I'm in a winter coat and hat in the January pre-dawn cold and dark, standing on sandbags on a riverbank in the middle of Uttar Pradesh, India. Pilgrims and the faithful and the respectful come to the river this morning by the hundreds, clad in the minimum, praying and splashing and releasing marigold wreaths and rafts of small oil lamps into the river. This is not like any field research I've done before.

Thirty-five Harvard colleagues and I are at the Kumbh Mela in Allahabad, India, a mass pilgrimage in which tens of millions of Hindus gather to bathe at the confluence of the sacred Ganga (Ganges) River, the Yamuna River, and the mythical underground Saraswathi. Legend says that on his return to the Himalaya, Vishnu flew over this spot and dropped sacred nectar from a pitcher—a kumbh.

We are all here to witness how devotion, design, health, and finance come together.

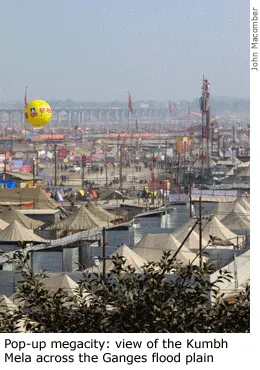

Six months ago this land was under 30 feet of water. Three weeks from now this will become the largest city on earth, the largest single-purpose gathering of humanity in history. Every 12 years, when the moon and stars are aligned, this becomes the most auspicious spot in Hinduism, and there is a six-week-long festival, or mela, for the millions of pilgrims. The Maha Kumbh Mela is happening right now. It's expected to draw close to 200 million people over almost eight weeks, and as many as 30 million in a single day. The Harvard team is here to learn about why and how.

Our team is led by Prof. Diana Eck of the Harvard Divinity School. She is a world expert on pilgrimages and the author of definitive books about the rivers of India. Prof. Rahul Mehrotra, chair of the department of urban planning and design at the Harvard Design School, has a team on site mapping and photographing the city that has sprung up here. Prof. Greg Greenough of the Harvard School of Public Health is directing researchers interested in everything from the pH of the Ganga to the quality and quantity of toilets to the structure of the medical response teams in place; after all, from time immemorial pilgrimages have been perfect places to transfer and share not only information, but disease as well. From Harvard Business School, I am here to discover what the Kumbh Mela can teach me about real estate, urbanization, sustainability, and infrastructure. We are all here to witness how devotion, design, health, and finance come together.

You hear the Mela before you see it. I had expected serenity, sanctuary, devotion. What I experience instead is a nonstop cacophony as each of the major Akharas (aligned but competing religious denominations; there are about 17 of them) blasts its own music, prayers, and programs all day and night, with just a slight pause from about 11 pm to 3 am. You smell the Mela before you see it—a combination of wood smoke and dust. And to see it is like nothing I've witnessed—and I've done field research in cities from Vietnam to Peru to China to Saudi Arabia and in five states in India.

The popular press focuses on the colorful: the globally known swamis; the ash covered monks; the business people and penniless people together in the Ganga; the elephants and orange robes and crazy hair and the blend of true believers and true hucksters. There are photo-essays galore all over the world-wide web. But there is much more to the Mela than shahi snaan and naga sadhus (sacred dips and naked ascetics).

I'm here to see if the lessons of a pop-up megacity , built around a duodenary pilgrimage, are lessons we can extend to the building of other new cities. I believe there are three global trends that will drive much of the global conversation of the next 30 years. First, rapid and massive urbanization: hundreds of millions of people are migrating to cities for better lives. Second, worsening scarcity of critical resources like clean water, clean air, electric power, and land (and increasing oversupply of traffic, pollution, and greenhouse gases). And third, government logjams: federal governments are stuck and can't take long term action on these problems—stuck in the US or India over politics and stuck in China and South Africa over funding.

The sandbank below me is a proxy for many new cities that need to be built in India and throughout Asia, Africa, and South America; the research will draw from our observations of how these lessons fit in the framework of infrastructure and urbanization.

I'm here to look at the roads, the pedestrian corrals, the water, the sanitation, the provision of electricity, the thoughtful deployment of public-private partnerships, and the land allocation necessary to support up to 200 million pilgrims. There are extensible leadership and finance lessons for me here, and they can become Finance and Strategy teaching material. We can think of decision points, analytical skills, and universal frameworks that we can apply to HBS style case studies—the core of participant-centered learning in our MBA and Executive Education programs.

The people who planned this pop-up city had to wait until the monsoon receded to assess the banks. They needed to understand how many hectares each Akhara required. (The Juna Akhara, the biggest, has four separate quadrants.) They had to figure out how to provide on the order of 30 MVa of power to 22,000 temporary poles (provided by a bank of diesel generators out of sight of the main event, supplementing the state grid), not to mention designing a route to the river, into the river, and out of the river for millions of pilgrims. There are said to be more than 156 kilometers of double track checker plate steel creating drivable roads in the sand and more than 4,000 hollow steel floating pontoons supporting 18 temporary bridges spanning the Ganga and Yamuna.

We are witnessing back-of-house success in administration that leads to front-of-house success in the experience for more than a hundred million pilgrims. This event is a big deal for the Republic of India and for the state of Uttar Pradesh and for the city of Allahabad. It needs to go well.