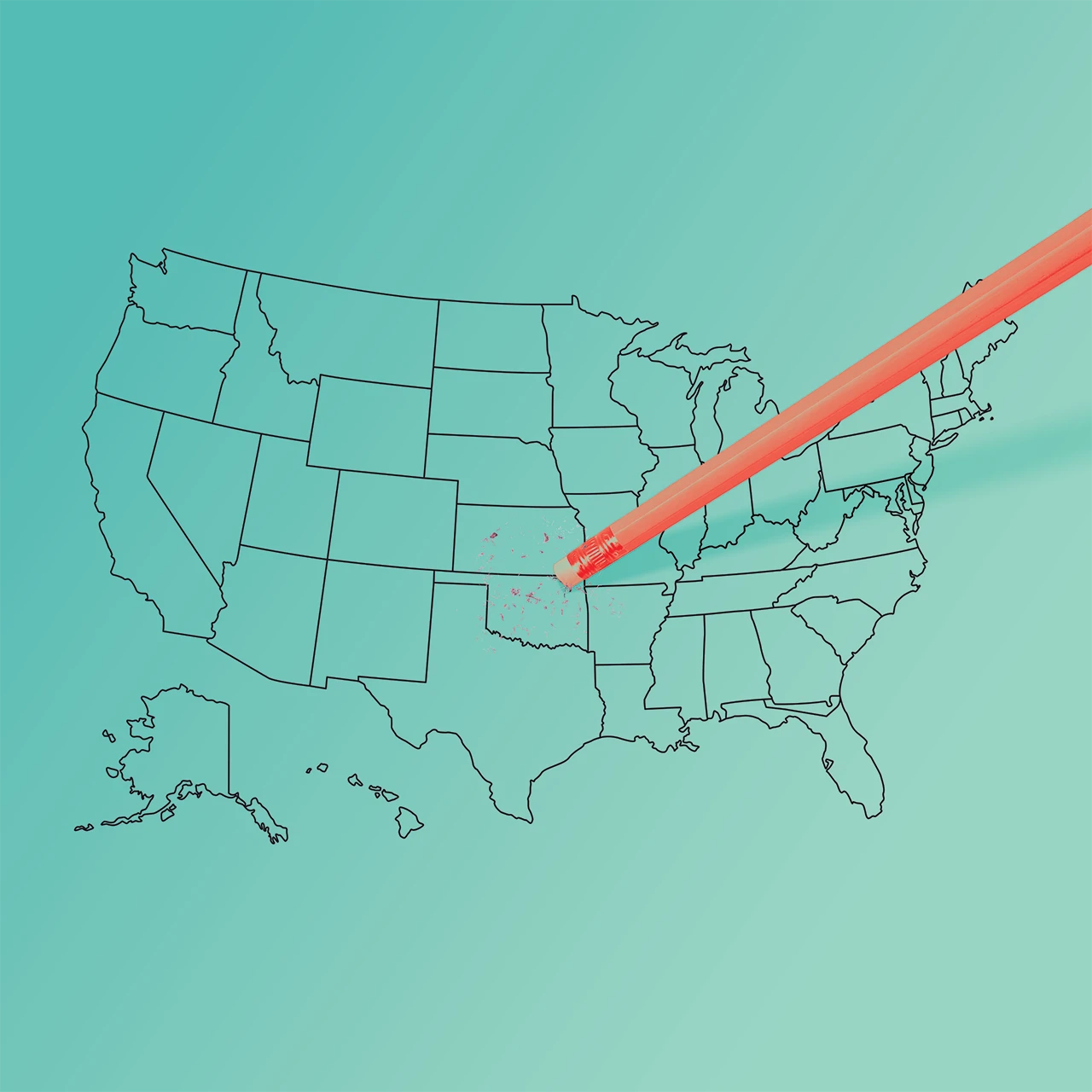

Redistricting controversies like those in Texas and California aren’t just political battles. Changing boundaries of US House seats can disrupt carefully crafted relationships between lawmakers and constituent businesses.

When redistricting shifts representation, lawmakers turn to SEC filings to research unfamiliar businesses in their new districts. Meanwhile, companies that find themselves with new representatives step up lobbying efforts with those lawmakers, says research by Harvard Business School Associate Professor Ethan Rouen.

Described as an “early dance,” the two sides study each other through public and private channels, including Securities and Exchange Commission filings, corporate reports, and legislative lobbying records.

“What’s surprising is the multiple avenues through which politicians and businesses try to learn more about each other,” says Ethan Rouen, the Terrie F. and Bradley M. Bloom Associate Professor of Business Administration. “What’s also surprising is how quickly it all starts after redistricting. They are communicating and reacting to one another.”

Any sudden changes to House districts, a potential outcome from redistricting battles in Texas and California, can disrupt lawmaker-constituent relationships that took years to establish.

“It’s costly and time-consuming to build these cooperative relationships,” says Rouen.

“Legislators’ Demand for Firms’ Financial Statements: Evidence from US Congressional Redistricting Events” published online in July by the Review of Accounting Studies looks at the relationship-building costs of redistricting. Rouen partnered with Matthew Ma, an assistant professor at Rutgers University—Camden School of Business; Jing Pan, assistant professor at Penn State University’s Smeal College of Business; and Laura Wellman, associate professor at the University of Oregon’s Lundquist College of Business.

Quantifying the early dance

The researchers compiled data related to hundreds of US House members and thousands of publicly traded companies in 37 states that experienced redistricting in 2012, following the 2010 census. Their sources included the SEC, ProPublica Congress, LobbyView, MaxWind, and corporate annual reports.

Researchers compared search activity before- and after-redistricting by congressional staff members seeking firms’ annual and quarterly financial filings to the SEC. They used IP addresses to identify staffers’ district offices.

By the numbers

Congressional staffers sought more information from the SEC after redistricting or before key votes impacting new firms in their districts.

- 15%More annual filing downloads after redistricting

- 11%More quarterly filing downloads after redistricting

- 3%More SEC database searches before roll call votes tied to lobbying

Have feedback for us?

Legislators' Demand for Firms' Financial Statements: Evidence from U.S. Congressional Redistricting Events

Ma, Matthew, Jing Pan, Ethan Rouen, and Laura Wellman. "Legislators' Demand for Firms' Financial Statements: Evidence from U.S. Congressional Redistricting Events." Review of Accounting Studies (forthcoming). (Pre-published online July 7, 2025.)