Companies looking to create a culture that celebrates creativity might take a page from the ultimate Silicon Valley playbook: ’s 2009 “culture deck” championing freedom with responsibility.

To woo the best and brightest, the streaming giant rejected top-down decision-making and annual performance reviews, offered unlimited vacation and loose expense policies, and demanded high-performance standards with frequent, frank feedback. Sheryl Sandberg called the deck one of the most important documents ever to come out of the Valley.

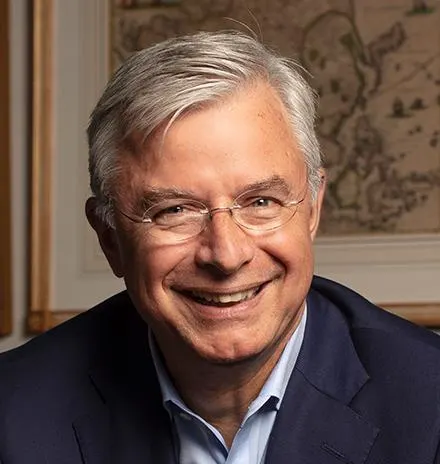

“Culture can be seen as fuzzy and difficult to define,” explains Hubert Joly, a Senior Lecturer at Harvard Business School and former CEO of , who co-authored the case study “Netflix’s Culture: Binge or Cringe?” “If your culture is defined by vague values like customer centricity or integrity, it’s hard to execute. Netflix created a culture around a singular, powerful idea—freedom with responsibility—that set clear expectations designed to support top-performing employees and the belief that great talent improves results exponentially.”

But when the streaming company’s growth slowed, Netflix faced questions about whether its culture was in part to blame. “There are many examples of Netflix succeeding through its culture, but what do they do when things stop working?” asks Joly, who worked on the case with HBS Baker Foundation Professor Leonard Schlesinger. “Netflix must test whether the original idea of the culture is still valid or whether they need to tweak it, given the fact that the context has changed.”

Netflix must test whether the original idea of the culture is still valid or whether they need to tweak it, given the fact that the context has changed.

The tale offers lessons on how to create, adapt, and sustain that squishiest of fundamentals—culture—at a time when instability in both the markets and the political environment tests companies, employees, and customers. Netflix’s unorthodox example also shines a light on how the management basics of a company—from vacation policies to performance reviews—help or hurt innovation.

Wanted: Achievement and autonomy

To many, Netflix is as synonymous with streaming entertainment as Kleenex is to tissues. Founded in 1998, Netflix grew from a mail-order DVD sale and rental service with 300,000 subscribers in 2000 to a streaming service and original content producer with over 300 million global subscribers and $39 billion in revenue in 2024.

Many observers credit Netflix’s success to its unique workplace culture, which is based on the strong point of view developed by co-founder and former CEO Reed Hastings, that highly-talented people don’t like policies, they want freedom.

Hastings elaborated in his book No Rules Rules: Netflix and the Culture of Reinvention: “If you give employees more freedom instead of developing processes to prevent them from exercising their own judgment, they will make better decisions and it’s easier to hold them accountable.”

He added: “If your people choose to abuse the freedom you give them, you need to fire them and fire them loudly.”

Four key ingredients

The 124-page culture deck emphasized:

Talent density. Netflix favored smaller teams of highly talented individuals, especially in creative and technical roles, and terminated average performing staff, using the refrain: “adequate performance gets you a generous severance.” Employees were let go if they could not pass “the Keeper Test”—that is, whether a manager would try to change an employee’s mind if the employee quit. The idea: Fill each role with a star.

Regular, honest feedback. Early on, Netflix did away with performance reviews, finding them too ritualistic and bureaucratically burdensome. Instead, the company expected staff to give routine, candid feedback to other employees, regardless of rank. Withholding disagreement or constructive input was on par with being disloyal to Netflix. Employees were also encouraged to highlight their own mistakes, known as “sunshining.”

Non-hierarchical decision-making. To speed decisions and encourage creativity, Netflix used an “informed captain” model for decision-making. A staff member owned a key decision, aiming to achieve Netflix’s goals rather than “please their boss.” Managers remain involved to share context and advice, not to dictate or control the outcome.

No formal vacation or travel and expense policies. Employees had unlimited vacation, which Hastings explained helped to simplify procedures and reduce costs. “Most important, the freedom signals to employees that we trust them to do the right thing, which in turn encourages them to behave responsibly,” Hastings wrote said in No Rules Rules. Expenses and travel were managed by a five-word guideline: “Act in Netflix’s best interest.”

The downsides of “no rules rules”

Netflix’s culture could be polarizing.

For example, some employees appreciated being surrounded by a dream team of uber-talented employees, while others were paranoid about being terminated and existed in a state of fear. “Sunshining” could cause an employee to lose their job if it revealed significant mistakes.

International employees had varying levels of comfort with Netflix’s practices. For instance, Japanese culture is traditionally non-confrontational, making the frank and frequent feedback challenging, the case says. But in the Netherlands, the more direct, the better. And in some European countries, local labor laws conflicted with Netflix’s approach. Netflix allowed for some adaptations to its culture depending on the country.

Tough times, and doubling down

Netflix soared higher during the COVID-19 pandemic, driven by grateful customers locked inside and hungry for entertainment. But despite Netflix’s meteoric rise, the company hit a rough patch in May 2022. Competition in the streaming space had intensified and Netflix faced slowing revenue, a decrease in its share price, and its first loss of customers in a decade.

The challenging period left some observers wondering if the same culture that propelled Netflix to its highest heights now held it back. Joly asks: “In Netflix’s case, what do you change? Do you revisit Netflix’s purpose to “entertain the world”? Or do you go for the strategy: is it time for another reinvention like when Netflix shifted its value proposition to original content? Or do you tweak the culture?”

Netflix did rebound mightily. By the third quarter of 2023, Netflix began to turn the corner, outperforming Wall Street predictions by adding 8.8 million subscribers that quarter, the largest quarterly increase since the early days of COVID-19. Revenue also increased 8 percent year-over-year that quarter. After the share price had dropped down from a high of close to $ 700 in the fall of 2021 down to below $ 200 in the spring of 2022, it reached close to $ 1,200 in the summer of 2025.

How did they do it? Primarily by tweaking their strategy and value proposition, e.g., introducing an ad-based subscription model, cracking down on password sharing, getting into videogames, live sports, launching a Broadway and opening experiential “Netflix Houses”.

In contrast, they chose not to change their chosen culture, making only minor tweaks to the language. “From a culture standpoint, they didn’t change it; they reinvigorated it,” says Joly, “vindicating a culture that lets top performers, well, perform.”

Epilogue: Levers for managers

Joly suggests three tools for companies to help shape their culture and the need to correct course on culture:

Business levers

These include changes leaders make that directly impact the business, like shifting strategy or tweaking operations, that also directly speak to culture. In the case of Netflix, Joly says the culture had gotten complacent; shifting strategy to go after big new markets like live sports and gaming allowed the company to lean into its original culture again.

Management levers

Joly points to important signals companies send about their cultural priorities based on who they include and who they exclude, and who they reward and why. Companies need to align the nuts-and-bolts of human resources with the culture’s goals.

“Who you put in positions of power, who you invite to meetings, incentives—all these things impact culture,” Joly says. He says that things like what managers emphasize in their business meetings—e.g., starting with people, moving to the business, and leaving financials for last—reinforces a culture that prioritizes talent and customers.

Leadership behaviors

Cultures are sometimes described as hard to change. Joly does not believe it is true and adds: “The way you change behaviors (culture) is by changing behavior. Companies must ask: “Are your leaders culture carriers?” Joly says. “Do they model the behaviors you are trying to espouse?”

Joly also believes in the role of intrinsic drivers of human behaviors such as autonomy, meaning, human connections, psychological safety, learning and a growth mindset, in enabling extraordinary levels of performance.

He believes that leaders can and should shape their behaviors in ways that make these ingredients come to life so that they can “unleash human magic”.

James Barnett and Stacy Straaberg are case writers at HBS and coauthors of the case “Netflix’s Culture: Binge or Cringe.”

Image: Ariana Cohen-Halberstam with assets from AdobeStock.

Have feedback for us?

Netflix's Culture: Binge or Cringe?

Joly, Hubert, Leonard A. Schlesinger, James Barnett, and Stacy Straaberg. "Netflix's Culture: Binge or Cringe?" Harvard Business School Case 522-096, June 2022. (Revised March 2024.)