There's an old fable in which a scorpion asks a frog for a piggyback ride across a river. The frog fears getting stung along the way, but the scorpion argues that stinging the frog would be fatally stupid; the frog would die and sink and so, too, would the scorpion. So the frog concedes. Halfway across the river, the scorpion stings the frog. "Sorry about that," says the scorpion, as they both drown. "It's just my nature."

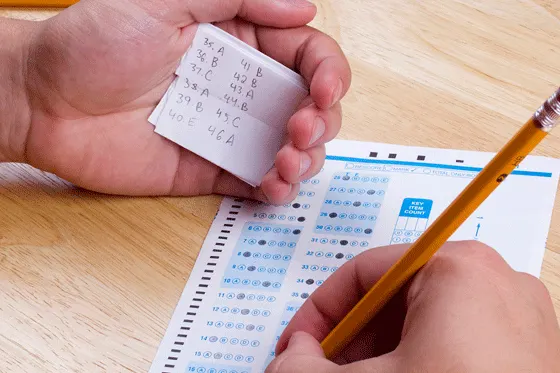

It turns out that people, like the scorpion, may be biologically predisposed to behaving badly. In short, our hormones may foretell whether we'll lie, cheat, or steal.

We wondered if there were biological or physiological factors that could help to explain the misconduct that we see so frequently in the real world

A new study reveals two key discoveries about the link between the endocrine system and unethical behavior. One, certain hormones predict the likelihood of whether someone will behave unethically. Two, among those who do cheat, cheating reduces levels of the hormone associated with psychological stress. In other words, people may use cheating as a means of relieving stress.

The good news is that corporate cultures and organizational structures may play a role in regulating hormone levels in employees. The bad news is that far too many business situations actually fuel the very hormones that trigger unethical behavior.

The findings are detailed in the paper Hormones and Ethics: Understanding the Biological Basis of Unethical Conduct. Published in the August 2015 issue of the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, the paper was co-authored by a team of behavioral economists and psychologists: Jooa Julia Lee, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University; Francesca Gino, a professor in the Negotiation, Organizations & Markets unit at Harvard Business School; Ellie Shuo Jin and Leslie K. Rice, doctoral students at The University of Texas at Austin; and Robert A. Josephs, professor and head of the Clinical Neuroendocrinology Laboratory at UT Austin.

Employers may be able to reduce cheating and other bad behavior

among employees by understanding the role of hormone levels. ©iStock.com/VIPDesignUSA

For eons, academics have studied the forces behind unethical acts, disturbed and intrigued by scary real-world data on corporate corruption. The Association of Certified Fraud Examiners reports that a a typical organization loses 5 percent of its revenues to fraud annually, which translates to a projected global fraud loss of $3.7 trillion.

Most of those studies, however, have focused on the practical logic behind the crimes. What sets this study apart is that it is among the first to delve into the primitive, animalistic processes driving bad behavior. "In the general area of ethics, we seem to have learned a lot over the last few decades about when and why good people do bad things," Francesca Gino says. "But we wondered if there were biological or physiological factors that could help to explain the misconduct that we see so frequently in the real world."

The Lab Experiments

The research team conducted a series of experiments to study the effect of two important hormones: testosterone (associated with decreased fear and increased sensitivity to status and dominance) and cortisol (associated most commonly with acute and chronic stress). Both hormones are found in men and women. Men naturally have more testosterone than women do, but the researchers were measuring the levels relative to gender norms. The normal level of cortisol is the same for both men and women.

For their main experiment, they recruited 120 adult participants, a mix of men and women, and asked each to complete 20 math problems. The researchers then measured participants' hormone levels via saliva samples, both before and after the math exercise.

All participants received $10, with an opportunity to earn an additional dollar for every problem they solved correctly. The participants graded their own papers and reported their own performance, meaning they had both an opportunity and an incentive to cheat.

Unbeknownst to the participants, the researchers were able to measure actual performance against stated performance, so they could tell who had overstated the number of correctly solved problems. Overall, they found that some 44 percent of the participants cheated on the task.

Next, the team compared the hormone levels of the cheaters with those of the non-cheaters. They found the most egregious cheaters were participants who came into the study with especially high levels of both testosterone and cortisol. However, a high testosterone/low cortisol combination did not predict cheating, nor did a low testosterone/high cortisol combination, nor did a low testosterone/low cortisol combination.L

Prior to starting the experiment, the researchers expected that elevated testosterone would encourage cheating. Previous studies have shown that elevated testosterone increases sensitivity to reward while decreasing sensitivity to punishment, which encourages risky but rewarding behaviors such as cheating.

Cortisol, meanwhile, is known colloquially as "the stress hormone," because cortisol levels go up when people experience stress. An analysis of the post-math-test saliva samples, compared with the pre-math-test saliva, revealed something unexpected and disturbing: The more a participant cheated, the greater the participant's decrease in cortisol after the cheating occurred. Relatedly, the more a participant cheated, the greater the participant's decrease in self-reported psychological distress.

"This indicates that cheating may be used as a stress reduction mechanism, and that maybe people will reduce their performance-related stress by engaging in unethical behavior," says Jooa Julia Lee.

Real-world Implications

The researchers acknowledge that additional studies will be needed to determine cause and effect between hormones and unethical behavior in the real world. For one thing, they want to establish whether anxiety about the unethical behavior leads to a vicious cycle of cheating-to-relieve-the-stress-of-getting-caught-cheating. (When providing the first saliva sample for the study, participants were unaware that they were about to embark on a task in which they could cheat.)

Definitive answers aside, the initial findings suggest it is important to pay attention to the role of hormones in bad behavior—and to the possibility that organizations can influence people's hormone levels. "If you're setting up an environment that affects people's hormones in a certain way, you might affect the choices they make when it comes to something as important as cheating," Gino says.

It's worth noting that some of the most deliberately stressful organizations tend to attract the most naturally forceful people. Based on the researchers' findings, the people most likely to cheat are those who are both aggressive (high testosterone) and stressed (high cortisol). Consider Wall Street, where hard-hitting bankers compete for performance-driven bonuses, where "You eat what you kill" is the informal motto, and where investment fraud is a major problem.

"Many organizations base performance not only on incentives that increase stress and anxiety, which will elevate cortisol, but also on incentives that appeal especially to the highly ambitious, which will elevate testosterone," says UT's Robert Josephs. "These organizations are basically creating the perfect storm for the hormonal encouragement and maintenance of unethical behaviors."

It probably doesn't help that many businesses try to thwart potential fraud by threatening employees with severe consequences—increasing stress and thus elevating cortisol. "If you think about how many organizations deal with unethical behavior, it's often by making people feel anxious and stressed out," Gino says. "This is potentially dangerous, because when you add cortisol to testosterone, you're going to end up with more cheating rather than less."

What To Do?

So how should organizations change their ways, considering the findings of the hormones and ethics study?

For profit-based businesses, the researchers suggest a compensation system that includes more than just individual financial results. Past studies on the role of testosterone in competition have shown that it's possible to diminish the influence of testosterone by rewarding group performance over individual performance. "A manager could change the incentive structure to be more focused on growth or other dimensions besides those that are focused just on individual performance," Lee says.

The research also provides incentive for academic institutions to address performance-related stress, especially at schools that attract highly driven, highly competitive students.

"We've known for a long time that chronically elevated levels of physiologic stress and psychological distress lead to the development of a wide variety of diseases, many of which are deadly," Josephs says. "What we didn't know, and what our research suggests, is that stress may also contribute to a social disease—namely, unethical behavior. Thus, the trick is to figure out ways to reduce stress. If we can substitute an alternative to cheating that is a healthier, more prosocial means of reducing stress, then we might rob potential cheaters of the desire to cheat as a means of lowering psychological distress. This strikes me as a very real possibility, and one that could be implemented by a wide range of mental health and lifestyle professionals."

On a personal level, we probably don't do ourselves any favors when we panic about our own goals. Freaked out because you smoked a cigarette after vowing to quit? The resultant cortisol boost may induce you cheat on your vow further, and sneak another one. Losing sleep because you cheated on your diet with a piece of delicious bacon? Getting worked up may just lead you to eat more bacon. (To add insult to injury, medical studies suggest that a high level of cortisol leads to an accumulation of abdominal fat.)

CBS This Morning co-host Gayle King recently interviewed comedy star Melissa McCarthy, and asked for the secret to her recent weight loss. "I finally said, oh, for God's sake, stop worrying about it," McCarthy replied. "And it may be the best thing I've ever done."