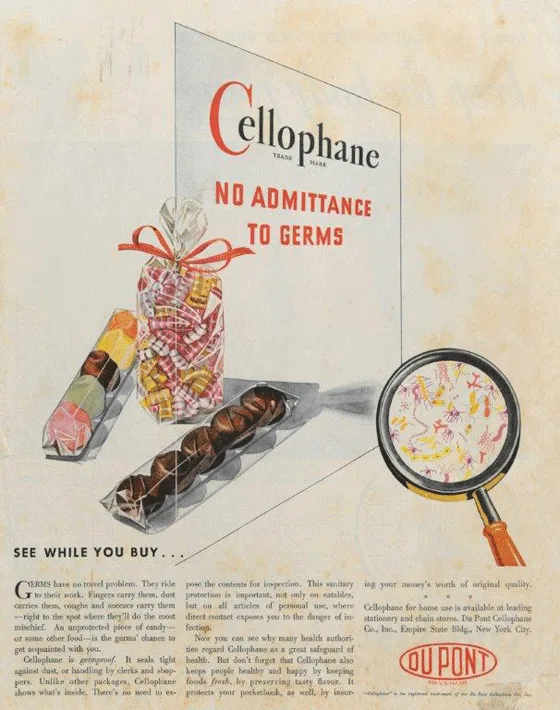

Advertisement for DuPont Cellophane from The Saturday Evening Post, 1950. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Advertising Department records (Accession 1803), Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware

Don’t feel bad if you haven’t spent much time considering cellophane. It’s deliberately transparent, after all. You’re meant to consider whatever it’s wrapping instead.

Yet, it turns out that cellophane has a story worth telling. A new research paper exposes the historical significance of the packaging material, focusing on its key role in the development of self-service merchandising systems in American grocery stores, but also revealing how cellophane manufacturers tried to control the narrative of how women buy food.

“Cellophane changed how people shopped,” says Ai Hisano, the Harvard-Newcomen Fellow in Business History at Harvard Business School and author of the paper Cellophane, the New Visuality, and the Creation of Self-Service Food Retailing.

Cellophane played a big part in how the color of food started to be controlled and standardized

Hisano is at work on a wide-ranging book about the history of creating the color of foods, which has been the focus of her research during her yearlong study at HBS. She’ll present some of her findings at a June 29 workshop called “Capitalism and the Senses,” which “brings together scholars from various disciplines, including marketing, history, and anthropology, to explore how businesses developed marketing strategies to appeal to consumers’ senses from the nineteenth century to today.”

Cellophane gets an entire chapter in Hisano’s book. As she explains in the paper, cellophane packaging let food vendors manipulate the appearance of foods by controlling the amount of moisture and oxygen that touched a product, thus preventing discoloration. “Cellophane played a big part in how the color of food started to be controlled and standardized,” she says.

The rise of self-service grocery stores

Through the turn of the 20th century, especially in cities, Americans tended to shop for food either at large outdoor markets or at local grocery stores.

At the outdoor markets, shoppers fended for themselves, relying on their senses. They eyed, touched, sniffed, and even tasted the goods to guide their purchasing decisions—all the while getting socked in the face with the smells and sights of chicken coops, dead pigs, and other barnyard realities. But at the local grocery stores, food was often kept either behind the counter or in a back room, hidden away from the public, and consumers depended on the grocer or butcher to choose the food for them.

Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, more and more grocery stores converted to self-service retailing, displaying products in the open so that consumers could choose for themselves. The rise of supermarkets spurred the trend, as did the availability of refrigerated shelves, which enabled the safe display of food that would otherwise spoil.

Also vital to the adoption of self-service retailing: the invention of cellophane, and continual improvements to the product. As it turned out, the evolution of self-service retailing in the United States was directly tied to the evolution of transparent packaging. Reasonably, retailers depended on a consumer’s ability to see a product before buying it.

“Especially after the rise of supermarkets, consumers couldn’t talk to store clerks to help them choose,” Hisano says. “But consumers knew how food should look based on their experience.”

A brief history of cellophane

Cellophane, the world’s first transparent packaging film, was invented in 1908 by the Swiss engineer Jacques Brandenberger. He dubbed it “cellophane” as a combination of the words “cellulose” (of which it was made) and “diaphane” (an archaic form of the word “diaphanous,” which is a fancy word for “transparent”). He assigned his patents to La Cellophane Societe Anonyme, a French company formed for the sole purpose of marketing the invention. In 1923, the company licensed to DuPont the exclusive rights to make and sell cellophane in the United States.

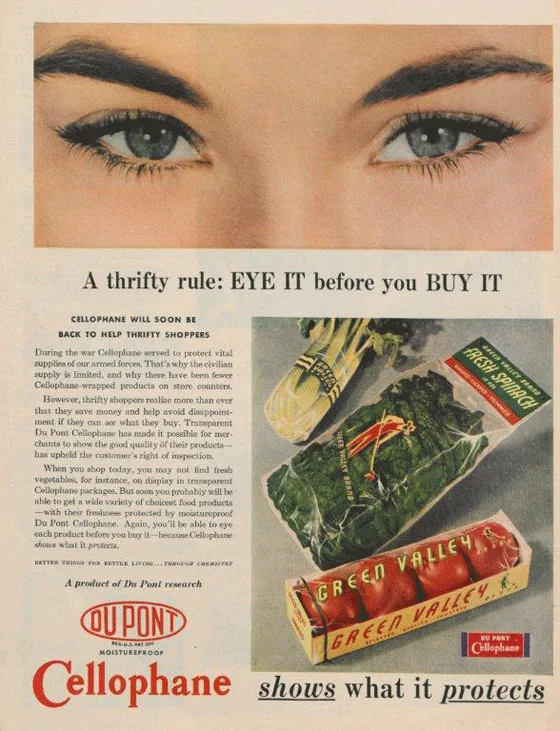

Advertisement for DuPont Cellophane from The Saturday Evening Post, 1933. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Advertising Department records (Accession 1803), Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware

Initial versions of cellophane were waterproof, but not moisture-proof. So, while it was effective for wrapping products like candy and cigarettes, it wasn’t effective for packaging fresh food. In 1927, DuPont developed moisture-proof cellophane, food manufacturers started using it to package items like cakes and cheeses, and cellophane sales tripled between 1928 and 1930.

While other companies developed transparent packaging of their own, DuPont remained the market leader, either by staying ahead of the competition or, in one case, by suing them for patent infringement. (DuPont sued Sylvania in the early 1930s and ended up licensing the company to manufacture cellophane under DuPont patents.)

By 1938, cellophane accounted for 10 percent of DuPont’s sales and 25 percent of its profits. “Between 1925 and 1938, its return on investment averaged 36 percent, over twice that of chemically similar rayon,” says Hisano, citing the book Science and Corporate Strategy: Du Pont R and D, 1902-1980.

DuPont aggressively marketed the idea of better-selling-through-cellophane, releasing several self-funded studies on the efficacy of visual marketing. “DuPont’s research concluded that 85 percent of all food purchase was done by the eye,” Hisano writes.

The company fueled the notion that eyes made up for any other senses deprived by cellophane—i.e., while a store’s customers could no longer touch, smell, or taste a product before buying it, cellophane let you imagine how a product smelled, felt, or tasted. One ad in 1930 made the claim that “your EYES can TASTE Cellophane-wrapped candy.”

At the same time, DuPont marketed heavily toward women. “There was a notion among retailers that women were the primary shoppers,” says Hisano, whose upcoming book about food coloring focuses a great deal on how food companies marketed to women.

“These advertisements commonly featured the eyes of women,” Hisano writes. “The illustration of the eyes as well as the advertising rhetoric in the text helped promote the importance of appearance in selecting foods.”

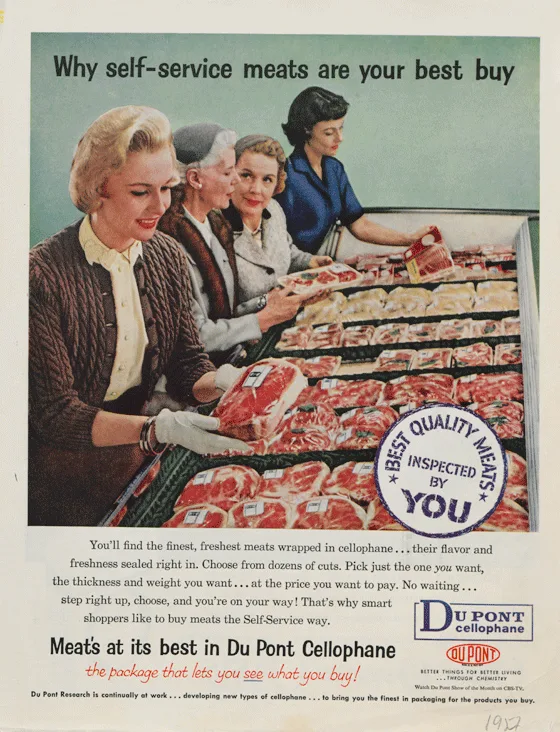

Advertisement for DuPont Cellophane, 1945. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Advertising Department records (Accession 1803), Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware

Yet there was a notable exception to the adoption of self-service retailing: the meat department. Even in supermarkets, the meat-buying process remained akin to that of a traditional local butcher shop, where an expert cut slabs of beef behind the counter on a per-order basis, after conferring with customers individually. Some grocers did experiment with self-service meat marketing in the 1930s, but soon gave up due to refrigeration and packaging challenges.

Not until after World War II did most grocers adopt self-service meat sections. That happened partly due to advances in refrigeration cases, but largely thanks to innovations in cellophane.

What you don’t know about meat coloration chemistry might surprise you

Hisano explains the situation with a brief chemistry lesson in the color of cut beef, which depends on various derivatives of the protein myoglobin. When the meat is first cut, it looks purple. After being exposed to oxygen for half an hour or so, it looks bright red. More time than that, and it begins to develop a brown color. While purple beef is technically the freshest, and while it’s safe to cook beef when it first turns brown, consumers have been conditioned to believe that red equals fresh.

“One of the problems that food retailers faced was the discoloration of meat once packed for self-service,” Hisano explains in her paper. “Meat packers and food retailers described the scarlet red color of meat as ‘bloom,’ which consumers generally considered as a sign of good, fresh meat. But this ‘fresh’ red color did not actually indicate that the meat was the ‘freshest’ in terms of the time it was exposed to the air. Since meats were perishable foods, with colors subject to change, keeping the desired color was a major objective.”

Early versions of "moisture-proof" cellophane still did not possess the amount of moisture control and permeability necessary to keep red meat looking red. But in 1946, following a wartime shortage of cellophane, DuPont finally created a new version of cellophane that struck the perfect balance of moisture control and oxygen penetration. Now meat could turn from purple to red and stay that way for days.

Advertisement for DuPont Cellophane from The Saturday Evening Post, 1949. E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Company Advertising Department records (Accession 1803), Manuscripts and Archives Department, Hagley Museum and Library, Wilmington, Delaware

“By 1953, more than 50 percent of all supermarkets in the United States had offered self-service for packaged fresh meat—a huge increase from 1946 when there were only twenty-eight supermarkets with complete self-service in the meat department,” Hisano writes.

Hisano goes on to describe how some retailers manipulated meat with artificial food additives, in order to maintain—or artificially create—the coveted red color. (She provides an in-depth analysis of artificial food coloring in a previous paper, “Standardized Color in the Food Industry: The Co-Creation of the Food Coloring Business in the United States, 1870-1940,” which describes the paradoxical quest to make food look more “natural” with artificial dyes.)

She wraps up her cellophane paper reminding readers about a common irony in the history of food marketing—that corporations and retailers alike spend a lot of money and effort to create and then meet customer expectations about how food should look.

“Freshness was no longer a natural state of foods but a marker of marketability that producers and retailers carefully controlled,” she writes. “…Cellophane packages were expected to protect the ‘virginity’ of the content and presented it as pure and untouched. But, in fact, keeping the virginity involved tremendous human manipulation.”

Related Reading:

The Paradoxical Quest to Make Food Look 'Natural' With Artificial Dyes

“Blank” Inside: Branding Ingredients