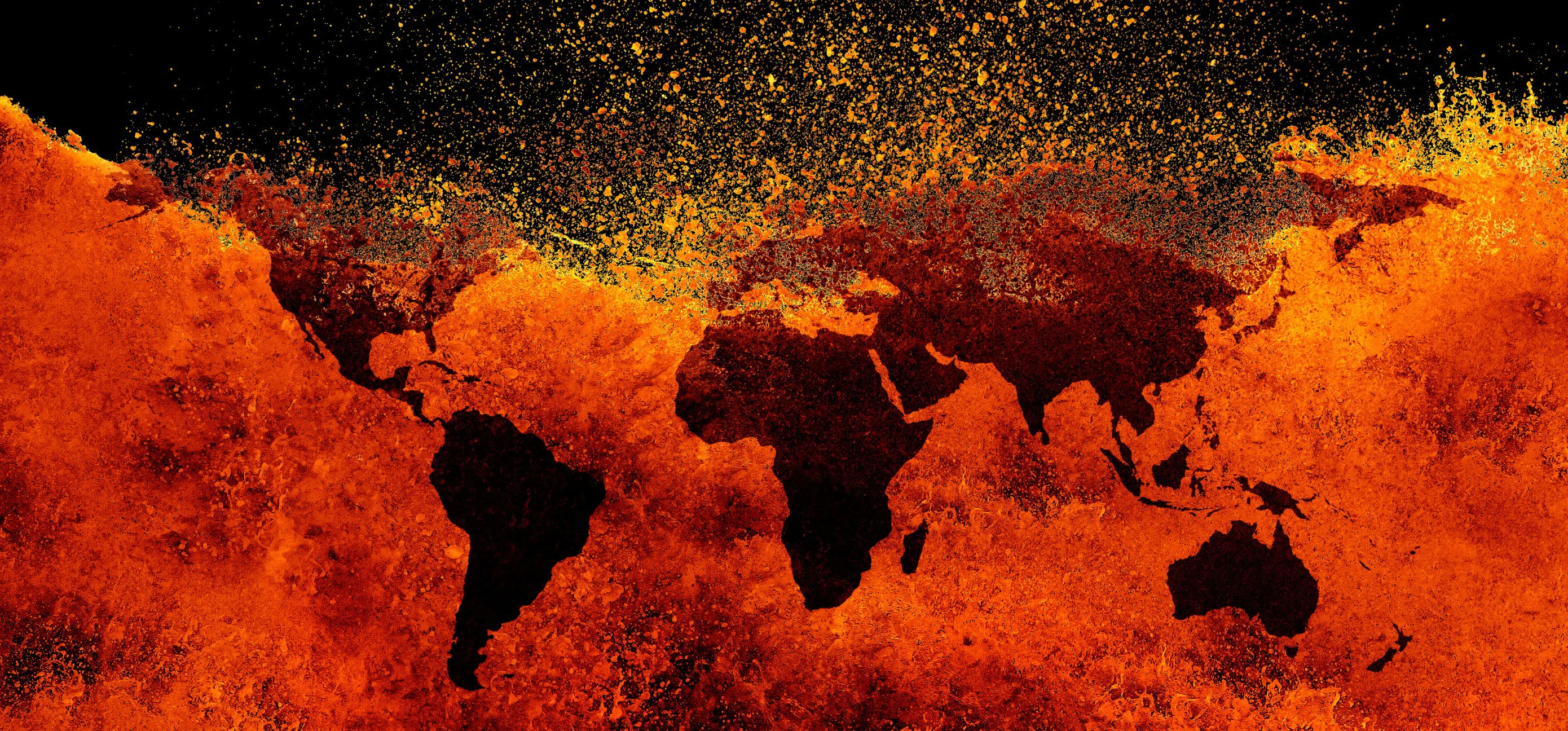

The Earth is burning. We only have a little time to arrest climate change, and if we fail to do so the consequences will be both dire and irreversible. We have the technology and the resources to fix things, if we want to. We even have a business case. It’s in no one’s interest to torch the planet.

Mark Carney, the Governor of the Bank of England, points out that insured losses from extreme weather events have risen five-fold in the last 30 years. He wonders if the financial markets face the risk of a climate “Minsky moment”—a reference to the work of the economist Hyman Minsky, whose analysis was used to show how banks overreached themselves before the 2008 financial crisis. He warns that those companies and industries that failed to adjust to climate change might cease to exist. Jeremy Grantham, the famously successful investor who predicted the 2008 catastrophe, suggests that the failure to acknowledge the risks posed by climate change means that the entire financial system is riding on a carbon “bubble” that will cause havoc when it bursts.

Why have we been so slow to respond? Even the greatest innovation hotbed in the world—Silicon Valley—has been oddly absent on this issue.

Why has it been so hard for us to come together to solve the biggest problem of our time, an existential threat to the survival of our civilization? There are, of course, many answers to this question—but I think that one of the most important is that combating climate change is an innovation problem. That is, it is hard for exactly the same reasons that any really disruptive innovation is hard.

As the storms get stronger and the harvests fail more often, political pressure for carbon regulation will continue to grow.

Let me explain. Incumbent firms have always struggled with disruption. They face three problems: denial, greed, and overload coupled with incompetence.

Denial: It isn’t happening

I like to call this the “crossed fingers” view of the future. Firms desperately want to believe that the future will look something like business as usual, that the regulatory and the market conditions that led to their success will remain the same and will not shift significantly in response to sweeping changes in technology, policy, or consumer preference.

Some oil and gas companies, for example, appear to be betting against a scenario in which emissions remain unregulated and renewables remain expensive, allowing them to continue to dominate the energy business. Nearly everyone else can see that this is no longer the most likely scenario, is it? Renewable energy is already cost competitive in many places—even without subsidies—and will likely only continue to become more competitive in the future. As the storms get stronger and the harvests fail more often, political pressure for carbon regulation will continue to grow.

Greed: It won’t make any money

Another classic problem faced by firms attempting to pivot in the face of disruption is the belief that even if the industry is being disrupted, it doesn’t make financial sense to respond. Current customers simply won’t want it and/or the new stuff often looks less profitable—often is less profitable—than the existing business. Introducing new things is always difficult, and many of the firm’s existing assets may become obsolete. Of course the choice is not between doing the new thing and keeping the existing business. It’s between doing the new thing and going out of business, but in the early stages that’s often hard to see.

You often hear, for example, that holding climate change to the bare minimum will be expensive. It will. But doing something will be a lot less expensive than doing nothing. Left unchecked, climate change will substantially reduce GDP, and potentially destabilize the entire financial system. (Not to mention creating untold suffering for millions of people and pushing much of the natural world to the brink of extinction.) It’s much more useful to think of fixing climate change as a huge market opportunity.

Overload and incompetence: We can’t get it done

Most of the time, companies fail to respond effectively to change because they are deeply overloaded—and because they’ve spent many years getting very good at running the current business. Most people have already promised to do too much—and are under continuous pressure to make their quarterly numbers. Embracing transformation change requires making space for it—and rethinking the deep structure of the company.

The good news is that this is a problem that can be fixed. In Reimagining Capitalism in a World on Fire, I demonstrate how firms that develop a shared pro-social purpose—and that embed it throughout the firm in empowered, high-commitment labor practices—are ideally positioned to drive organizational change. Change is always hard, but if you can persuade your employees that it will help change the world, they will often do everything they can to make it work.

Many firms are already investing in the kinds of leading-edge opportunities that will be wildly profitable while addressing the enormous problems that we face. Investors are increasingly turning to environmental, social, and governance metrics—ESG metrics—to help identify firms who are future-proofed in today’s environment. Firms are finding new ways to partner with civil society and local governments to make entire cities and regions fossil fuel free.

Responding effectively to the challenge of climate change requires us to reinvent almost everything—from energy systems, to cities, food systems, transportation systems, supply chains, and how we think about manufacturing. You can spend your time worrying it will be too expensive and can’t be done—or you can join the thousands of business leaders who are already tackling it—because they can see this is a once in a lifetime opportunity to change the world—and make a lot of money in the process.

This article was originally published by Harvard Business School’s Digital Initiative under the title Sustainability is an Innovation Problem.

About the Author

Rebecca M. Henderson is the John and Natty McArthur University Professor at Harvard University, where she has a joint appointment at the Harvard Business School.

[Image: depotpro]