Triumphant Democracy: US Railroads

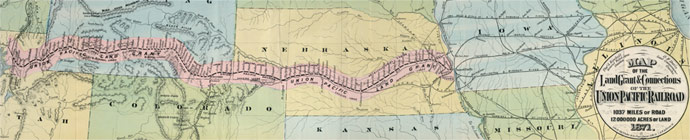

Comparisons with railroad systems abroad underscore the particular circumstances under which the industry developed in America. In Europe, the rails connected existing towns and urban centers. In the United States, the industry helped to open the West, develop the country economically, and create a sense of national unity, while also displacing Native American peoples. Trains carried the US mail and provided the same rights of way for the telegraph lines, setting the foundation for mass communication systems vital to the operations of big business. Rails also took on military significance during the Civil War, when they became strategic in transporting troops and supplies for both the Union and Confederacy.

Bustling new cities like Omaha and Albuquerque sprung up along the lines. As the Morning Oregonian noted in 1883, “Railroad construction . . . has brought great areas of new land within reach of the market, and has supplied the money which has put them under cultivation; it has given to isolated towns the advantage of transportation, and carried new people and money into them; to a thousand old enterprises it has given new life and development, and a thousand new ones have come with it.”17

Opportunities in the industry were not restricted to wealthy merchants or an aristocratic class, but were open to individuals from diverse backgrounds. In his popular work Triumphant Democracy, steel magnate Andrew Carnegie offered his view of the United States as a country of “a strong yet free government . . . where education is every man’s birthright, where higher rewards are offered to labor and enterprise than elsewhere, and where the equality of political rights is secured.”18 He hailed the railroads as a symbol of American democracy and free enterprise, which he believed provided individuals with far greater opportunities than the constraints and traditions of church, state, and class allowed in Europe.

American railroads and the government were continuously intertwined. As was the case in England, railroad companies needed legislative authorization to force landowners to sell their properties for railroad expansion. Significant state and local funding supported the industry initially, and after the Civil War, private enterprise gained more control over the lines. The railroads’ “organizational power was the promise they presented of development, of getting to a coal deposit, timberland, cotton field, granary, or river trading post,” Charles Perrow contends. “States and towns clamored for their tracks. But, being private, for-profit enterprises, the railroads lay down steep terms.”19 Railroad entrepreneurs lobbied for influence over local and state legislators and judges in matters regarding land grants, routes, rates, and reduced regulation, and sought assistance in the form of subsidies and bailouts.