Photography and Print Advertising

Photography became established in print advertising in the late 1800s after perfection of the halftone process allowed photographs to be printed alongside text. Straightforward shots of consumer products filled the back pages of magazines. Studio photography, however, was an expensive enterprise, and before World War I magazine and newspaper publishers tended to favor drawn illustrations over photographs.

In the 1920s, the tremendous increase in industrial output and consumer demand led executives to look for ways to make their company’s products stand out among the vast array of manufactured goods. As Elspeth Brown notes in The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture 1884–1929 (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), at that time “the influence of applied psychology had reoriented managers toward an appreciation of the mind as the critical element of rationalized consumption. Greater sales in an increasingly competitive and national marketplace required persuading reticent consumers that individual difference and personal meaning could be theirs despite a regularized landscape of standardized goods.”2

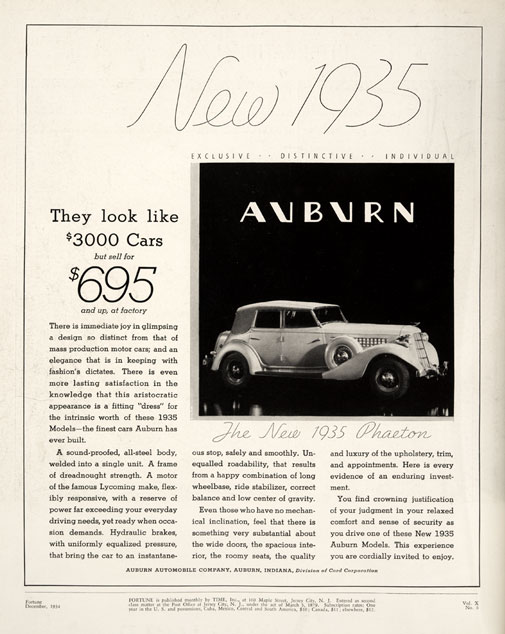

Journals like Abel’s Photographic Weekly, Commercial Photographer, and American Photographer promoted photography as a medium of enormous potential to advertisers. Buyers “believe what the camera tells them because they know that nothing tells the truth so well,” asserted the Photographers Association of America.3 Photographs like Gilbert Seehausen’s striking before-and-after shots attesting to the benefits of Lady Esther face powder offered persuasive realism that appealed to customers on an emotional level.4 By the 1930s, photography would become the medium of choice for most print advertising.

- Elspeth H. Brown, The Corporate Eye: Photography and the Rationalization of American Commercial Culture 1884–1929. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005, p. 160.

- Photographers’ Association of America in Roland Marchand, Advertising the American Dream: Making Way for Modernity, 1920–1940. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1985, p. 150.

- Elspeth Brown notes that “pictorialism’s aesthetic ideals were not inherently antithetical to commercial considerations” and advertisers used soft-focus photographs by artists like Lejaren à Hiller before modernist images came into fashion in the late 1920s and 1930s. See Brown, note 2, p. 177.