Have you ever received “unhelpful help” at work? Perhaps you have asked colleagues to pitch in on a project—only to find that the effort they put in was subpar, the end result was disappointing, and you had to perform significant rework.

This is an all-too-common problem for businesses, one that can waste employees’ time and companies’ money, says Teresa Amabile, the Edsel Bryant Ford Professor of Business Administration, Emerita, at Harvard Business School. Yet receiving unhelpful help may result not necessarily from a lack of competency on the part of the help-giver but from a lack of clarity by the help-seeker.

Take “Mike,” for example, an employee at Glow, a creative design firm Amabile studied that encourages its entire staff to both offer help and ask for it regularly. When a project team asked Mike for help, he got the impression they didn’t know exactly what they needed. He didn’t have time to work with them on figuring that out, so he gave them some quick suggestions—but his input fell flat, leaving both Mike and the team feeling frustrated and let down.

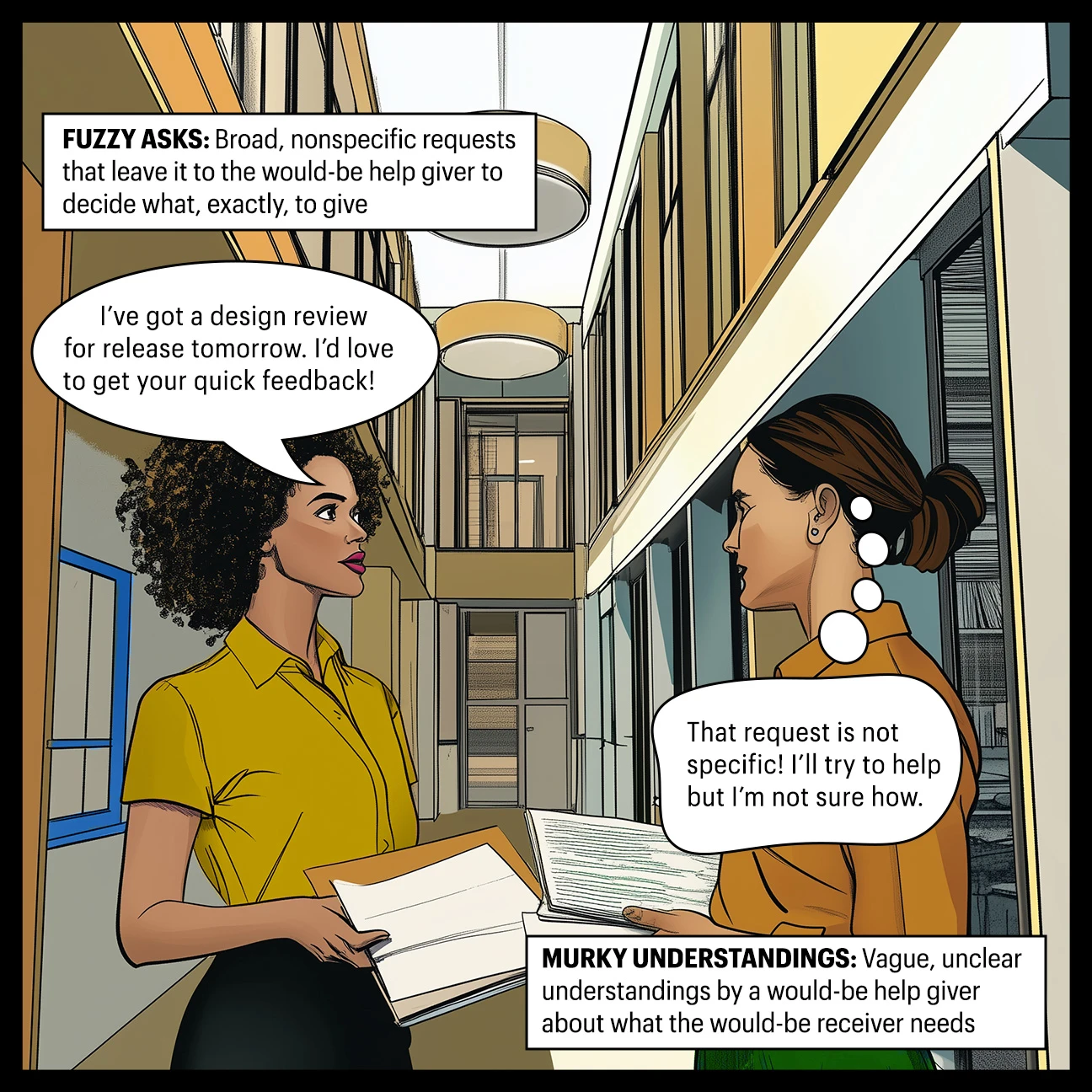

“They made a fuzzy ask, and he had a murky understanding,” Amabile says. What would work better for everyone involved, she says, is for organizations to consider training people on how to ask for and provide the right kind of help.

“Why not have training to help people figure out how to avoid the problems that crop up in asking for help or during the help itself?” says Amabile. “What does effective help look like? And how does it happen? You could train people not to do fuzzy asks or make the other mistakes our research discovered.”

Amabile’s paper, “When the Thought Doesn’t Count: The Dynamics of Unhelpful Help in Creative Organizations,” was recently published in Academy of Management Discoveries. Colin M. Fisher of University College London and Julianna Pillemer of New York University coauthored the research.

In the interview below, which has been lightly edited for clarity and length, Amabile discusses the challenges of cultivating helpful help and explains how employees can ask for and receive more meaningful help.

How would you define unhelpful help?

If someone agrees to help with an issue, problem, or complex task but ends up delivering nothing or something of little or no value, that’s unhelpful help.

How did you come to study unhelpful help?

I have been interested in creativity in organizations for many years, so we decided to do a study specifically focused on helping creative work. We had heard about Glow because it had a reputation for many things, one of which was being a fabulous award-winning design firm. And it had a reputation for being a place where help abounds. One of the first things our research team found at Glow was a culture where employees know that, from the minute you walk in the door, you ask for help when you need it and you give help when you're asked. To not do both of those is to do something wrong at Glow.

They made what we call a 'fuzzy ask,' and he had a 'murky understanding,' and in the end they felt under-supported and he felt underappreciated.

We studied four projects, sending daily diary text messages where we asked people on the project team: Did you get help today? Describe what it was. And rate how helpful it was. Then, at the end of the week, we interviewed each person to get more information on each helping instance they reported by text. Across the four teams, we got data on 230 helping episodes. The majority of those incidents, 75 percent, were rated as quite helpful, but that meant that 25 percent of the time, people who were getting help found it unhelpful. We had previously published a paper on the helpful episodes, but we decided it was just as important to understand how unhelpful help happens as well.

Could you unpack an example of unhelpful help at Glow?

In that one project, the help giver [Mike] was asked to “come in and just be part of the discussion.” The project team was floundering, and nobody clarified for him what they were looking for. And to be fair, they probably didn't know exactly what they needed. They just knew that the project was in trouble.

Mike suspected that they had an even deeper problem: Their relationship with the client was not a collaborative one. But he knew he did not have the bandwidth to sit there with them and get deeply engaged in trying to figure out: OK, what exactly is the problem here? How are we defining what we're trying to design for this client? And let me see if I can talk to the client and with you and try to improve the communication between the two of you. He knew that would have been days of commitment.

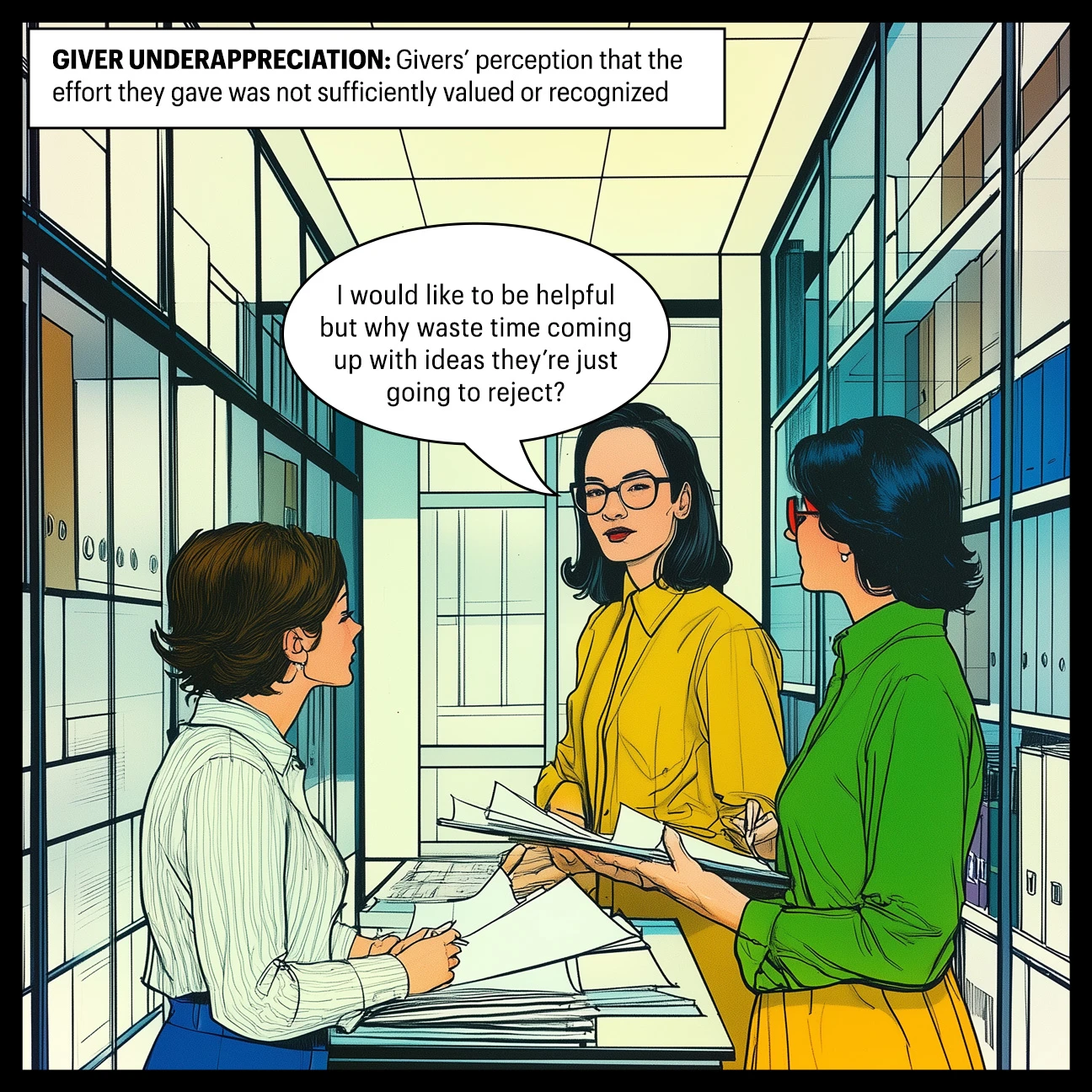

So he came in and gave them some suggestions on a PowerPoint presentation they were going to give to the client, and they thanked him. But he kind of suspected that wasn't what they needed—and it wasn't what they needed. They made what we call a “fuzzy ask,” and he had a “murky understanding,” and in the end they felt under-supported and he felt underappreciated.

What should that project team have done instead?

They could have been more clear, asking Mike something like: “Could you come in and talk with us as we tell you about the project, where it is, the stumbling blocks we've run into, and help us figure out what the real problem is?” That would be a very clear ask about a murky problem. That kind of clarity right up front could have avoided a number of the unhelpful episodes that we saw at Glow.

What is “deep help” and how does it differ from unhelpful help?

The helpful help for creative projects that we discovered at Glow was what we call “deep help,” and there were two varieties:

The first one involves getting in there with a project team and spending significant time with them on a particular problem in sessions that are closely clustered together, generally within just a few days.

The second kind extends over the whole project, and it means helping the team with a variety of smaller tasks, but in a committed way. “I'm your go-to person to help you with this, that, and the other things.”

Unhelpful help can be a one-off thing, such as: “I can come in and help your team create this survey in an afternoon,” but what’s given isn’t what the team needs. Or the giver agrees to help but doesn’t follow through. The help just never really happens.

Another kind of unhelpful help happens on a more substantial issue, and the giver does follow through. So, say the team asks the giver to come in and be part of a major design review with the client. They’ll go in and do it, but do something superficial. It was help, but it wasn’t really getting to the heart of what the team needed.

How can companies cultivate the right kind of helpfulness?

There is research showing that, when help is more abundant, organizations tend to perform better. There are great benefits if you do it right. You'll also have to realize that, if being helpful is part of the role you want people to take on, they will be allocating some of their time to it. Can you give them that time?

Jobs are busier and busier these days, especially for knowledge workers. They’re stretched, so there’s not enough time in any week to add one more thing. If you expect helping to just happen without it being a formally promoted practice of the organization, an expected part of everybody’s role, with time allowed for it—I don't think it would happen.

Think about whether you really want a culture where people are going to be using some of their time to help each other. If the answer is yes, then promote that as an important value. Then train everyone in the organization how to formulate good, clear asks for help when they need it—and when they’re asked for help, how to be sure they understand and can deliver on exactly what’s needed.

Image by Ariana Cohen-Halberstam for HBSWK