1837: The Hard Times

Historians have traditionally attributed the Panic of 1837 to a real estate bubble and erratic American banking policy.1 Most speculation concerned western land opened to settlement after Indian removals, but northeastern forests were among the most overvalued holdings. One contemporary observed, “The speculation in Maine timber lands was the first in order, the most extravagant and irrational, and the most ruinous to those engaged in it.”2 In Massachusetts, Nahant Bank and Boston’s Oriental Bank fell victim to this speculative fever when their assets became dangerously concentrated in unimproved Maine land far from navigable waterways. An 1838 survey confirmed that this property was grossly overvalued and both banks failed.3

Developments in banking compounded the crisis. The money supply swelled when the Bank of the United States lost its charter and each of the nation’s 850 banks could again issue banknotes (a private form of currency) with little restraint. This paper money then depreciated rapidly when President Jackson’s Specie Circular of 1836 mandated payment for government land in gold or silver. Ten months later banks refused to redeem their notes in specie, bringing commerce to a standstill. New England escaped the worst of the crisis thanks to Boston’s conservative banking establishment, which, led by the Suffolk Bank, curbed the excesses of the rural banks.4

The 1837 crisis and the six-year depression that followed had lasting effects on the American economy. The credit ratings industry, for example, has its origins in the hard times of the late 1830s and early 1840s. So many businesses failed that Lewis Tappan, a prominent opponent of slavery, founded a company that offered subscribers up-to-date and comprehensive credit information on the businesses in their communities. Tappan’s firm, the Mercantile Agency, built on his abolitionist connections to create a nationwide network of credit reporters that was the direct predecessor of today’s credit ratings firms.5

The effects of the Panic of 1837 also were felt far from home. Global trade with China factored into—and was transformed by—the crisis. Rapid credit expansion and avid speculation in tea, silk, and other products of the Celestial Empire contributed to the failure of merchant houses from London to New York and Boston in the late 1830s. In the aftermath of the crisis, many New England traders like J. P. Cushing redirected their capital from the China trade to American railroads.6

- Bray Hammond, Banks and Politics in America: From the Revolution to the Civil War (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1957), pp. 451–499; Peter Temin, The Jacksonian Economy (New York: Norton, 1969).↖

- Richard Hildreth, Banks, Banking, and Paper Currencies (Boston: Whipple & Damrell, 1840), p. 91.↖

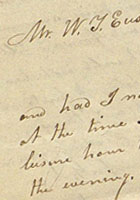

- H. A. Boardman to W. T. Eustis, Jan. 15, 1838. Oriental Bank (Boston, Mass.) and Nahant Bank (Lynn, Mass.) Records. Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.↖

- David Rice Whitney, The Suffolk Bank (Boston: Privately printed, 1878).↖

- James D. Norris, R. G. Dun & Co., 1841–1900: The Development of Credit Reporting in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Greenwood Press, 1978), p. 8.↖

- W. E. Cheong, “China Agencies and the Anglo-American Financial Crisis, 1834–1837,” Revue Internationale d'Histoire de la Banque 9 (1974): 134–159; Arthur M. Johnson and Barry E. Supple, Boston Capitalists and Western Railroads: A Study in the Nineteenth-Century Railroad Investment Process (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1967), pp. 24–32.↖