The Art of American Advertising:

Souvenirs & Novelties

“The province of the advertising novelty is to present to the customer . . . something of a tangible or more or less permanent value.”Fowler’s Publicity Encyclopedia, 189723

Souvenir items and publications that customers could repeatedly use and reference proved another effective way to keep a product’s name in the mind of the consumer. Business cards, postcards, holiday greeting cards, and books of songs, recipes, or medical advice, all created for “gratuitous distribution” by advertisers, had an extended life. “Salesmen . . . helped establish brand familiarity by putting up promotional displays . . . and giving away calendars, glasses, and other items bearing company slogans and trademarks,” business historian Walter Friedman explains.24 For example, calendars (produced as folded cards, booklets, or wall hangings) assured businesses of prominent visibility for an entire year.

By the mid 1800s, almanacs, filled with practical information from gardening tips to postal rates, became an especially successful advertising venue for patent medicines. 25 Advertisers generally paid for almanacs, allowing publishers to distribute them and local retailers to print their names on them at no cost. James C. Ayer, involved in the pharmaceutical industry, reaped enormous publicity benefits from the distribution of yearly almanacs. Ayer eventually established his own lithograph and printing department that issued millions of almanacs annually.

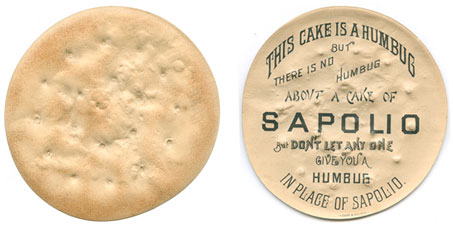

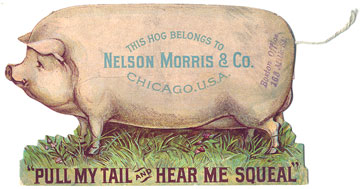

Advertisers took another creative leap with the production of novelty items, the precursors to bubble gum cards, Cracker Jack Toys, and other souvenir collectibles of the twentieth century. Offshoots of trade cards and souvenir publications, novelties included mock items made in the size and shape of an advertised product. Flaps, pullout levers, and projecting tabs, known as “mechanicals,” created animations often to humorous effects—such as a man moving his mouth as he enjoys Snider’s Catsup or a Nelson Morris & Co. pig inviting customers to “Pull my tail and hear me squeal.” Advertisers also produced miniature replicas of their products. Heinz, for example, dreamed up the idea of pickle-shaped pins along with the slogan “57 varieties,” which were featured at the 1893 Chicago World’s Columbian Exposition.26

Many businesses printed their company names onto foldout fans, another popular advertising giveaway, and advertisers tapped into the growing toy industry with booklets of cutout paper dolls and images overlaid with tracing paper. Bookmarks appeared in beautifully chromolithographed designs, and other novelties such as rulers stamped with company names offered the potential of continued visibility. Cultural historian Maurice Richards notes, “By the end of the 19th century few stones in the field of advertising novelty had been left unturned.”27

23 Fowlers Publicity Encyclopedia. Volume II, “Novelties,” Chapter XXIV.

24 Friedman, p. 99.

25 Advertising expenditures for patented medicines ran particularly high at a time when little was understood about sickness and infectious disease.

26 Friedman, p. 101.

27 Richards, p 9.