In the spring of 2005, media outlets from Gizmodo to Good Morning America were buzzing about Clocky, an alarm clock that jumped off the nightstand and rolled away chirping and beeping, forcing its owner to get out of bed to turn it off and stop the cacophony.

The publicity was unusual, considering that Clocky wouldn't even hit the market until 2007.

I would kill Clocky in about two days.

—Diane Sawyer

At that point, the device was just a project that Gauri Nanda, a graduate student at MIT's Media Lab, had developed for an industrial design course. She hadn't planned to publicize Clocky beyond a few photos on the course website, but several gadget aficionado blogs found the photos and linked to them. The buzz went viral, eventually garnering Clocky a photo on the front page of the L.A. Times, a mention in Jay Leno's Tonight Show monologue, and a question on Jeopardy!

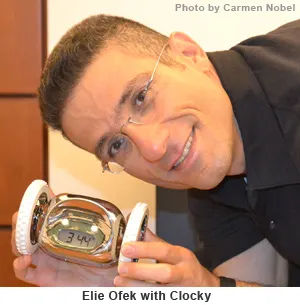

Around the same time, Harvard Business School Professor Elie Ofek was seeking case studies for his second-year Marketing and Innovation course.

"I was looking for new products and innovations that were unexpected successes—things that you wouldn't anticipate to catch on, and yet they did—and trying to see why that happened," says Ofek.

Clocky fit the bill. In the case "Clocky: The Runaway Alarm Clock" (with Eliot Sherman) and the follow-up case, "Nanda Home: Preparing for Life after Clocky" (with Jill Avery, HBS DBA'07), Ofek explores the challenges that Nanda faced in designing, positioning, marketing, and selling the animated snooze-button thwarter, as well as the challenge of expanding the company's product line.

The cases deal with universal entrepreneurial consumer product questions:

Should the product be sold at big-box stores or through upscale specialty boutiques? (Nanda stuck with small museum shops and specialty catalogs at first, in spite of all the advance publicity.)

Is it better to partner with an American product design firm and risk prohibitive expense, or to team up with a less-expensive overseas firm and risk the inherent quality control and communications issues? (Nanda, who was able to launch the product with seed money from family members, retained full design control but subcontracted production to an Asian firm.)

More pointedly, the cases address the reasons for Clocky's startling, unsolicited publicity, along with an issue that faces any entrepreneur looking to build a business around an unconventional product that elicits multiple reactions:

How do you balance fun and function in order to avoid the danger of your product becoming a flash-in-the-pan fad?

Clocky Strikes A Nerve

Until Clocky, there hadn't been any major innovations in the alarm clock market since the 1950s, when General Electric-Telechron started selling clocks with snooze buttons.

"For some reason, we had relegated the alarm clock to be a low-involvement, low-cost item with no emotional involvement, albeit with a very specific function," Ofek says.

But for most of us, our relationship with alarm clocks is both intimate and codependent. It's the last thing we see when we go to sleep, and the first thing we see when we wake up. We rely on it every morning, but we resent the living daylights out of it.

In the "Clocky" case, which Ofek has taught for four years, the authors credit these universal deep-seated feelings for the initial media interest in the product—and for the reactions it engendered among journalists. Following a demonstration of a prototype on Good Morning America, for example, Diane Sawyer said, "I would kill Clocky in about two days."

Fun Vs. Need

When Nanda designed Clocky for her course, she initially had a kitten in mind—a robotic pet that would wake you up in the morning, but that you couldn't help liking because it was so cute. The Clocky on the market today comes in chrome or plastic, but the prototype Nanda built was covered in crude furry carpeting. Yet in marketing the product, she had to be careful to focus on function as well as fun, lest Clocky be relegated to fad status along with past products like Sony's now-discontinued robotic pet dog, the AIBO.

Apple succeeds because in addition to providing an appealing design, it does the functions pretty well.

—Elie Ofek

"Most fad items don't have a functional element," Ofek says. "A Pet Rock doesn't have a functional element. A Tickle Me Elmo toy does not have a functional element. With Clocky, even if the cuteness factor wears off, it still has a functional element. Take Apple products: The design does something to you, but if competitors had products that blew Apple away on function, the design wouldn't win you over. Apple succeeds because in addition to providing an appealing design, it does the functions pretty well."

In the case, Nanda mentions the Roomba, iRobot's robotic vacuum cleaner, as an example of a product that manages to steer clear of passing-fad status.

"I've heard a lot of people say that the first-generation Roomba turned out to be a gadget, a fad item, because after a while it was a hassle to use and provided little results, even if it was always fun to have running around the house," Nanda says. "After seeing its product in the field for some time, iRobot has since improved the original Roomba and is introducing other new products like the Scooba [a robot mop] that are targeted to solve more difficult household chores."

Next Steps

The follow-up case, "Nanda Home," which Ofek began teaching this fall, revisits Nanda and her company, Nanda Home, a few years into Clocky's tenure, when sales had begun to flatten. Revenues in 2009 were $990,000, down from $1.5 million in 2008 and $2.2 million in 2007. Nanda, who had cut the original price of the clock from $50 to $39 in order to spur sales, knew she needed to extend the existing product line or venture into new product categories in order to grow the company successfully.

"This is another lesson for entrepreneurial students," Ofek says. "How do you manage this growth phase?"

The case describes the prototypes that Nanda developed as potential complements to Clocky: Ticky, which sported digital minute and hour hands as opposed to a standard digital interface; and Tocky, which had the ability to upload MP3s so that owners could wake up to their favorite songs rather than beeps.

At the same time, Nanda was playing with new product ideas: a power-saving electrical plug called the Spitlet, which would eject itself from an outlet once its device was fully charged; an ambulatory houseplant pot that would move itself around in order to get adequate sunlight; and the Follo, a roving robot that would act as its owner's personal assistant.

Conducting consumer research on a completely new product idea is a dilemma for many entrepreneurs. "When you come to consumers with a concept that's completely different from what they have or have seen, they'll give you a negative reaction just because it's unfamiliar to them," Ofek says.

History shows us that Nanda took a cue from iRobot and decided to market Tocky.

Ofek remains in touch with Nanda, reporting that she is now mulling the idea of a children's alarm clock to be called Clockiddie or Clockiddo that will not only wake kids in the morning but also tell them bedtime stories and sing songs at night.

"She realizes that for kids it's not just a struggle to wake up, it's also a struggle to go to sleep," he says. "But will the parents buy it?"

Might this be the subject of a third case? "Time will tell," Ofek quips.

In the meantime, Ofek invites Nanda to attend his class when the Clocky cases are taught.

"I think she likes it because it gives her a chance to have people poke at her ideas and propose new ones," he says.