As pop stars have sung for decades, money can’t buy love—nor can it purchase fidelity, honor, or even a sincere apology. Instead, humans can only get these most coveted commodities from other people—and they certainly don’t come easy for everyone.

These intangible “sacred goods” are always in short supply and can be tough to manage, but viewing these qualities and experiences through a market lens might reveal ways to develop more of them, argues Harvard Business School Professor Debora Spar.

“We as humans have decided what we can and can’t sell,” says Spar, the Jaime and Josefina Chua Tiampo Professor of Business Administration and senior associate dean for business and global society. “But one of the great benefits of markets is that they produce more of the things we love and want and need. So how can we produce these things if we can’t put them in a market?”

In the recent working paper, Priceless: How to Create, Trade, and Protect What Matters Most, Spar conducts a thought experiment examining how market principles might help people tap into life’s emotional riches. She dubs these collective qualities—the priceless things that make life better—the “sacred economy.”

You want to be treated with respect, you want to feel special, and safe, and feel like you are on an adventure.

While businesses might not be able to put a price on love, respect, children, marriage, or hope, she says, they can benefit from helping their customers achieve those sacred goals. As businesses increasingly turn to artificial intelligence to manage consumer interactions, it will become more important to provide the human-to-human service that customers value.

“When you buy a plane ticket, you aren’t just looking for a way to get from Boston to Amsterdam,” she says. “You want to be treated with respect, you want to feel special, and safe, and feel like you are on an adventure.” When companies focus too much on saving costs, she says, “we’ve lost track of the sacred.”

Getting better at sacred transactions

Spar, author of the book The Baby Business, which examines the fertility industry, says: “I’ve always been fascinated by things that sit at the edge of markets. Everyone on the planet agrees we should never sell babies, but we’re selling the components of babies, and increasingly selling the ability to manipulate at a very foundational genetic level what a baby will be.”

That work led her to examine other elements of life and society that might fit into the same category—things we cannot buy or make for ourselves but must acquire through a human exchange. Marriage, for example, used to be an explicit financial transaction. “Women were ‘given away,’” along with their dowries, Spar says. “Now it’s not a real estate transaction, thank God, but it’s still a transaction—everyone in a relationship knows that.”

Making that transaction succeed goes beyond keeping track of how many times one partner does the dishes while the other walks the dogs, she says, and instead encompasses a more profound exchange of physical and emotional needs. “If one person is doing all the ‘producing,’ if you will, and the other person is doing all the ‘using,’ it’s not going to work.”

If you think about the demand for children, sex, affection, praise, where does that come from? And are there ways ... to bring supply and demand into closer proximity?

The same idea could be applied to the love between children and parents. “Whether they’re small or adult, children have a finely attuned sense of imbalance between siblings of love or time or care,” Spar says. “What the idea of the ‘sacred economy’ does is try to capture these transactions, instead of getting all mushy when we talk about them. If these are the things that we care about the most, then we should be able to get smarter about how to do them better.”

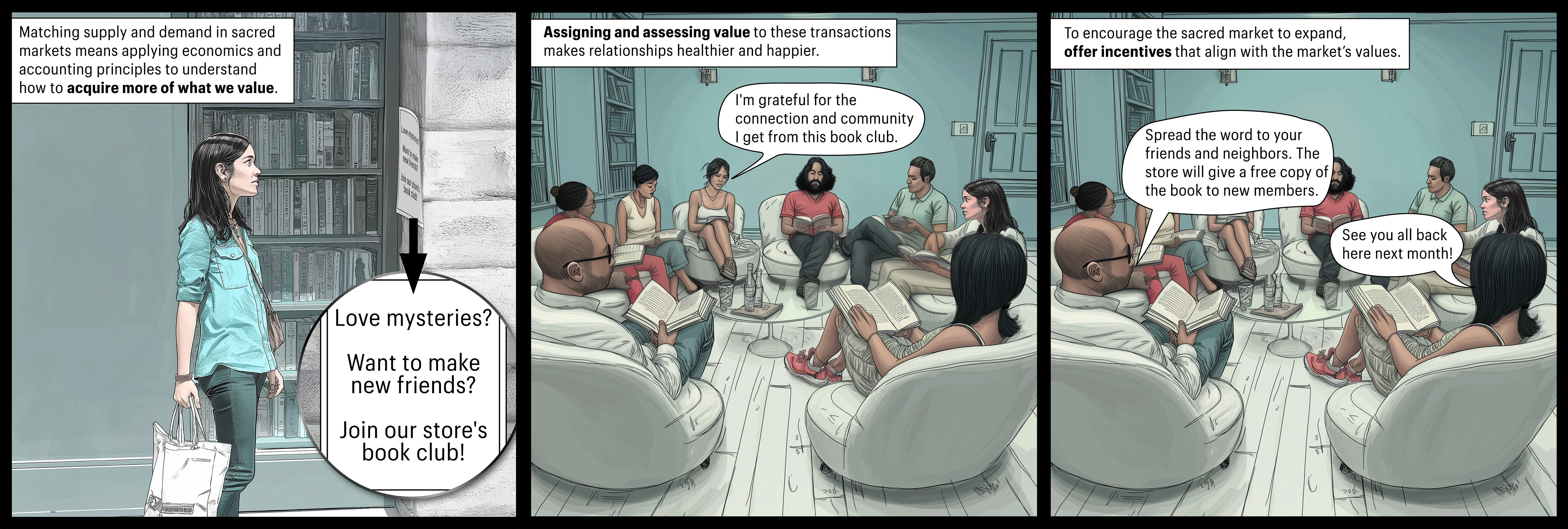

In the paper, Spar says sacred goods can be conceived of as tools in an intangible economy in three main ways: by matching supply with demand; assigning and assessing value; and expanding supply.

Have feedback for us?

Priceless: How to Create, Trade, and Protect What Matters Most

Spar, Debora L. "Priceless: How to Create, Trade, and Protect What Matters Most." Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 25-028, November 2024.