Job seekers who want to be paid commensurate with their talent level might want to pursue a career in high finance.

Recent research finds that the finance industry compensates employees largely according to how talented they are. Other high-paying industries? Not so much.

The findings are detailed in the paper Are Bankers Worth Their Pay? Evidence from a Talent Measure by Boris Vallée, an assistant professor at Harvard Business School, and Claire Célérier, an assistant professor at the University of Zurich.

What we are saying is that yes, they are worth their pay, at least in economic terms

The research, based in France, was prompted by an ongoing regulatory debate within the European Union. "In Europe, there has been intense discussion about taxing high incomes in general, and bankers in specific," Vallée explains.

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, the EU passed a rule banning bankers from receiving annual bonuses exceeding more than twice their fixed pay. Lawyers for the United Kingdom actively oppose the rule, which is set to go into effect in 2015. In the meantime, several major banks have responded by increasing executives' weekly cash allowances, in lieu of a bonus. Now the European Banking Authority is looking into whether those allowances are allowable.

"It's a very well-known fact that bankers are paid better than other workers," Vallée says. "We wanted to explain the reasons for the finance premium."

There has been little research on the direct link between measurable talent and its impact on wages. In part, Vallée and Célérier wanted to study talent to challenge the idea that bankers are paid according to how hard they work.

"That's silly," says Vallée, who worked in investment banking at Deutsche Bank in London before pursuing his doctoral studies at HEC Paris. "I've been a banker. I know they work hard. But if a banker works 20 percent harder than someone in another occupation, it doesn't explain getting paid ten times more."

The dearth of research on the wage/talent link was connected to the fact that talent is difficult to measure, Vallée explains. To that end, he and Célérier set out to quantify talent. To do so, they capitalized on data from French engineering schools.

Measuring Talent

In France, students are selected for engineering programs based solely on their national ranking in a standard competitive exam covering a wide variety of subjects. The exam includes more than 80 hours of written testing as well as a series of oral tests. Most students spend two years preparing in dedicated exam-training institutions that are highly selective. Some whiz kids take the exams after only a year of training, while others need to study for three or more years.

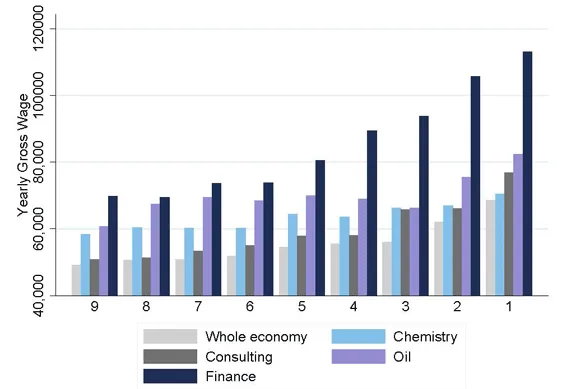

Vallée and Célérier developed a dataset that divided France's 240 engineering schools into nine sections, ranked by selectivity. Group 1 included the most selective schools such as École Polytechnique, which accepts only the top 3 percent of applicants. Group 9 included the least selective schools.

Students accepted into top programs generally have the choice of going to any school they like, but usually choose the most selective school that accepts them. (Education is free in France, so expense is not a factor.)

Thus, the researchers gauged the students' relative talent based on which school they had attended. They also looked at age at graduation, reasoning that a student who was accepted at a top school after only a year of exam training was probably more talented than a student who needed three years of training.

Next, Vallée and Célérier studied the results of a salary survey conducted by the French Engineering and Scientist Council, a network of alumni organizations that includes 144 of the country's 240 engineering schools. Respondents shared their latest yearly salary, current industry, position, and employer. The researchers looked at 324,761 survey responses from 1983 to 2011.

In France, students who complete graduate engineering programs often pursue careers in lucrative fields including chemistry, oil, consulting, and, yes, finance. Thus, the researchers were able to compare how various industries connected wages to talent.

Scalability Matters

The data showed that the finance industry rewarded talented workers to a far greater extent than did other industries. Bankers who had gone to top engineering schools made vastly more money than those who had gone to less selective schools. This gap was much larger than in other sectors such as the oil or chemistry industry.

In 2011, even in the wake of the financial crisis, "returns to talent" were three times higher in the finance industry than in the economy as a whole. (This held true even in cases where the French engineers pursued careers in other countries, including the United States and United Kingdom.) "Having graduated from a school one notch higher in terms of selectivity induces a 2.5% average wage premium, versus a 9% relative premium in the finance industry," the researchers write.

For example, average wages for "low-talent" workers were similar in finance to "low-talent" wages in the oil industry. Among the most talented workers, finance industry wages were 40 percent higher than oil industry wages.

"Oil still pays very well," Vallée says, "but the wage sensitivity to your talent is much lower."

The data showed that the finance industry rewarded talented workers to a far greater extent than did other industries.

So getting back to the title of the paper: Are bankers worth their pay?

"The title of the paper is deliberately provocative," says Vallée. "And the findings are provocative, too. Because what we are saying is that yes, they are worth their pay, at least in economic terms. Because their talent is highly scalable in finance, they are paid accordingly to the profits their talent generates."

According to salary survey results, the majority (65 percent) of engineers in the finance industry are compensated with variable pay, meaning their income varies according to how well they perform. In finance, performance is measured in money. Make more money, get more money.

The findings indicate that if Europe wants its most talented bankers to stay and make money, it may be economically unwise to regulate their salaries.

"If you put a cap on compensation of talented people, then you stop this mechanism, and you run the risk of having your company be less profitable," Vallée says. "You're putting a friction on a competitive market that's doing what it's meant to do."

He notes, though, that market forces may excessively inflate returns to talent in the finance industry. "When rewarding talent, banks tend to focus only on the short-run productivity of bankers, often overlooking long-run risk-taking," Vallée says. "Banks may also neglect tasks that are hard to monitor, such as risk management. Overall, this may harm the stability of the financial sector."

Implications For The Talent Pool

It's not so easy for other industries to offer such competitive compensation packages for talented workers. "Scalability differs a lot across sectors," Vallée explains. "In finance, it's very easy to give you more capital if you make more money. Whereas if you're, let's say, an oil refinery manager, you're not going to get a second refinery next month just because you've done well this month. And even if you're the best wall builder in the world, you're not going to build a thousand walls in a day. It's just much easier to leverage talent in finance."

The research might raise concerns that talent is not spread adequately across industries. The wage premium for talented financiers has increased dramatically and continuously since the 1980s—and increasingly has outpaced the wage premium in other industries. The data show that the percentage of trained engineers holding jobs in finance has grown from 1.8 percent in the 1980s to 2.3 percent in the 2000s. Meanwhile, the percentage of engineers in the oil industry has shrunk from 3.1 percent in the 1980s to .5 percent in the 2000s, and in the chemistry industry from 3.5 percent to 1.8 percent in the 1980s and in the 2000s, respectively.

"We're observing what the market does," Vallée says. "And what the market seems to do is take the most talented engineers and allocate them to finance."