Bankruptcy

By 2008, Lehman Brothers was massively invested in mortgage-backed securities. Erin Callan Montella, appointed CFO in late 2007, says she quickly “came to understand how the mere existence of a concentrated portfolio of mortgage assets on our balance sheet was a big problem, regardless of any quality or hedging arguments that might be made.” (1)

Glen Le Lievre, "Too big to fail." The Wall Street Journal Cartoon Collection, Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Lehman Brothers sign taken into Auction House in London, September 24, 2010. Courtesy of AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth.

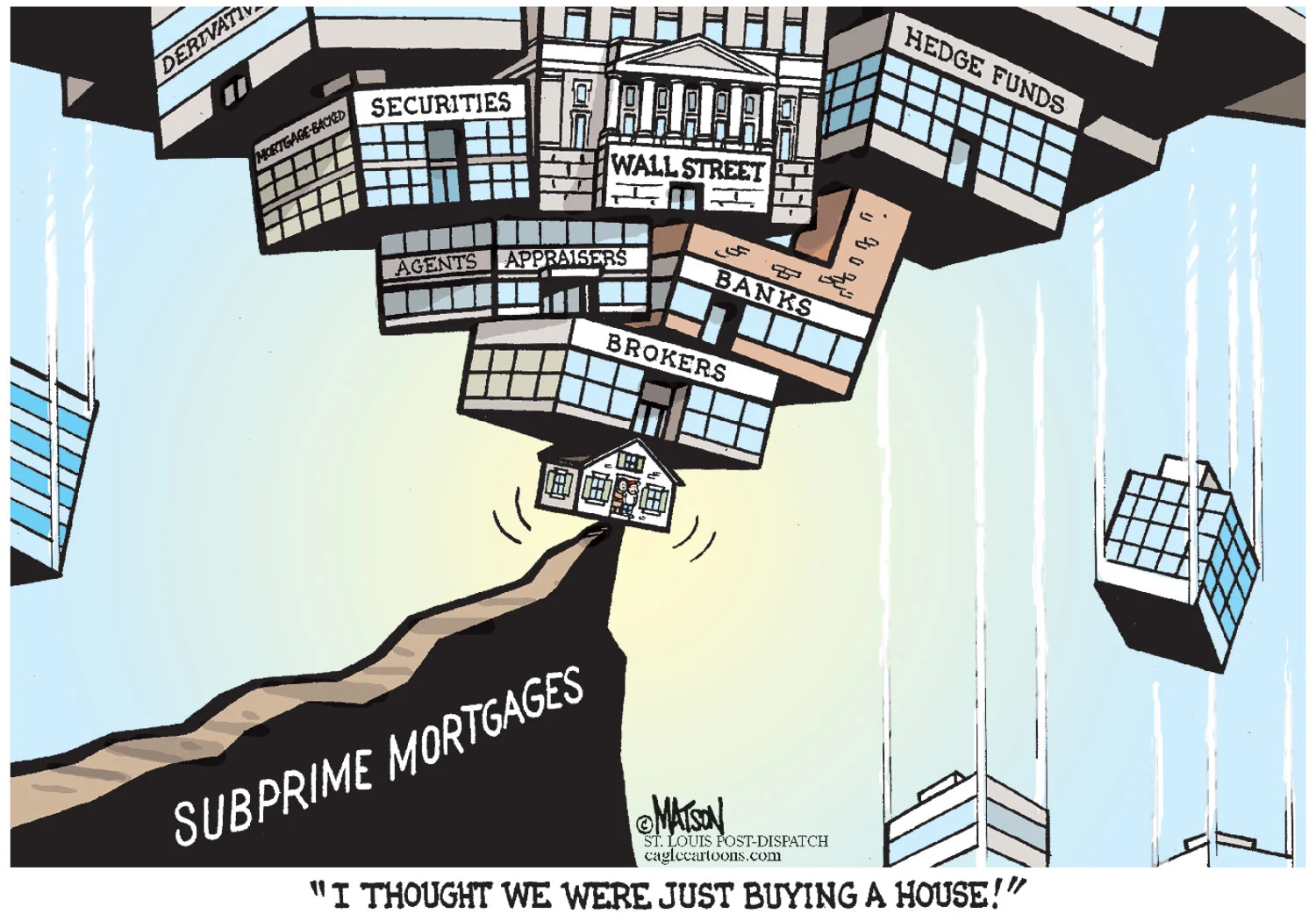

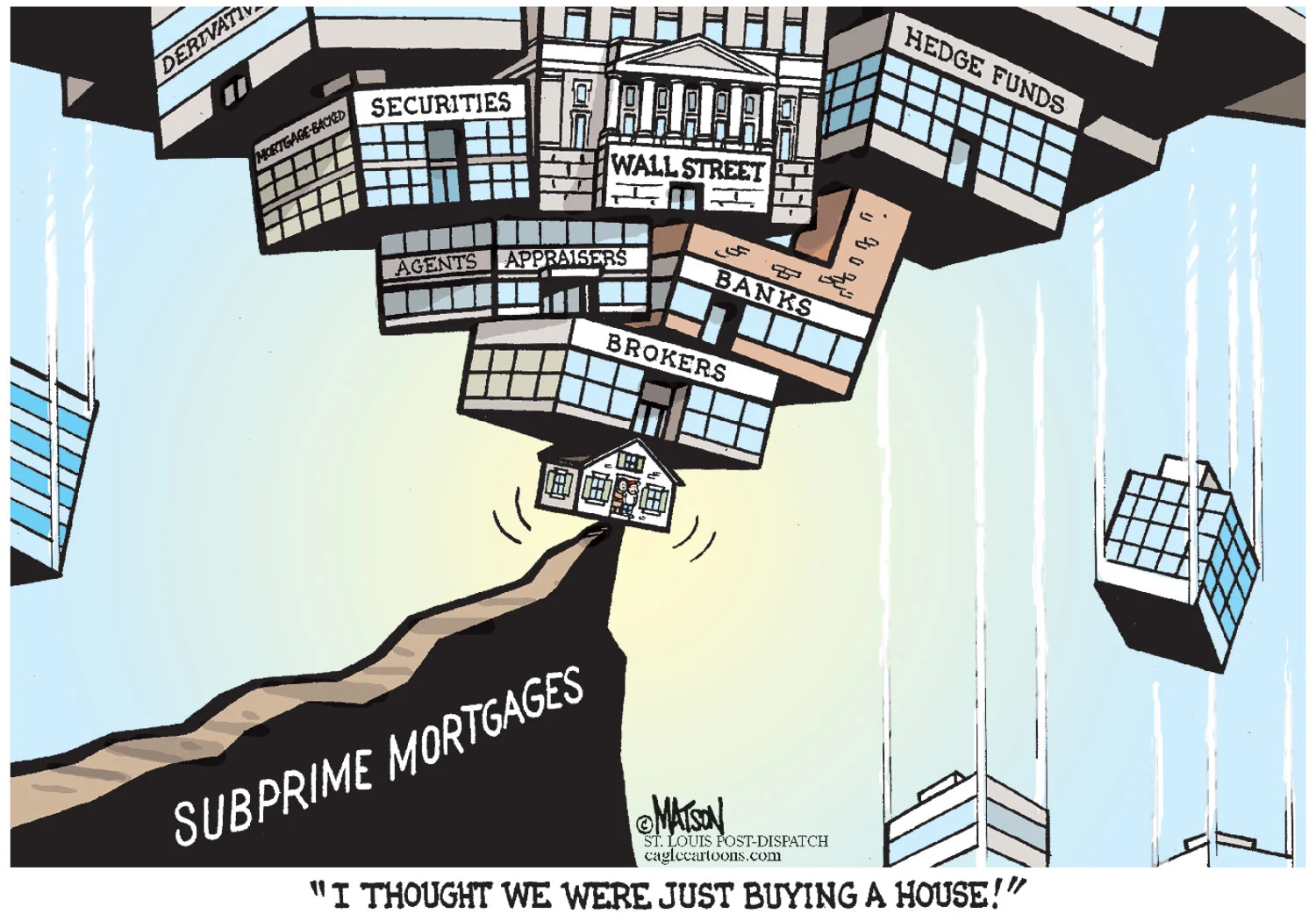

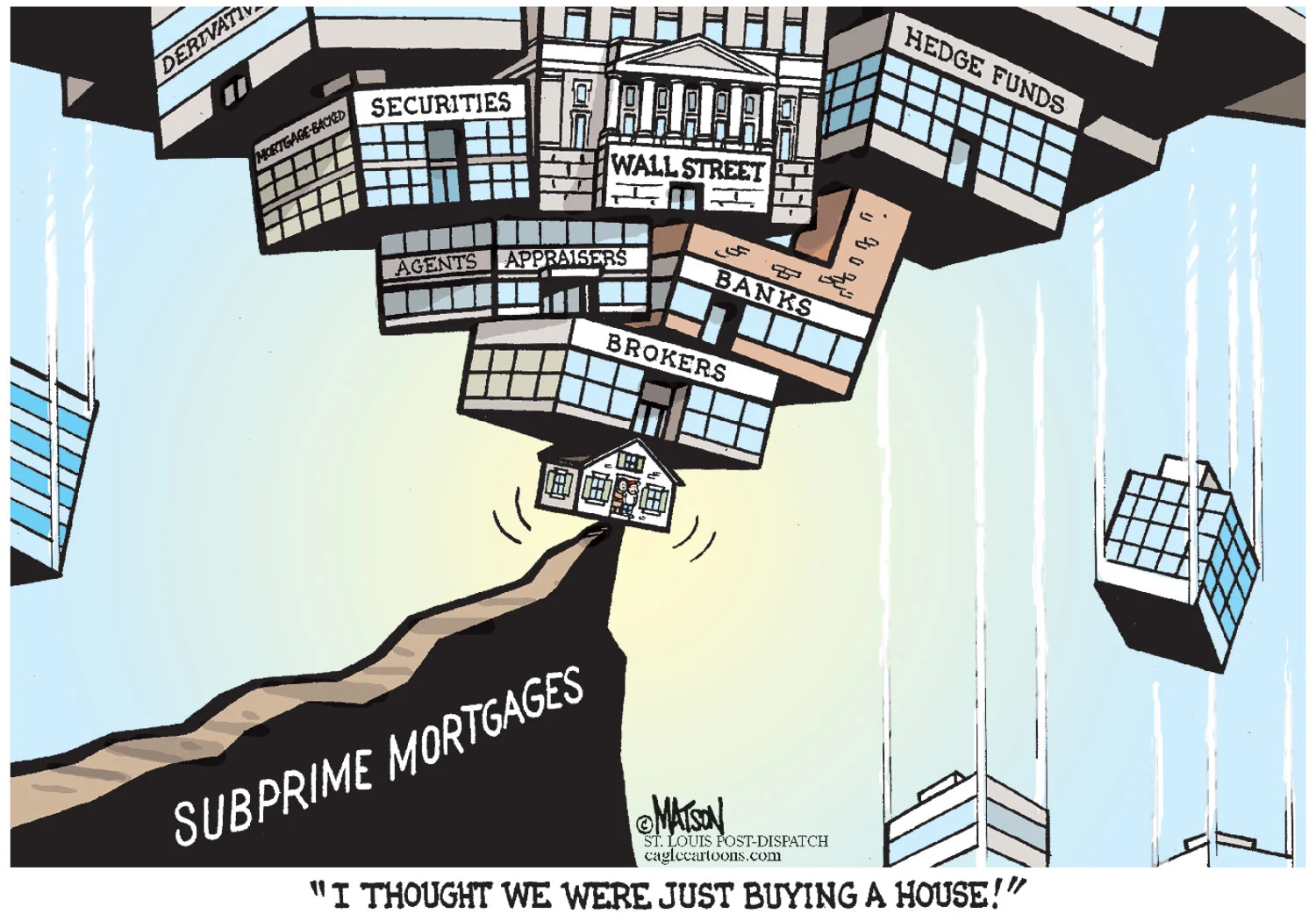

"I thought we were just buying a house!" R.J. Matson Editorial Cartoon. Courtesy of CagleCartoons.com.

Lehman Brothers Building, September 15, 2008. Photo by Nicolas Roberts/AFP/Getty Images.

"I thought we were just buying a house!" R.J. Matson Editorial Cartoon. Courtesy of CagleCartoons.com.

Lehman Brothers Building, September 15, 2008. Photo by Nicolas Roberts/AFP/Getty Images.

Lehman Brothers sign taken into Auction House in London, September 24, 2010. Courtesy of AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth.

Lehman Brothers Building, September 15, 2008. Photo by Nicolas Roberts/AFP/Getty Images.

Lehman Brothers sign taken into Auction House in London, September 24, 2010. Courtesy of AP Photo/Kirsty Wigglesworth.

"I thought we were just buying a house!" R.J. Matson Editorial Cartoon. Courtesy of CagleCartoons.com.

In the mortgage securitization process, a borrower takes out a loan from a lending institution. The lending institution sells the mortgage to intermediaries, such as investment banks, that package the mortgages into mortgage-backed securities (MBS). MBSs were divided into tranches (levels of risk) and bundled with other kinds of securities into Collateralized Debt Obligations (CDO). Both the MBSs and the CDOs received ratings issued by Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, or Fitch. (2)

MBSs and CDOs are sold to investors all over the world, including pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds, hedge funds, and other investment banks. (3) Investors can hedge their CDO or MBS exposure through credit default swaps issued by insurers or broker dealers which cover losses if borrowers default on their loans. Investors, including investments banks, can also purchase credit default swaps on CDOs or MBSs they do not own and receive money if the securities incur losses.

Subprime mortgages, which became popular in the 1990s, were loans offered to borrowers with low credit ratings. In the 2000s, the Federal Reserve’s low interest rates along with legislation such as the 2003 American Dream Downpayment Assistance Act fueled a significant increase in mortgage debt, resulting in a major housing boom and rise in house prices. Risky lending practices involved rating agencies that applied AAA ratings to subprime loans for which little documentation was required from the borrower. Lehman Brothers and other investment banks became heavily invested in MBSs and CDOs that yielded high relative returns. At the same time, wages for the average American remained stagnant. By 2007, declining home prices and rising rates on adjustable rate mortgages triggered a wave of foreclosures, causing devastation to millions of Americans.

Firms like Lehman Brothers pursued an aggressive strategy of borrowing from the capital market at low rates and investing in mortgage-backed securities (MBS) and other speculative securities (including commercial MBSs, high yield debt, and leveraged loans) with the expectation of receiving a higher rate of return. When the MBSs and speculative fixed income securities began to plummet in value, the firm owed more than its assets were worth. “Lehman had broken two basic investment rules: it bought at the top of the market and it failed to diversify its bets,” Mark T. Williams writes in Uncontrolled Risk. “Commercial real estate became a millstone around Lehman’s neck.” (4)

The market for MBSs continued to fold in on itself, leaving investment banks with worthless assets. In “How Securitization Concentrated Risk,” authors Viral V. Acharya and Matthew W. Richardson explain: “Standing behind the collapse of the investment banks . . . was the systematic failure of the securitization market; which had, in turn, been triggered by the popping of the overall housing bubble; which had, in turn, been fueled by the ability of these firms, as well as commercial banks, to finance so many mortgages in the first place.” (5)

One of the early indicators of the falling house of cards was the collapse in the summer of 2007 of two Bear Stearns hedge funds that had major investments in MBSs. Regarding Lehman Brothers, Erin Callan Montella argues, “We were the smallest remaining investment bank. The least diversified. The most vulnerable to a deteriorating fixed income market.” (6) Despite these warning signs, the firm continued its aggressive growth strategy. Another dire sign of the state of the financial system occurred on September 7, 2008, when the government placed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, two government-sponsored mortgage lenders, in conservatorship.

In the fall of 2008, overleveraged in subprime mortgages, commercial mortgages, high yield securities, and leveraged loans, Lehman Brothers faced the prospect of bankruptcy. CEO Richard Fuld proved unsuccessful in securing a rescue effort for Lehman Brothers with the Korea Development Bank, Barclays, or Bank of America. While the Federal Reserve Bank of New York had issued a $30 billion emergency loan to JPMorgan Chase & Company to buy Bear Stearns in March 2008, the government refused to extend additional credit to Lehman Brothers.

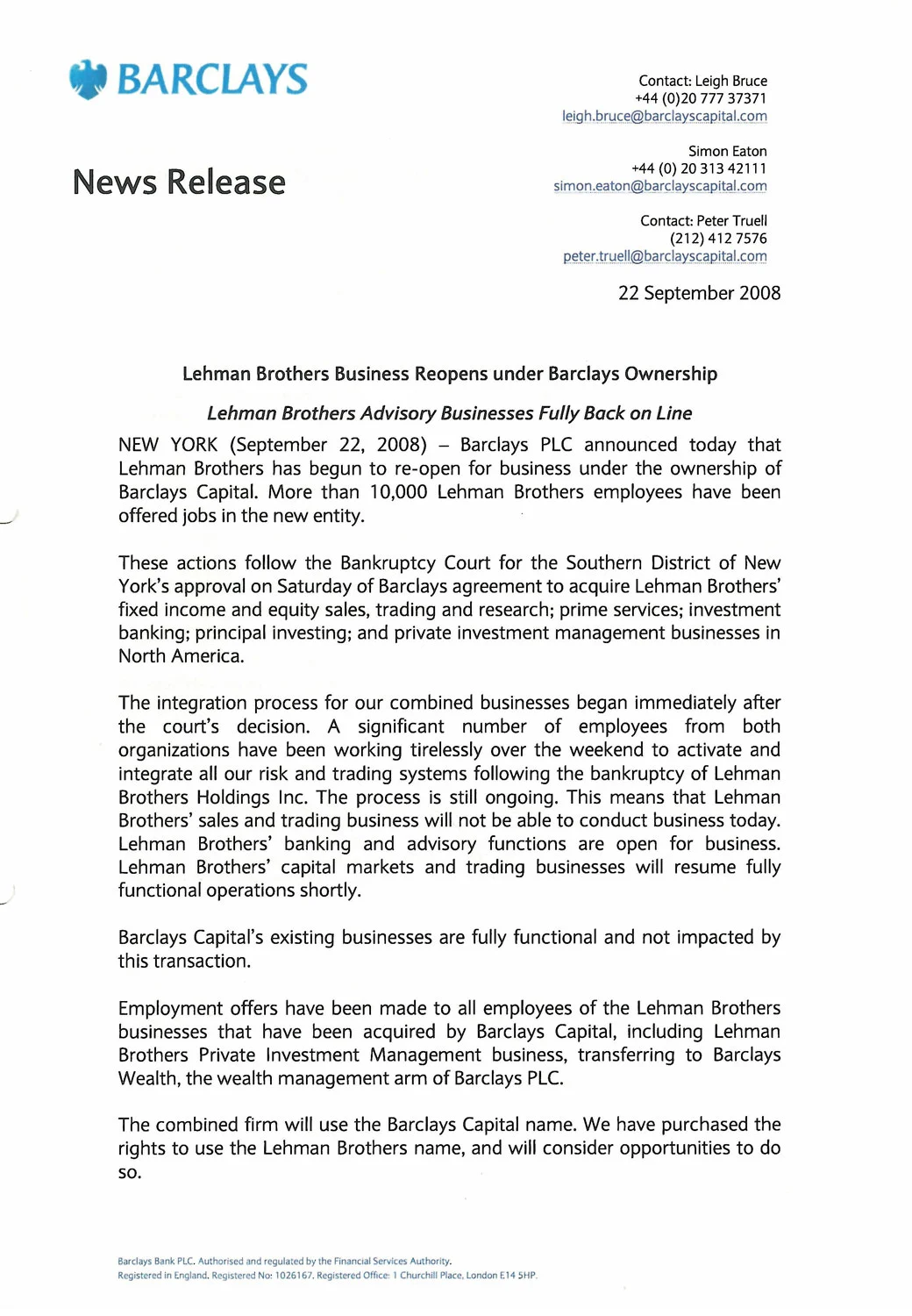

On the weekend of September 13 and 14, 2008, Hank Paulson, Secretary of the Treasury and former CEO of Goldman Sachs, and Timothy Geithner, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, called a meeting of the leading investment banks, which were facing solvency issues of their own, to consider a private-sector rescue plan for Lehman Brothers. That weekend, Bank of America announced it would acquire Merrill-Lynch. By Monday, September 15, 2008, with no buyer, Lehman Brothers, whose stock had plunged over 90 percent since February 2007, declared bankruptcy. That day the Dow Jones fell 504 points. Within the week, Barclays agreed to buy Lehman Brothers’ U.S. large fixed-income operations (that paid a fixed rate of return on a fixed schedule) but not its toxic real estate assets, and Nomura announced its purchase of the firm’s Asian and European operations.

Barclays Group. Press Release, September 22, 2008. Barclays Group Archives.

View as PDF

Barclays Group. Press Release, September 22, 2008. Barclays Group Archives.

View as PDF

Erin Callan Montella, Full Circle: A Memoir of Leaning in Too Far and the Journey Back (Sanibel, FL: Temple Press, 2016), 142. Montella resigned from Lehman Brothers in June 2008.

MBSs were divided into approximately 18 tranches comprised of “AAA” tranches for approximately 75% of the pool, followed by “AA”, “A”, “BBB”, “B”, and equity tranches, with each tranch subordinate to all the senior tranches. CDOs were typically comprised of “BBB” tranches from approximately 100 different MBS securities and were also divided into similar type tranches as the MBSs.

In general, CDOs come in the form of cash CDOs (backed by assets such as bonds or loans) or synthetic CDOs linked to credit derivatives such as credit default swaps.

Williams, 152.

Viral V. Acharya and Matthew W. Richardson, “How Securitization Concentrated Risk,” in What Caused the Financial Crisis, ed. Jeffrey Friedman (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011), 198.

Montella, 158.