“Early to bed and early to rise makes a man healthy, wealthy, and wise.”

“There are no gains without pains.”

“One today is worth two tomorrows.”

Some phrases are so familiar they seem to have always existed. Referenced in every imaginable context, they are part of the air we breathe. These pearls of wisdom and many others were made famous by Benjamin Franklin in his 1758 essay known as The Way to Wealth, first published as a sermon delivered by “Father Abraham” in Poor Richard’s Almanack.

I’m interested in how ideas reflect but also change economic realities—and how ideas can translate into policies

Intrigued by the lasting power of Franklin’s treatise on industry and frugality and its influence on capitalism as we know it today, Harvard Business School Assistant Professor Sophus Reinert delves into the history of the essay’s dissemination and impact over the years in “The Way to Wealth around the World: Benjamin Franklin and the Globalization of American Capitalism,” published in American Historical Review (February 2015).

“I’m interested in how ideas reflect but also change economic realities—and how ideas can translate into policies,” says Reinert, noting that the 2008 economic crisis provoked fresh consideration of the relationship between business and society.

“People aren’t occupying Wall Street any longer, but reflecting on where our ideas of capitalism come from and how they’ve evolved over time is one way of offering some new perspective on contemporary debates about the nature of our economic system,” he says. “It helps us understand our moment in time, which seems quite critical.”

Franklin’s reputation as a living legend no doubt helped facilitate the relatively quick spread of his writings, Reinert says. In addition, The Way to Wealth is a quick, somewhat repetitive read that made it accessible to a broad audience—just the opposite of Adam Smith’s voluminous The Wealth of Nations, which was published in expensive folios and directed at scholars and elites.

Influence broader than thought

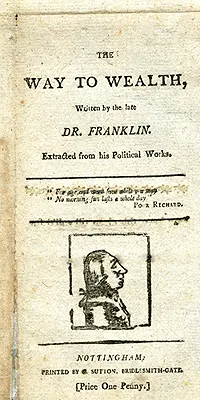

The Way To Wealth.'' (Nottingham: Printed by C. Sutton, Bridlesmith-Gate, [ca.1800?]) Kress Library of Business and Economics, Baker Library Historical Collections, Harvard Business School.

Until now, it was believed that an estimated 145 editions in seven languages had been published before the end of the eighteenth century, but, thanks to the bibliographical research of retired Harvard librarian Kenneth E. Carpenter, we now know there were over 1,100 appearances of Franklin’s The Way to Wealth in at least 26 languages before 1850, making it one of the most widely disseminated economic works in history. Its messages of industry and frugality also found an audience through phonetic spelling and cartoons that appeared on anything from a child’s mug to a popular broadside.

Examples of these early editions can be found in Harvard Business School’s Baker Library Historical Collections. Reinert, in conjunction with Carpenter and HBS Knowledge and Library Services, even developed a Way to Wealth website to provide students and scholars with an online, one-stop-shop that includes a database of editions of The Way to Wealth as well as essays and timeline-maps that show the work’s publication history and geographic influence. Recently, the Center for Research Libraries recognized the site with its 2015 Award for Primary Research.

Although The Way to Wealth appeared in a few South American editions, and made its way to Asia by the twentieth century, resonating with everyone from Mao Tse Tung to Bangladeshi bloggers, Reinert says the essay’s initial influence was limited primarily to North America and Europe, tracking closely with the first parts of the world to enter the Industrial Revolution.

“Most of my research focuses on the history of economic policy and how states have implemented different ideas and pursued different strategies in order to gain a competitive edge,” says Reinert. “Franklin could write for the elites—he did so often. But he chose this specific set of guidelines for virtuous economic behavior to influence the lower people, as he called them. Many readers picked up on this and used the text for their own purposes. While we know from individual workers’ autobiographies that Franklin inspired many to lead more economic lives, statesmen could embrace the text because more industrious workers essentially had become another weapon in international competition.”

While Reinert emphasizes that Franklin’s text is obviously not the sole cause for global economic disparity, he remains intrigued by the role played by institutions and ideals of economic behavior in developing economies.

“The fact that people encountered capitalism as an economic system at a different rate than they encountered the ideals of capitalism—and the long-term consequences of that gap—is worth exploring,” he says, adding that we take for granted many of the virtues Franklin holds up, such as a strong work ethic: “How did hard work and industry become the commonsense default rather than sleeping late and eating berries? How did it become normal to work more than what is necessary for survival? This was one of the texts that helped canonize and codify the basic ingredients of capitalism.”

The Way to Wealth had its critics, too—for some, its popular sayings were a little too virtuous and exacting. “The soul of a man is a vast forest, and all Benjamin intended was a neat back garden,” wrote D. H. Lawrence, with Mark Twain chiming in that it was “calculated to inflict suffering upon the rising generation of all subsequent ages.”

Franklin’s mixed feelings about his message

What gets lost is the author’s own mixed feelings about single-minded pursuit of profit and his hopes for a humanitarian society in which wealth and power are in balance. “Happiness is more generally and equally diffus’d among Savages than in our civiliz’d Societies,” he wrote in 1770. “…the Care and Labour of providing for artificial and fashionable Wants, the Sight of so many Rich wallowing in superfluous Plenty, whereby so many are kept poor distress’d by Want. The Insolence of Office, the Snares and Plagues of Law, the Restraints of Custom, all contribute to disgust them with what we call civil Society.”

Our own time, extreme in its own way, can reduce Franklin’s maxims even further, Reinert says. The shorthand “no pain, no gain,” for example, jumps to rapper Curtis “50 Cent” Jackson’s “Get Rich or Die Tryin’.” Ayn Rand’s John Galt of Atlas Shrugged represents a focalized if selective interpretation of Franklin’s Poor Richard, and continues to stand tall as a heroic, uncompromising paragon of capitalism even as we debate issues of wealth disparity, CEO compensation, tax reform, and raising the minimum wage.

“The role of wealth and wealth creation in society are perennial questions,” says Reinert. “It’s not surprising that we’re discussing them; it’s surprising that we ever stopped at all. Self-reflection and returning to the foundational texts is a healthy part of the evolution of any economic system. How we got where we are seems crucial to the question of where we should go, and what, if anything, needs to be changed.”