there involved anything from running up to the company that made blueprints up on Church Street for extra blueprints, to going in on Saturday and opening the mail to see if there were any checks so we could meet the payroll. So I worked. I was essentially the only quasi-clerical office administrative person. And free. Of course they appreciated it being free.

They weren't able to pull it out, as it happened and finally they eventually did go bankrupt. But it was a very interesting experience, of course. Because they were inventing the company as they went along.

I've always said, having gone to the Business School, I knew the jargon. I mean literally I spoke the same language from day one. And so I tended to be accepted intellectually by young businessmen. And had I gone into those things with just a liberal arts degree, I'm not sure it would have been the same outcome.

My other favorite observation on the School which everybody's heard a hundred times is that the B School, I think, can make a good man better, but it can't make a bad man good. I think in my case it gave me the jargon and the confidence and some understanding of what the process was about. Certainly none of us knew that the first day we showed up. What's business? It was not in a young woman's vocabulary at the time.

Career

When I graduated from Harvard, I went to work for a company that had been created by Paul Cherington who was then the transportation professor at the School. And this was a consultancy that dealt primarily with transportation matters, but almost entirely with the airlines. And had a big specialty in developing the case work for what was then the Civil Aeronautics Board hearings. And we did such things as a market study for North American aviation on whether their new Sabreliner jet aircraft would have any takers. All kinds of things related to it. The company was run by Dee d'Arbeloff, who went on to run Millipore, whose brother is the founder of Teradyne. And it was a very interesting experience to work for Dee. He was barely older than I was, probably twenty-eight or twenty-nine. And there again, it was a company with probably twenty employees on Mt. Auburn Street, right across the street from Tech Built. And in that case I was hired in as a research assistant, not a secretary. That was a giant breakthrough.

The money management business and the mutual fund business was very young at that point. What I came to realize after having been with Wellington for two to three years was that the nice thing about the money management business is it's a meritocracy. It is true that seniors can always claim credit for new ideas, but at some point it becomes obvious whether they have the talent for it or not.

That's what's kept me at it for thirty-three years now; it's a brand new world every day and I love it because I get up in the morning and I don't know what's happened overnight, but something has changed every morning, and away we go. And I remember the other thing about the early days, saying to somebody, "This has to be the best job in the world because I'm being paid to read."

Lloyd Adams Mitchell

(HRPBA 1957)

Interview by Barbara Rimbach, March 27, 2000. Harvard-Radcliffe Program in Business Administration Oral History Project, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University.

I really quite enjoyed (the classes), I especially liked the ones dealing with people: the personnel management, time-and-motion studies, the puzzles and games.

Lloyd Mitchell's first job after graduating from HRPBA in 1957 was in the sales department at Polaroid Corporation. Later she moved to a Director of Public Relations position with The Architects Collaborative in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She led public relations for architect John Carl Warnecke in Washington, D.C. and San Francisco and worked as a private consultant for numerous architectural firms before shifting gears and starting a successful vineyard and winery in Rhode Island with her husband.

Learning about HRPBA

I didn’t come out of Stanford with a real vision of where I was headed. I went to see the Dean of Women, and she suggested the Program. I will never forget her saying, “This is the beginning of the decision-making period for you - the chance to be in charge of your own life.”

There were five of us from my class at Stanford that came to the Program. Three of us shared a room, and the other two were in a different house.

HRPBA & HBS Experience

I guess we all remember the Jackson case. It was the first case they gave us. It was quite a change from what I was used to. Instead of opening a lot of books and going to lectures, you had these cases. I like puzzles and games, so I treated most cases as puzzles and games. I have never forgotten when the professor (I can’t recall his name) is going around the room asking all these charming, smart ladies, “What’s the nugget here? What is the real key to the case?” And they didn’t get it. When he got to me, I was almost embarrassed to speak, but I said, “It’s the waste. It’s the salvage”. He said, “Yes!” It just set me up for the whole year.

That did it for me. I really quite enjoyed all the cases. I really liked very much the ones dealing with people: the personnel management and the time-and-motion studies I didn’t love writing the WAC’s, but I didn’t mind it either.

Career

In the Fall of 1957 I went to work for Polaroid Corporation. I thought it was quite wonderful. I was hired to help pioneer the transparency film which meant I was in the Sales Department reporting to the Industrial Sales Manager who was a perfectly charming guy named Kemon P. Taschioglou! His boss was my great favorite" a man named Stan Calderwood. These were exciting times for Polaroid. It was definitely a growth industry.

Then one day I just walked into The Architects Collaborative on Brattle Street and left a letter with a resume and said I would be very interested in coming to work there. They called me up, and before you knew it, I was there. That was September, 1958.

From the get go I was in charge of Public Relations. In those years architects were not allowed to advertise so the only way they got work was keeping abreast of the potential projects in the area, getting the work they had finished published in the media – both local and national as well a professional, and developing brochure materials that were attractive and well defined. I did all that stuff, and I enjoyed it. The firm began to grow. When I joined them there were 28 people, mostly partners and associates, and when I left 18 years later, we were 350. It was big. As someone said, “It’s another growth industry”.

During this period I also had an offer I couldn’t turn down to work with an architect named John Carl Warnecke. By this time Gropius had died, and TAC was changing. Warnecke was the architect for the John F. Kennedy Grave in Arlington National Cemetery, and he needed help with the press. It was a terrific challenge. The firm also had offices in San Francisco and Honolulu so it was an chance to see the world. I worked with Warnecke for two and a half years before returning to TAC in 1967.

In 1973 I married James A. Mitchell, a senior International Consultant at Arthur D. Little. Since we had met and married later than most, we decided we wanted to work together on a project that would combine a land use and an art form in a small business. As a result we established Sakonnet Vineyards in Little Compton, Rhode Island which became the premier vineyard and winery in New England. We sold the property in 1987 and retired to Camden, Maine.