Microaggressions happen in the workplace all the time: A White worker might ask a Hispanic colleague how they learned to speak English so well, or a man might casually refer to women in the office as “girls.” But these interactions can be damaging.

“The person saying these things might not know they’ve done anything wrong,” says Summer Jackson, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School. “But for the recipient, it’s like a lightning bolt that calls into question their social identity, makes them feel subordinate, and makes them wonder, ‘How could this person say this to me?’”

The person saying these things might not know they’ve done anything wrong.

Microaggressions—which are seemingly innocuous statements made by a person holding a dominant social identity toward another person with a marginalized social identity—come across as insensitive and can sever relationships if they’re not properly addressed. Jackson provides advice for how to repair the damage in the Academy of Management Review article “It Takes Two to Untangle: Illuminating How and Why Some Workplace Relationships Adapt While Others Deteriorate After a Workplace Microaggression,” coauthored with Basima Tewfik of the MIT Sloan School of Management.

In a workplace climate where retention and job satisfaction are under pressure, addressing microaggressions effectively can strengthen trust and improve team performance, Jackson says. While previous studies of microaggressions have focused on the damage to workplace culture, Jackson and Tewfik offer a framework for turning potentially destructive incidents into opportunities to form stronger connections.

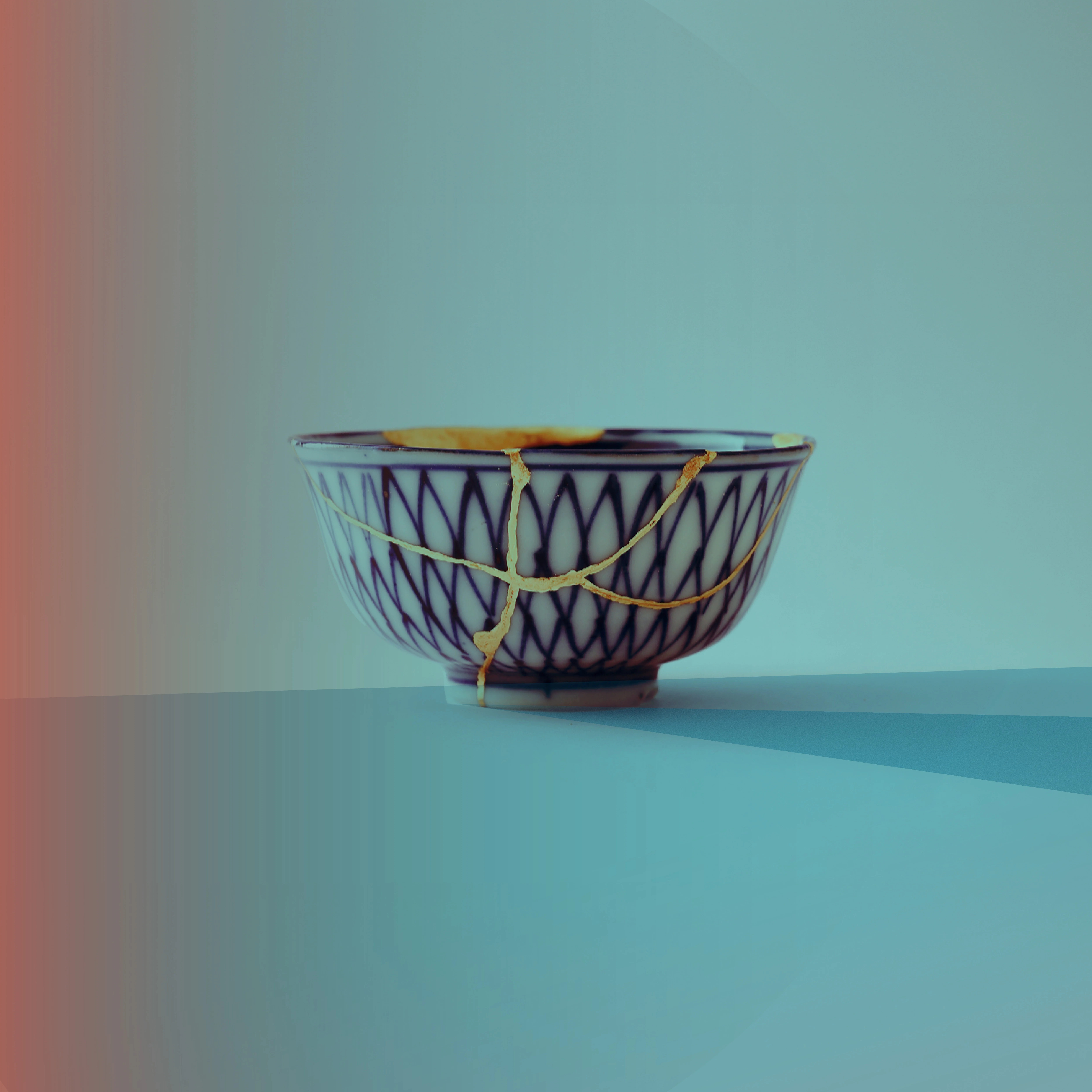

“We wanted to unpack what happens after a microaggression and see if there’s a way people can get to a place of not just bringing the relationship back to the status quo, but make it stronger,” Jackson says. When discussing her research, Jackson notes that others have drawn comparisons between the healing process outlined in the paper and kintsugi, a Japanese art form that repairs broken pottery with a golden lacquer, making it even more beautiful than before.

Handling a microaggression

Microaggressions may not be as overt as more blatant racial or sexual discrimination, but they can still kick off the body’s “fight or flight” mechanism. Left unaddressed, repeated microaggressions can cause chronic stress, hurt team morale, and push employees to quit.

However, these incidents don’t have to destroy relationships. With introspection and open communication, colleagues can mend the rift and forge more authentic and trusting relationships, say Jackson and Tewfik.

Since microaggressions are often unintentional, repair must start with the recipient, says Jackson. “You have to move out of the ‘fight or flight’ reaction into curiosity,” Jackson says. “Yes, protect yourself in the moment, but then reflect on whether the relationship is worth preserving.”

To do that, she says, recipients of microaggressions should evaluate the relationship based on these factors:

Interaction history. How much have they seen the other person positively value an equitable culture in the workplace?

Relational closeness. How close and connected did they feel toward the other person before the incident?

Relational viability. How likely are they to work with this person in the future?

Answering those questions can help the recipient assess the importance of repairing the relationship and determine whether the person who made the microaggression is willing to address the incident.

“Do you feel like this is someone who genuinely cares about you and your well-being?” Jackson asks. “If so, you can start to move into an inquiry phase.”

The next step, she says, is approaching the person with a clear explanation that focuses on the behavior and feelings, rather than attacking the person’s character. “You might say, ‘When you said X, it made me feel Y. And it made me wonder if you see me the same way you see others on the team.’”

Repairing the relationship

Once the recipient honestly shares their perspective, Jackson says, it’s up to the person who made the remark to go through similar introspection. After all, the person is likely to feel uncomfortable, and the knee-jerk reaction may be to defend or justify the behavior.

“It can be confusing to someone who may not realize how their comment would be interpreted,” Jackson says. “Most people like to think they are good people, and so it can cause a threat to someone’s self-image.”

She suggests that the person accused of the microaggression also try to move past their initial “fight or flight” response and similarly evaluate the closeness of the relationship, realizing that the other person isn’t raising the incident flippantly. While an apology or reassurance of intent can be helpful, that’s not nearly as powerful as a sincere desire to understand.

“You can say, ‘I didn’t realize it landed that way. Help me understand,’” Jackson says.

What managers can do

Managers can also help heal workplace relationships suffering from microaggressions. Sometimes, it’s effective to avoid confrontation in the moment and instead approach the situation later with curiosity and deference.

“If you try to intervene in the moment, it can escalate the situation,” Jackson says. “Whereas if you meet the person later, you can ask, ‘I noticed in the meeting that you reacted to so-and-so’s behavior. What was going on then, and how can I help?’”

While such conversations aren’t easy, they can lead to breakthroughs in restoring and transforming relationships, Jackson says, and even unleash openness, creativity, and collaboration.

“When people feel like they can bring their whole selves to work, they have a better sense of belonging and connectivity to the organization,” she says. “It’s no longer a ‘clash of realities,’ but you actually come to see one another’s realities better and accept one another on a deeper level.”

When people feel like they can bring their whole selves to work, they have a better sense of belonging and connectivity to the organization.

Despite people’s best intentions, she notes, it’s unrealistic to expect that microaggressions won’t happen at work. Cultural blind spots and implicit beliefs inevitably cause people to unwittingly say offensive things to others.

“It’s really hard to know how people’s social identities are going to be salient to them and all the different historical stereotypes that might be associated with them,” Jackson says. Instead of emphasizing prevention, she recommends that managers focus on normalizing open conversations and repairing relationships.

“It’s a real opportunity to learn something new about another person and incorporate that understanding into your own ability to be a better colleague,” Jackson says.

Image by Ariana Cohen-Halberstam with asset from AdobeStock/Marco Montalti

Have feedback for us?

It Takes Two to Untangle: Illuminating How and Why Some Workplace Relationships Adapt While Others Deteriorate After a Workplace Microaggression

Jackson, Summer R., and Basima A. Tewfik. "It Takes Two to Untangle: Illuminating How and Why Some Workplace Relationships Adapt While Others Deteriorate After a Workplace Microaggression." Academy of Management Review (forthcoming). (Pre-published online March 10, 2025.)