Here’s some bad news and some worse news for women who aspire to the executive suite.

The bad news is that there’s a huge gender gap in top corporate positions, both in terms of the number of female executives and how much money they make compared to men.

Our results point towards the possibility that male and female executives sharing equal attributes neither have the same probability of reaching the top, nor are they paid equally

The worse news is there doesn’t seem to be much women can do to close that gap—no matter how talented, educated, skilled, lucky, ambitious, or genetically gifted they are—unless they can figure out a way to thwart discrimination.

That’s the frustrating takeaway of the new research paper “Equal Opportunity? Gender Gaps in CEO Appointments and Executive Pay,” written by Matti Keloharju, a visiting scholar at Harvard Business School; Samuli Knüpfer, a finance professor at BI Norwegian Business School; and Joacim Tåg, program director at the Research Institute of Industrial Economics.

In their study, comprising an entire nation of executives, the researchers systematically tried to suss out a logical explanation for the gender gap, aside from unmeasurable factors like chauvinism. They mostly failed.

But in failing to find a quantifiable explanation, they succeeded to challenge a commonly held notion that the corporate gender gap can be attributed to observable, measurable, controllable factors such as a woman’s intelligence level, the amount of time she takes off to raise children, or the quality of her network connections.

Career paths are different for men and women in Sweden and elsewhere. ©iStockPhoto/Delpixart

“Our results point towards the possibility that male and female executives sharing equal attributes neither have the same probability of reaching the top, nor are they paid equally,” the researchers write.

An entire nation of data

To investigate the gender gap, the research team collected data on virtually every person who worked as a top executive in a Swedish firm between 2004 and 2010. They chose Sweden because data on citizens and firms is unusually available, compared with other nations. (When I ask Keloharju about the “Swedish data sample,” he gently corrects me. “This data is extraordinary,” Keloharju says. “It’s not a Swedish sample. It’s all of Sweden.”)

The researchers began their study by documenting the gender gap among companies in Sweden. They excluded family-run companies, because in those cases the CEO was likely to be the founder or a descendent of the founder. And they focused only on executives—comparing women at the top with men at the top.

“Given that executives are a more homogeneous sample, whatever unobservable differences that exist [between men and women] are likely to be smaller than a sample of all employees,” Keloharju says. “Because they are executives, both the men and the women tend to earn more than the rest of the population, so they all can afford to hire nannies, for example.”

Looking at data from the Swedish Companies Registration Office and Statistics Sweden, they found that male executives earn 27 percent more than female executives, on average. The pay gap is smaller at the very top of the C-suite; male CEOs earn only 7.1 percent more than female CEOs. But whereas women comprise 21 percent of senior executives in Sweden, they account for only 8 percent of CEOs.

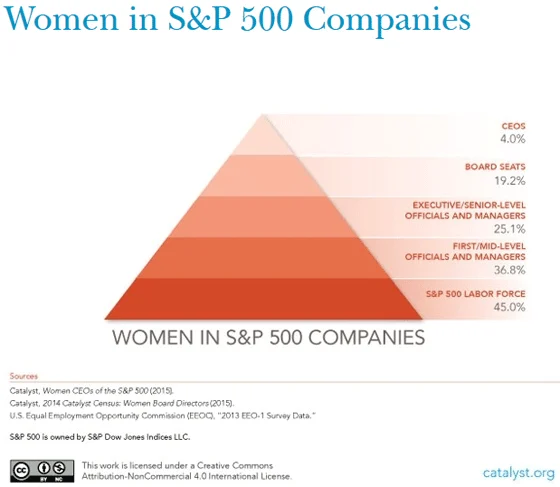

This Catalyst Pyramid visually highlights the gender gap in the labor force, two levels of management, board seats, and CEOs in companies listed on the S&P 500.

While the study focuses on a single nation, Keloharju believes the findings are generalizable to other countries, including the United States. Widely cited for its management practices, Sweden has 24 companies on the Forbes Global 2000 list of largest companies in the world, for instance, and on a per capita basis, there are substantially more Swedish companies on the list than US companies.

The comparability caveat is that Sweden may be more egalitarian than most countries. Globally, Sweden has the fourth-largest female representation in the corporate boards of companies listed on stock indices, at 28.5 percent. (In the United States, women’s share of board seats on the S&P 500 is 19.2 percent.) In other words, inasmuch as the gender gap is intractable in Sweden, it’s probably more so in most other countries.

It is standard practice for researchers to test for multiple variables that might help explain the results. In the Swedish study, Keloharju and team wanted to separate the observable variables (like differences in educational background) from unobservable variables (like inherent discrimination against women). In total, the researchers factored for a whopping 85 observable characteristics in an attempt to elucidate the huge differences in appointments and pay among top executives.

I believe that some type of discrimination would be the most likely story

The categories they studied included level of education (e.g. high school vs. university); educational specialization (e.g. economics vs. social sciences); family background (e.g. birth order and where the executive grew up); career (including years of labor market experience and number of days unemployed); and current family status (e.g. marital status and number of children at home).

Using data from the Swedish Military Archives, the researchers factored for personal traits, including imputed height, body mass, and cognitive ability. Because military service was mandatory for men but not for women, they had very little data on the physical traits of the women. They made up for that lack of data by incorporating data about the executives’ brothers, reasoning, for example, that tall people tend to have tall brothers.

They looked at differences in risk tolerance, measured by whether the executive played the stock market. They looked at network connections, such as whether the CEO and board chair had gone to the same high school. They looked at the employment record of the executives’ spouses, noting, for example, whether the spouses also worked or stayed at home with the kids.

Key differences don't explain the gap

In the end, they did document some key differences between male and female executives. For example, female executives are less likely to be married, more likely to be divorced, and have fewer children than male executives, on average. Of those who are married, female executives are likelier to be married to another executive than are male executives. Female executives are more likely to work for government-owned or privately held companies than men.

Female executives are on average better-educated than male executives, the one variable that noticeably widened the gender gap after controlling for the 85 factors. (To put it another way: The most measurably successful way to bridge the gender gap, getting a good education, is something the majority of these women had already done.) And the women in the sample proved to be more risk-averse than the men, a factor that narrowed the gap.

But despite analyzing a comprehensive set of data, the 85 observable variables explained only 10 percent of the appointment gap between male and female CEOs and 13 percent of the pay gap. “We threw in everything we possibly could to kill the gap,” Keloharju says. “We had an extremely large set of plausible variables. And we were not able to explain basically anything.”

This is all to say that the primary causes of the gender gap seem to be unobservable according to scientific research standards.

“I believe that some type of discrimination would be the most likely story,” Keloharju says. “But, I mean, we can never measure that directly.”