The Art of American Advertising:

Trade Catalogs

“The contents of a catalogue . . . must tell their story in about the same way as the well-posted salesman would orally present the advantages of the goods.”Fowlers Publicity Encyclopedia, 189713

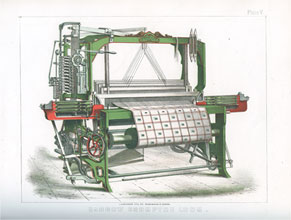

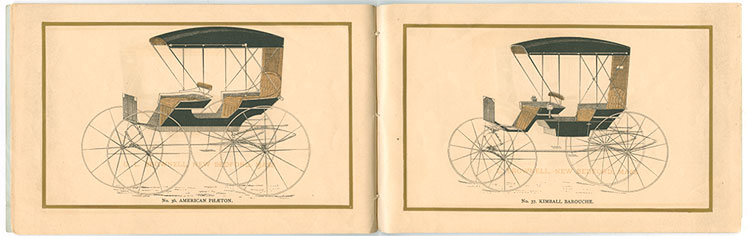

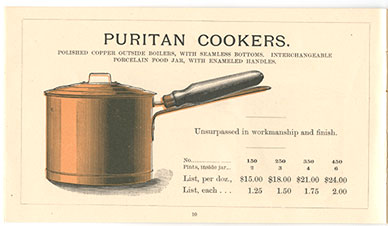

Various advertising formats offered distinct means of communication and distribution to a mass audience. Trade catalogs, for example, became an integral way of merchandising new industrial products created from the enormous factory output and market demands of the industrial revolution. Comprised of multi-page listings, catalogs included stock numbers, prices, and in some cases extensive descriptions, testimonials, instructions for use, short company histories, and illustrations (both woodcuts and lithographs) of products and designs. Catalogs ranged in size from simple pamphlets to encyclopedic tomes and sometimes contained samples of particular products such as fabric swatches or small sheets of wallpaper.

A corps of traveling salesmen, known as “drummers,” circulated trade catalogs to potential customers along with product samples.14 Trade catalogs were also distributed by mail and in some cases came to take the place of salesmen. “Numbers of firms selling at wholesale . . . have discarded traveling salesmen altogether and are now selling by catalogue,” Sidney Sherman noted in his 1900 study of advertising in the United States.15

Trade catalogs helped businesses to stay competitive by introducing them to the latest technological innovations that improved the efficiency and speed of work in agriculture, manufacturing, communications, and transportation as well as advances in newly developing fields in science and medicine. From agricultural catalogs, for example, farmers learned about patented improvements in reapers, threshers, and harvesters that could significantly increase grain output.

The growth of registered patents from several thousand a year in the mid 1800s to over 50,000 a year by the end of the century was indicative of the explosion of new products. Trade catalogs featured goods of major industries as well as of a variety of supporting industries that produced items such as tools, dies, and electrical fixtures. A railroad company could thus reference a range of trade catalogs for its needs—from those representing major manufactures of locomotives and rails as well as those representing smaller manufacturers that produced passenger doors and ticket punches.

The beginnings of a national market, including the rapid rise of department stores and mail order catalog retailers, had tremendous effect on the life of the home consumer as well. Mass-produced durable goods came to supplant items formerly made at home or bought as generic items at the general store. Trade catalogs advertised a wide variety of home goods including sewing machines, stoves, cooking ware, ready-made clothing, shoes, packaged foods, and seed catalogs.

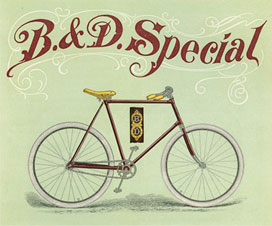

With access to time-saving home consumer goods, decreased hours in the workweek, and the rise in per capita income, more Americans now had the time and money to enjoy leisure activities once considered the privilege of the upper class. The Progressive Era of social activism and political reform from the 1890s to the 1920s also encouraged the pursuit of leisure activities to combat the fatigue and monotony of factory work. Trade catalogs advertised the wares of emerging industries devoted to sports, hobbies, and entertainment activities, promoting products from toys and musical instruments to cameras and tennis rackets.

Journals for the printing trade, including Profitable Advertising, Printers’ Ink, and the Inland Printer, offered advice on designing trade catalogs that were both informative and inviting. Fowlers Publicity Encyclopedia provided such guidelines as: “Do not crowd matter, Good-sized type, wide margins, and plenty of paragraphs strengthen the catalog” and “If the catalogue is descriptive and for the masses, try its contents on a dozen or so of the common people, and see that they understand it.”16 In contrast to brief ads in periodicals or newspapers created to pique consumers’ interest, trade catalogs were designed to provide as complete information as possible about the universe of a manufacturer’s goods.

13 Nathaniel Clark Fowler, Fowlers Publicity Encyclopedia. Chicago: Publicity Publishing Company, 1897, vol. I, “Catalogues,” chap. XXII.

14“Drummers” were so named for salesmen who “drummed” up business and sometimes used drums to attract attention.

15 Sidney A. Sherman, “Advertising in the United States,” Publications of the American Statistical Association, vol. 7, no. 52 (December 1900): 124. The rise of department stores and mail order companies like Montgomery Ward and Sears Roebuck also reduced the need for traveling salesmen.

16 Fowler, Fowlers Publicity Encyclopedia, vol. I, “Catalogues,” chap. XXII.