Art, Nature, and Business

Perspectives on the Environment

Organized in conjunction with the Business & Environment Initiative at Harvard Business School, Art, Nature, and Business: Perspectives on the Environment presents works of art from the HBS Art and Artifacts Collections and the Schwartz Art Collection that address a range of environmental topics. This exhibition looks at how various artists have engaged with dialogues on nature, industry, science, ecology, and the environment, from the nineteenth century to the present. The eighteen works in this exhibition explore themes such as the Romantic landscape tradition and the sublime; the artist's experience of nature; constructed environments and ecological systems; innovation, industrialization, recycling, and natural resources; changing weather patterns; the resilience of nature; and the human impact on the planet. Installed throughout the first floor of Spangler Center, this exhibition features art in a variety of media—from paintings and photographs to works that incorporate recycled and industrial materials—in order to bring new perspectives to conversations on campus about climate change.

Exhibition curated by Melissa Renn, Collections Manager, HBS Art and Artifacts Collection.

STEPHEN MALLON

The Reefing of USS Radford, 2012

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.15

This photograph, from Stephen Mallon's solo exhibition The Reefing of USS Radford, is part of the artist's American Reclamation series, which chronicles and examines the American recycling industry, in this case a Spruance-class destroyer in the United States Navy re-purposed to create an artificial reef. The USS Arthur W. Radford (DD-968) was named for Admiral Arthur W. Radford USN (1896–1973). It was decommissioned on March 18, 2003, after 26 years in service, and on August 10, 2011, became part of the DelJersey Land Reef through the Delaware Reef Program, which aims to help depleted or endangered fisheries. Mallon explains: "My American Reclamation series chronicles the beauty of industrial recycling in the United States. In 2010, the USS Radford, a former Naval Spruance destroyer became the longest vessel to be reefed in the Atlantic Ocean. Its final mission serves to create a habitat for marine life and a discovery site for divers."

HENRY P. HUNT

Cutting Ice at Spy Pond, Arlington, Massachusetts, 1859

Oil on canvas

Gift of Frederic Tudor to the Business Historical Society, 1934

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1934.2

This painting by Henry P. Hunt depicts the Tudor Ice Company harvesting ice from Spy Pond in the town of Arlington, Massachusetts. Established by Frederic Tudor in Boston in 1806, prior to the age of refrigeration, the Tudor Ice Company transported ice by rail and ship from freshwater ponds to locations around the world, including India, Singapore, Jamaica, and Cuba. In the case, "The Ice King," Professor Tom Nicholas illustrates how Tudor pioneered a new industry, creating a global market for a natural resource once considered worthless, and became a key figure in the history of American entrepreneurship. Hunt's painting is an important document of Tudor's innovative industry, and can also be a model for 21st-century entrepreneurs investing in new technologies and experimenting with novel ways to use natural resources. The Tudor Company Records are held in Baker Library Special Collections.

DAN FORD

Melville and Hawthorne (American Poetry), 2000

Oil on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.18

Contemporary artist Dan Ford's painting is a witty play on Asher B. Durand's 1849 Kindred Spirits (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), which portrays the artist Thomas Cole and the poet and critic William Cullen Bryant in the Catskill Mountains. Here Ford reworks Durand’s iconic painting, substituting Cole and Bryant with the writers Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne in the foreground, and inserting a McDonald’s restaurant in the background as his comment on the changing American landscape and the "blizzards of convenience" that have "blanketed New England in malls and McDonald's" in his lifetime. Unlike Durand’s painting, where Cole and Bryant contemplate the kindred arts of painting and poetry while walking in nature, here, as Ford describes, "Melville and Hawthorne...go for a wander through the primordial forest and come upon the sublime vision: the Golden Archway!"

JAMES CASEBERE

Flooded Hallway, 1998–1999

Dye destruction print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2003.5

© 2020 James Casebere

James Casebere's photograph shows a hallway flooded with water. However, this is not a photograph of an actual flooded building, but rather of a table-top model the artist constructed that uses a special type of poured resin known as "E-2 Water" to create a simulation of a flooded space, which both challenges the idea of the photograph as a document and pushes the boundaries of the medium. Casebere began making these images in 1998. In an interview with fellow artist Roberto Juarez, he stated: "The first image where I did use water was...based on photographs of flooded bunkers under the Reichstag. The water as a metaphor is about the passage of time. It's about temporality. But it’s also about emotion, an excess of emotion...about some sense of fullness. Maybe it’s a fear of drowning. It's also a sense of overflow—good or bad—but movement." As Juarez noted in response, "Casebere's photographs evoke our deepest fears and longings' and also “captivate our collective imagination, the one ruled by instinct." Viewed in the context of climate change, rising seas, and extreme floods happening today around the world, Casebere's conceptual constructions can also take on new meaning.

MILER LAGOS

195 Rings, 2010

Newspaper collage

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2011.12

Miler Lagos's works investigate materiality and often incorporate reused or recycled materials, in part as a comment on diminishing natural resources. This work, which looks like a cross-section of a tree, is constructed from folded stock pages. It is from the artist's Tree Rings Dating series, which examines the relationship between business and nature, commodities and culture. He explains how the series began: "The idea came from the rings that become visible in a tree's trunk when it is cut. They not only reveal the tree's age, but also information about environmental conditions at different moments in time. The sheets of newspaper form concentric circles, evoking time in the same way as recorded in trees." Lagos prefers newspapers because, in his words, "the essence of the wood is still inside the paper. It's like the knowledge inside the tree...I was thinking about the nature of materials and how we use them to create our culture. I wasn’t thinking of it from an environmental position, but it became that."

ROSEMARY LAING

weather #10, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.5

Rosemary Laing originally trained as a painter in the late 1970s. She began working in the medium of photography in the late 1980s. Although she initially experimented with digital manipulation as a way to investigate how technologies can alter experiences of time and place, her more recent photographic work employs actual performers and installations. This work, from her series weather, considers human influence on the weather. In this staged photograph, a female performer is shown suspended and encircled by a whirlwind of shredded newspaper strips that largely obscure her. Swept up by hurricane-like forces—and surrounded by clippings of articles on climate change, the environment, and extreme weather—the figure at the center can be read as a casualty of inaction on climate change.

KEVIN COOLEY

Driggs, 2008

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.10

Kevin Cooley works with elemental forces of nature to question systems of knowledge as they relate to our perceptions and experience of everyday life, and to delve into our complex, evolving relationships to nature, to technology, and ultimately to each other. This photograph is from his series Light's Edge. Cooley writes: "Desolate views of American landscapes are illuminated by eerie distress signals, possibly messages coming from above or vice-versa. Lightning shooting through the sky highlights an endangered beauty and at the same time represents a divine or extraterrestrial phenomenon. This project was shot on location in the American states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—one of the most rugged and least populous regions of the country. Specific locations were primarily chosen for their majestic natural and scenic qualities, with an underlying element of historical significance as well. Many of the locations are important places for the local Native American tribes or are situated on, or near, the paths of early western explorers as well as pioneers—all of who[m] once struggled in this rugged landscape."

KEVIN COOLEY

Longyearbyen Overview, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2007.3

Kevin Cooley's photograph depicts the northernmost town on the planet, Longyearbyen, in Svalbard, Norway. Longyearbyen not only is a site where tourists flock to witness the northern lights each year, but also is on the front lines of climate change. Glaciers are melting and permafrost is thawing at an alarming rate there, and the town is seen by many as forewarning of what will eventually happen around the planet. Since 1970, average annual temperatures have risen by 4 degrees Celsius in Svalbard, with winter temperatures rising more than 7 degrees, according to a report released by the Norwegian Center for Climate Services in February 2019. A Climate in Svalbard 2100 report states that the annual mean air temperature in Svalbard is projected to increase by 7 to 10 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, and since 1979, the Arctic sea ice extent has declined by nearly 12 percent per decade.

ESTEBAN CABEZA DE BACA

Backbone of the Universe, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.7

Esteban Cabeza de Baca grew up in San Ysidro, California, on the border between the United States and Mexico. Cabeza de Baca—whose ancestry is Spanish, Mexican, Apache, and Zuni—describes his paintings and process: "Last time I was in New Mexico the idea of working in abstract circular planes came to me. The landscape is so vast there and thinking about my ancestors in the earth was inspiring. I was mesmerized by the expansiveness of the sky and wanted to connect with it in painting. Abstraction is my way to expand the grandeur and experience of nature. Sometimes painting in plein air and repeating what I see does an injustice to nature. The one way to unleash the spirit inside the red earth is to work emotionally. What does the earth feel like to touch? What does the smell of fresh icy mountain breeze taste like? Painting is my gateway to connect with nature on a deeper level."

KIM KEEVER

July 6, 2004

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2006.9

Kim Keever studied thermal engineering and spent a summer conducting research at NASA before he became an artist. He creates these large-scale photographs by constructing miniature topographies inside a 100-gallon aquarium. First, Keever fills the tank with water and adds pigments, next he lights the tank with colored gels, and then he uses a large-format camera to capture the ephemeral atmospheres on film. The result is a strange and beautiful image, one that initially seems to be a document of a real environment, but in the end is merely an artistic illusion. His works reference the history of landscape painting, the sublime, and dialogues on the relationship between art and nature. "Beauty is often considered a dirty word in the art world," the artist observes. "But some people get away with it, and hopefully I'm one of them."

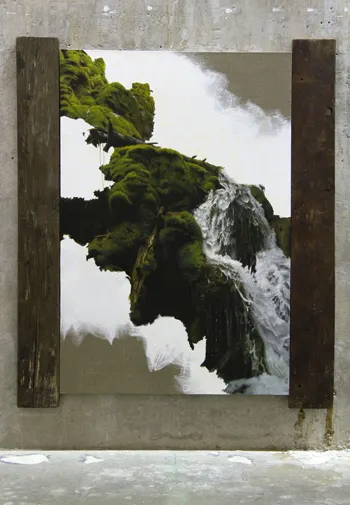

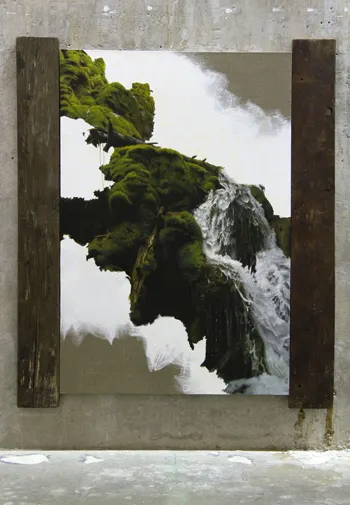

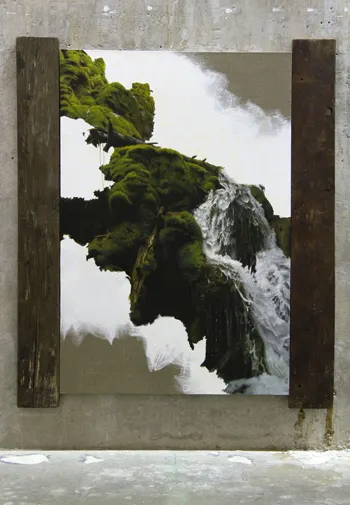

PAUL JACOBSEN

Seminary, 2011

Oil on linen and wood

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.1

Born in Denver, Paul Jacobsen grew up in a small mountain town in Colorado in a family of artists. Largely self-taught, Jacobsen works in traditional media such as oil and charcoal and his work investigates the intersection of nature and technology. As he has stated, "My painting acknowledges the romantic ideals of the power of nature, while at the same time celebrates the ways that art is a direct product of a domesticated, luxury society." Jacobsen currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

THOMAS KOVACHEVICH

Solid Geometry, 2014

Corrugated plastic

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2015.11

Formerly a physician, Thomas Kovachevich's minimalist sculptures explore the potential of unconventional materials, such as corrugated plastic. He describes this sculpture: "I named this work Solid Geometry, mostly because I like the way it sounds when it’s said aloud. It's poetic. Technically, solid geometry was the term used for the study of three-dimensional objects. Euclid created this system. But Euclidian solid geometry would be of no use if one were to mathematically define and describe this work. A far more complex geometry would be required. Solid Geometry was created not with mathematics in mind, but from an intuitive system. The incomprehensible is what intrigues. Something mysterious, primal and biological is at work." Kovachevich's more recent work expands his explorations in Solid Geometry. For example, in his 2019 exhibition Portrait of a Room, which was inspired by the water cycle that regulates life on the planet, some of the works change in relation to the climate of the space, as part of the artist's larger reconsideration of the history of modernism and his interest in ecological minimalism.

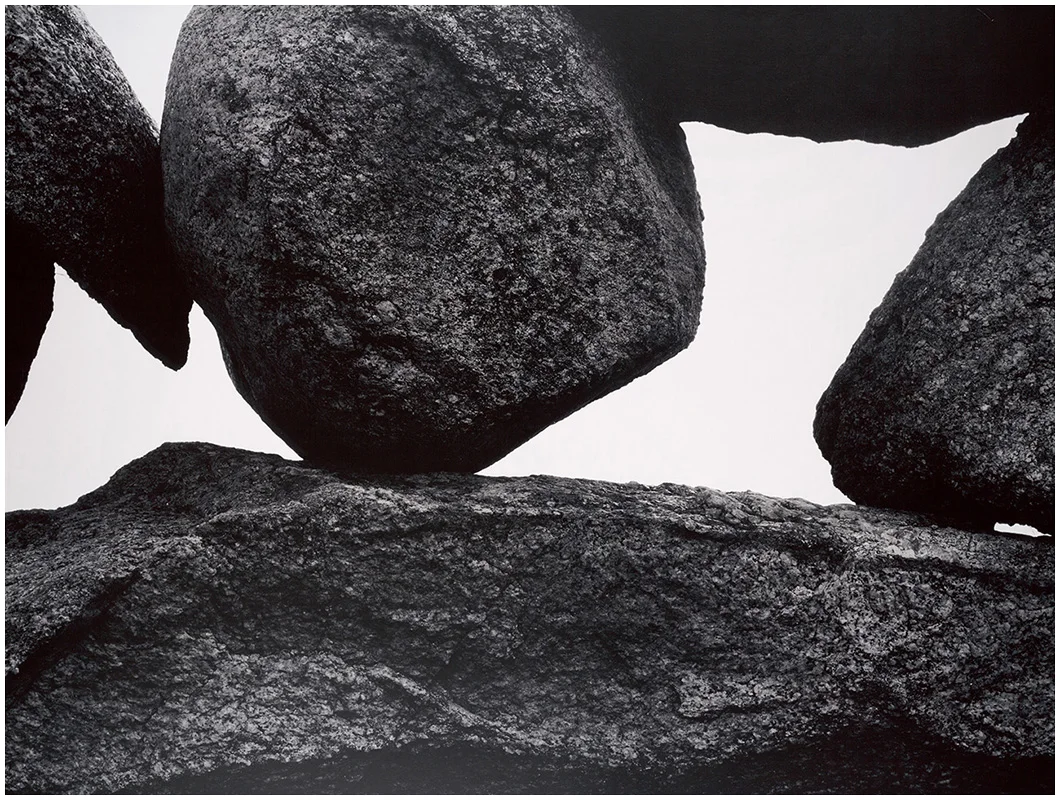

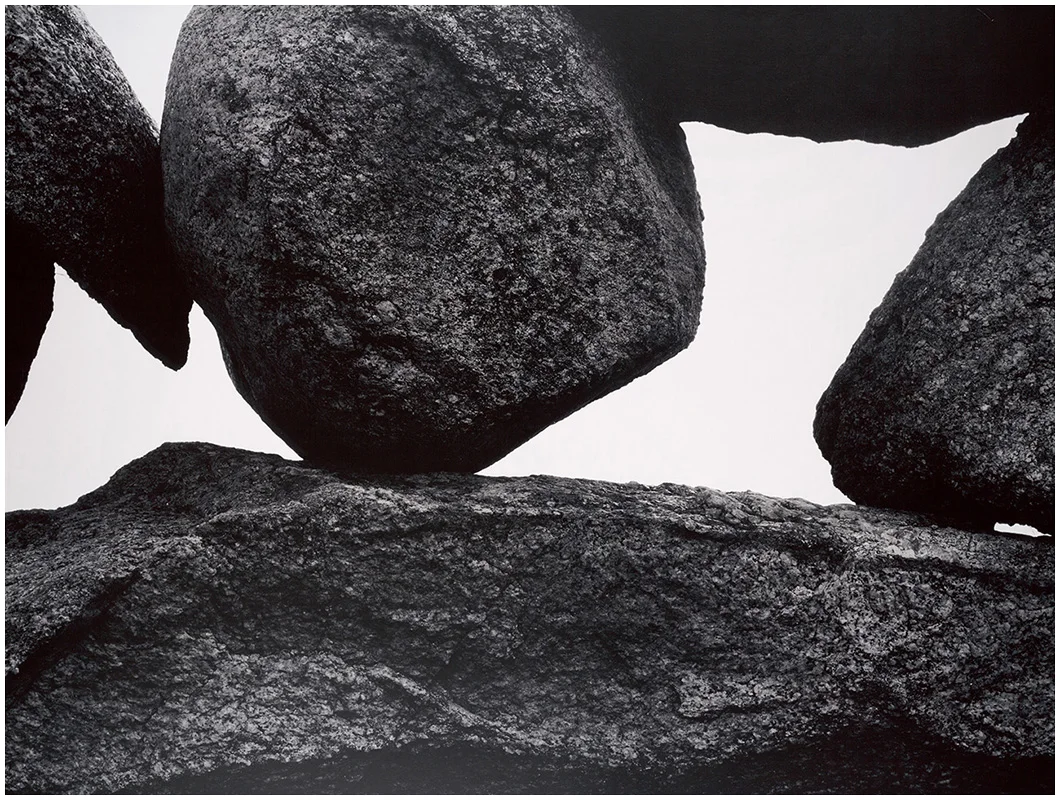

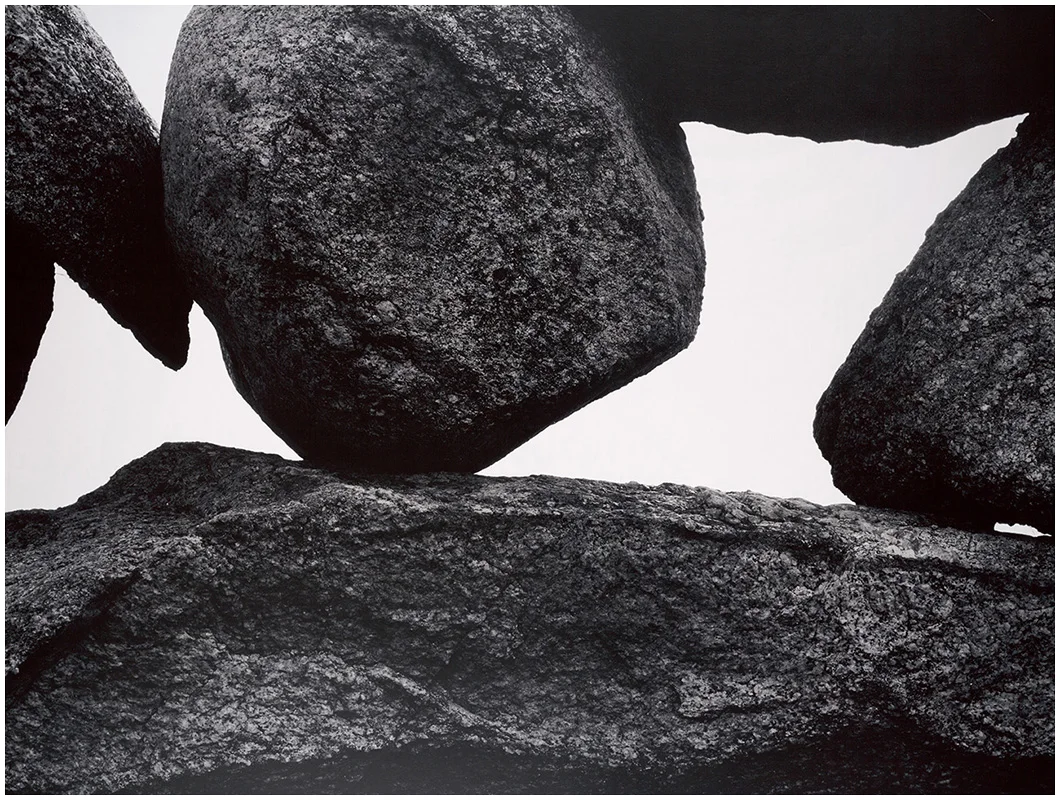

AARON SISKIND

Martha's Vineyard 107 B, 1954

Gelatin silver print mounted on aluminum

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1984.133

© 2020 Estate of Aaron Siskind

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Aaron Siskind was born in New York. He began his career in photography in 1932, working for the New York Film and Photo League on a range of documentary and social reform projects. In the 1940 she started searching for a new kind of image, and shifted toward abstraction. Siskind explained: "I found I wasn't saying anything. Special meaning was not in the pictures but in the subject. I began to feel that reality was something that existed only in our minds and feelings." He photographed a range of subjects in sharp detail, from rope strands and seaweed on the beaches in Gloucester, Massachusetts, to pictures of road tar painted over cracked and weathered asphalt. In the 1950s he began his series of majestic landscapes, depicting stacked boulders on Martha's Vineyard. These richly textured and nearly abstract compositions are both in dialogue with Abstract Expressionist paintings of the period and ruminations on the interrelationship of art, nature, and representation.

LOIS TARLOW

Untitled, 1985

Pastel on paper

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1985.30

"As far back atrs I can remember, I wanted to be an artist," Lois Tarlow recalls. "From age 4, I would spend many whole days drawing at the desk in the office of my father’s sole leather factory." Tarlow would go on to study with Karl Zerbe and Hyman Bloom at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and has been a significant figure in the New England art world for more than seven decades. Her work can be found in the collections of many local institutions, including the Rose Art Museum, the Harvard Art Museums, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tarlow works in many media, creating layered works on subjects ranging from psychology and hidden histories to major life events and landscapes. In this expressive pastel drawing of a forest, Tarlow shows the simultaneous fragility and strength of nature.

AGNIESZKA KURANT

Map of Phantom Islands, 2011

Pigment print on archival paper

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.6

Agnieszka Kurant's conceptual art centers on "the economy of the invisible," the ways in which immaterial and imaginary entities, fictions, and phantoms influence political and economic systems. As Kurant stated in a 2015 interview with Sabine Russ of BOMB Magazine, "The evolution of intelligence has always fascinated me. Culture and art seem to have emerged, just like religion, at some point of human evolution. Do they have an expiration date? Will they eventually evolve into another collective adaptation, conditioned by changing environment, climate, and technology?"

This work is from Kurant's The Phantom Islands series and is part of her ongoing examination of "phantom capital." These phantom islands or “phantom territories” have appeared on maps at different points in history. While some were observed as mirages, others were invented by explorers or governments, and, in some cases, even led to real conflict. Researching the origins of the individual islands from centuries-old cartographic archives, Kurant aggregates individual territories falsely claimed by imperial rulers and kingdoms onto a single map. Playing with ideas of illusion and truth, these maps look at how fictions and rumors shape our understanding of reality.

LORI NIX

Natural History, 2005

Chromogenic print mounted on sintra

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2005.16

Lori Nix and her partner Kathleen Gerber craft highly detailed, small-scale dioramas by hand, which Nix then photographs. This work, from the series Lost, was inspired by natural history displays of the 1940s and 1950s, particularly those at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Nix describes, "The walls are deteriorating, the ceilings are falling in, and the structures barely stand; yet Mother Nature is slowly taking them over. These spaces are filled with flora, fauna and insects, reclaiming what was theirs before man's encroachment. I am afraid of what the future holds if we do not change our ways regarding the climate, but at the same time I am fascinated by what a changing world can bring."

Nix and Gerber have also explored natural disasters in other series, such as in Circleville, from their series, Accidentally Kansas. Nix explains: 'My childhood was spent in a rural part of the United States that is known more for its natural disasters than anything else. I was born in a small town in western Kansas, and each passing season brought its own drama, from winter snowstorms, spring floods and tornados to summer insect infestations and drought. Whereas most adults viewed these seasonal disruptions with angst, for a child it was considered euphoric. Downed trees, mud, even grass fires brought excitement to daily, mundane life."

GARY CARSLEY

D.63 MacArthur Park, 2007

Lambda monoprint

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.3

Gary Carsley's work hybridizes traditional artistic media, such as painting, photography, and drawing, with digital and immersive technologies in order to engage with globalization and other contemporary political and cultural topics. He is particularly interested in the handmade as a way to resist uniformity. To make these "draguerreotypes," as he calls them, Carsley takes photographs of parks from around the world, such as this image of MacArthur Park in Los Angeles. Then, working with a vast archive of digital copies of woodgrain veneers purchased from hardware stores in different countries, he creates a collaged image of that place, fragment by fragment. While the resulting work may look like intarsia—the decorative wood process in which a design or pattern is made by assembling small pieces of veneer in various shapes—it is actually a photographic monoprint composed of digital copies, leaving the viewer to question what is "natural."

SARAH ANNE JOHNSON

Explosions, 2011

Chromogenic print and photospotting ink

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2013.7

In 2009, as part of an artist residency, Sarah Anne Johnson boarded a double-masted schooner and traveled in the Arctic Circle. "It was exotic, breathtakingly beautiful and sublime," Johnson recounts. "It seemed so pristine and perfect, vast and strong, but also somehow delicate and fleeting. After such an experience, one can't help speculating about the impact we have on this planet." Her experience led to a new series of work, Arctic Wonderland, and this reflection: "We are in the process of creating irreparable damage to the earth and will soon have no choice but to gamble on increasingly dubious theories. A favorite theory of engineers as a last resort to stop global warming is the blocking out of the sun. With this body of work I have been assessing and questioning western ideas of progress, growth and innovation. What are we progressing toward? Where does innovation lead us? How big can we go? What will it mean for us to take over the sun? Not only for the environment, but also psychologically for us, what will that mean?"

Johnson explored these concerns in the photographs she took during the expedition by variously painting, photoshopping, embossing, and printing on them "to create a more honest image. To show not just what I saw, but how I feel about what I saw." The artist's ink interventions, such as the addition of fireworks seen here, are meant to highlight the beauty of the landscape while also drawing attention to the way humans have altered it.

HENRY P. HUNT

Cutting Ice at Spy Pond, Arlington, Massachusetts, 1859

Oil on canvas

Gift of Frederic Tudor to the Business Historical Society, 1934

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1934.2

This painting by Henry P. Hunt depicts the Tudor Ice Company harvesting ice from Spy Pond in the town of Arlington, Massachusetts. Established by Frederic Tudor in Boston in 1806, prior to the age of refrigeration, the Tudor Ice Company transported ice by rail and ship from freshwater ponds to locations around the world, including India, Singapore, Jamaica, and Cuba. In the case, "The Ice King," Professor Tom Nicholas illustrates how Tudor pioneered a new industry, creating a global market for a natural resource once considered worthless, and became a key figure in the history of American entrepreneurship. Hunt's painting is an important document of Tudor's innovative industry, and can also be a model for 21st-century entrepreneurs investing in new technologies and experimenting with novel ways to use natural resources. The Tudor Company Records are held in Baker Library Special Collections.

DAN FORD

Melville and Hawthorne (American Poetry), 2000

Oil on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.18

Contemporary artist Dan Ford's painting is a witty play on Asher B. Durand's 1849 Kindred Spirits (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), which portrays the artist Thomas Cole and the poet and critic William Cullen Bryant in the Catskill Mountains. Here Ford reworks Durand’s iconic painting, substituting Cole and Bryant with the writers Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne in the foreground, and inserting a McDonald’s restaurant in the background as his comment on the changing American landscape and the "blizzards of convenience" that have "blanketed New England in malls and McDonald's" in his lifetime. Unlike Durand’s painting, where Cole and Bryant contemplate the kindred arts of painting and poetry while walking in nature, here, as Ford describes, "Melville and Hawthorne...go for a wander through the primordial forest and come upon the sublime vision: the Golden Archway!"

JAMES CASEBERE

Flooded Hallway, 1998–1999

Dye destruction print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2003.5

© 2020 James Casebere

James Casebere's photograph shows a hallway flooded with water. However, this is not a photograph of an actual flooded building, but rather of a table-top model the artist constructed that uses a special type of poured resin known as "E-2 Water" to create a simulation of a flooded space, which both challenges the idea of the photograph as a document and pushes the boundaries of the medium. Casebere began making these images in 1998. In an interview with fellow artist Roberto Juarez, he stated: "The first image where I did use water was...based on photographs of flooded bunkers under the Reichstag. The water as a metaphor is about the passage of time. It's about temporality. But it’s also about emotion, an excess of emotion...about some sense of fullness. Maybe it’s a fear of drowning. It's also a sense of overflow—good or bad—but movement." As Juarez noted in response, "Casebere's photographs evoke our deepest fears and longings' and also “captivate our collective imagination, the one ruled by instinct." Viewed in the context of climate change, rising seas, and extreme floods happening today around the world, Casebere's conceptual constructions can also take on new meaning.

MILER LAGOS

195 Rings, 2010

Newspaper collage

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2011.12

Miler Lagos's works investigate materiality and often incorporate reused or recycled materials, in part as a comment on diminishing natural resources. This work, which looks like a cross-section of a tree, is constructed from folded stock pages. It is from the artist's Tree Rings Dating series, which examines the relationship between business and nature, commodities and culture. He explains how the series began: "The idea came from the rings that become visible in a tree's trunk when it is cut. They not only reveal the tree's age, but also information about environmental conditions at different moments in time. The sheets of newspaper form concentric circles, evoking time in the same way as recorded in trees." Lagos prefers newspapers because, in his words, "the essence of the wood is still inside the paper. It's like the knowledge inside the tree...I was thinking about the nature of materials and how we use them to create our culture. I wasn’t thinking of it from an environmental position, but it became that."

ROSEMARY LAING

weather #10, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.5

Rosemary Laing originally trained as a painter in the late 1970s. She began working in the medium of photography in the late 1980s. Although she initially experimented with digital manipulation as a way to investigate how technologies can alter experiences of time and place, her more recent photographic work employs actual performers and installations. This work, from her series weather, considers human influence on the weather. In this staged photograph, a female performer is shown suspended and encircled by a whirlwind of shredded newspaper strips that largely obscure her. Swept up by hurricane-like forces—and surrounded by clippings of articles on climate change, the environment, and extreme weather—the figure at the center can be read as a casualty of inaction on climate change.

KEVIN COOLEY

Driggs, 2008

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.10

Kevin Cooley works with elemental forces of nature to question systems of knowledge as they relate to our perceptions and experience of everyday life, and to delve into our complex, evolving relationships to nature, to technology, and ultimately to each other. This photograph is from his series Light's Edge. Cooley writes: "Desolate views of American landscapes are illuminated by eerie distress signals, possibly messages coming from above or vice-versa. Lightning shooting through the sky highlights an endangered beauty and at the same time represents a divine or extraterrestrial phenomenon. This project was shot on location in the American states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—one of the most rugged and least populous regions of the country. Specific locations were primarily chosen for their majestic natural and scenic qualities, with an underlying element of historical significance as well. Many of the locations are important places for the local Native American tribes or are situated on, or near, the paths of early western explorers as well as pioneers—all of who[m] once struggled in this rugged landscape."

KEVIN COOLEY

Longyearbyen Overview, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2007.3

Kevin Cooley's photograph depicts the northernmost town on the planet, Longyearbyen, in Svalbard, Norway. Longyearbyen not only is a site where tourists flock to witness the northern lights each year, but also is on the front lines of climate change. Glaciers are melting and permafrost is thawing at an alarming rate there, and the town is seen by many as forewarning of what will eventually happen around the planet. Since 1970, average annual temperatures have risen by 4 degrees Celsius in Svalbard, with winter temperatures rising more than 7 degrees, according to a report released by the Norwegian Center for Climate Services in February 2019. A Climate in Svalbard 2100 report states that the annual mean air temperature in Svalbard is projected to increase by 7 to 10 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, and since 1979, the Arctic sea ice extent has declined by nearly 12 percent per decade.

ESTEBAN CABEZA DE BACA

Backbone of the Universe, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.7

Esteban Cabeza de Baca grew up in San Ysidro, California, on the border between the United States and Mexico. Cabeza de Baca—whose ancestry is Spanish, Mexican, Apache, and Zuni—describes his paintings and process: "Last time I was in New Mexico the idea of working in abstract circular planes came to me. The landscape is so vast there and thinking about my ancestors in the earth was inspiring. I was mesmerized by the expansiveness of the sky and wanted to connect with it in painting. Abstraction is my way to expand the grandeur and experience of nature. Sometimes painting in plein air and repeating what I see does an injustice to nature. The one way to unleash the spirit inside the red earth is to work emotionally. What does the earth feel like to touch? What does the smell of fresh icy mountain breeze taste like? Painting is my gateway to connect with nature on a deeper level."

KIM KEEVER

July 6, 2004

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2006.9

Kim Keever studied thermal engineering and spent a summer conducting research at NASA before he became an artist. He creates these large-scale photographs by constructing miniature topographies inside a 100-gallon aquarium. First, Keever fills the tank with water and adds pigments, next he lights the tank with colored gels, and then he uses a large-format camera to capture the ephemeral atmospheres on film. The result is a strange and beautiful image, one that initially seems to be a document of a real environment, but in the end is merely an artistic illusion. His works reference the history of landscape painting, the sublime, and dialogues on the relationship between art and nature. "Beauty is often considered a dirty word in the art world," the artist observes. "But some people get away with it, and hopefully I'm one of them."

PAUL JACOBSEN

Seminary, 2011

Oil on linen and wood

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.1

Born in Denver, Paul Jacobsen grew up in a small mountain town in Colorado in a family of artists. Largely self-taught, Jacobsen works in traditional media such as oil and charcoal and his work investigates the intersection of nature and technology. As he has stated, "My painting acknowledges the romantic ideals of the power of nature, while at the same time celebrates the ways that art is a direct product of a domesticated, luxury society." Jacobsen currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

THOMAS KOVACHEVICH

Solid Geometry, 2014

Corrugated plastic

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2015.11

Formerly a physician, Thomas Kovachevich's minimalist sculptures explore the potential of unconventional materials, such as corrugated plastic. He describes this sculpture: "I named this work Solid Geometry, mostly because I like the way it sounds when it’s said aloud. It's poetic. Technically, solid geometry was the term used for the study of three-dimensional objects. Euclid created this system. But Euclidian solid geometry would be of no use if one were to mathematically define and describe this work. A far more complex geometry would be required. Solid Geometry was created not with mathematics in mind, but from an intuitive system. The incomprehensible is what intrigues. Something mysterious, primal and biological is at work." Kovachevich's more recent work expands his explorations in Solid Geometry. For example, in his 2019 exhibition Portrait of a Room, which was inspired by the water cycle that regulates life on the planet, some of the works change in relation to the climate of the space, as part of the artist's larger reconsideration of the history of modernism and his interest in ecological minimalism.

AARON SISKIND

Martha's Vineyard 107 B, 1954

Gelatin silver print mounted on aluminum

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1984.133

© 2020 Estate of Aaron Siskind

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Aaron Siskind was born in New York. He began his career in photography in 1932, working for the New York Film and Photo League on a range of documentary and social reform projects. In the 1940 she started searching for a new kind of image, and shifted toward abstraction. Siskind explained: "I found I wasn't saying anything. Special meaning was not in the pictures but in the subject. I began to feel that reality was something that existed only in our minds and feelings." He photographed a range of subjects in sharp detail, from rope strands and seaweed on the beaches in Gloucester, Massachusetts, to pictures of road tar painted over cracked and weathered asphalt. In the 1950s he began his series of majestic landscapes, depicting stacked boulders on Martha's Vineyard. These richly textured and nearly abstract compositions are both in dialogue with Abstract Expressionist paintings of the period and ruminations on the interrelationship of art, nature, and representation.

LOIS TARLOW

Untitled, 1985

Pastel on paper

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1985.30

"As far back atrs I can remember, I wanted to be an artist," Lois Tarlow recalls. "From age 4, I would spend many whole days drawing at the desk in the office of my father’s sole leather factory." Tarlow would go on to study with Karl Zerbe and Hyman Bloom at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and has been a significant figure in the New England art world for more than seven decades. Her work can be found in the collections of many local institutions, including the Rose Art Museum, the Harvard Art Museums, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tarlow works in many media, creating layered works on subjects ranging from psychology and hidden histories to major life events and landscapes. In this expressive pastel drawing of a forest, Tarlow shows the simultaneous fragility and strength of nature.

AGNIESZKA KURANT

Map of Phantom Islands, 2011

Pigment print on archival paper

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.6

Agnieszka Kurant's conceptual art centers on "the economy of the invisible," the ways in which immaterial and imaginary entities, fictions, and phantoms influence political and economic systems. As Kurant stated in a 2015 interview with Sabine Russ of BOMB Magazine, "The evolution of intelligence has always fascinated me. Culture and art seem to have emerged, just like religion, at some point of human evolution. Do they have an expiration date? Will they eventually evolve into another collective adaptation, conditioned by changing environment, climate, and technology?"

This work is from Kurant's The Phantom Islands series and is part of her ongoing examination of "phantom capital." These phantom islands or “phantom territories” have appeared on maps at different points in history. While some were observed as mirages, others were invented by explorers or governments, and, in some cases, even led to real conflict. Researching the origins of the individual islands from centuries-old cartographic archives, Kurant aggregates individual territories falsely claimed by imperial rulers and kingdoms onto a single map. Playing with ideas of illusion and truth, these maps look at how fictions and rumors shape our understanding of reality.

LORI NIX

Natural History, 2005

Chromogenic print mounted on sintra

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2005.16

Lori Nix and her partner Kathleen Gerber craft highly detailed, small-scale dioramas by hand, which Nix then photographs. This work, from the series Lost, was inspired by natural history displays of the 1940s and 1950s, particularly those at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Nix describes, "The walls are deteriorating, the ceilings are falling in, and the structures barely stand; yet Mother Nature is slowly taking them over. These spaces are filled with flora, fauna and insects, reclaiming what was theirs before man's encroachment. I am afraid of what the future holds if we do not change our ways regarding the climate, but at the same time I am fascinated by what a changing world can bring."

Nix and Gerber have also explored natural disasters in other series, such as in Circleville, from their series, Accidentally Kansas. Nix explains: 'My childhood was spent in a rural part of the United States that is known more for its natural disasters than anything else. I was born in a small town in western Kansas, and each passing season brought its own drama, from winter snowstorms, spring floods and tornados to summer insect infestations and drought. Whereas most adults viewed these seasonal disruptions with angst, for a child it was considered euphoric. Downed trees, mud, even grass fires brought excitement to daily, mundane life."

GARY CARSLEY

D.63 MacArthur Park, 2007

Lambda monoprint

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.3

Gary Carsley's work hybridizes traditional artistic media, such as painting, photography, and drawing, with digital and immersive technologies in order to engage with globalization and other contemporary political and cultural topics. He is particularly interested in the handmade as a way to resist uniformity. To make these "draguerreotypes," as he calls them, Carsley takes photographs of parks from around the world, such as this image of MacArthur Park in Los Angeles. Then, working with a vast archive of digital copies of woodgrain veneers purchased from hardware stores in different countries, he creates a collaged image of that place, fragment by fragment. While the resulting work may look like intarsia—the decorative wood process in which a design or pattern is made by assembling small pieces of veneer in various shapes—it is actually a photographic monoprint composed of digital copies, leaving the viewer to question what is "natural."

SARAH ANNE JOHNSON

Explosions, 2011

Chromogenic print and photospotting ink

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2013.7

In 2009, as part of an artist residency, Sarah Anne Johnson boarded a double-masted schooner and traveled in the Arctic Circle. "It was exotic, breathtakingly beautiful and sublime," Johnson recounts. "It seemed so pristine and perfect, vast and strong, but also somehow delicate and fleeting. After such an experience, one can't help speculating about the impact we have on this planet." Her experience led to a new series of work, Arctic Wonderland, and this reflection: "We are in the process of creating irreparable damage to the earth and will soon have no choice but to gamble on increasingly dubious theories. A favorite theory of engineers as a last resort to stop global warming is the blocking out of the sun. With this body of work I have been assessing and questioning western ideas of progress, growth and innovation. What are we progressing toward? Where does innovation lead us? How big can we go? What will it mean for us to take over the sun? Not only for the environment, but also psychologically for us, what will that mean?"

Johnson explored these concerns in the photographs she took during the expedition by variously painting, photoshopping, embossing, and printing on them "to create a more honest image. To show not just what I saw, but how I feel about what I saw." The artist's ink interventions, such as the addition of fireworks seen here, are meant to highlight the beauty of the landscape while also drawing attention to the way humans have altered it.

STEPHEN MALLON

The Reefing of USS Radford, 2012

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.15

This photograph, from Stephen Mallon's solo exhibition The Reefing of USS Radford, is part of the artist's American Reclamation series, which chronicles and examines the American recycling industry, in this case a Spruance-class destroyer in the United States Navy re-purposed to create an artificial reef. The USS Arthur W. Radford (DD-968) was named for Admiral Arthur W. Radford USN (1896–1973). It was decommissioned on March 18, 2003, after 26 years in service, and on August 10, 2011, became part of the DelJersey Land Reef through the Delaware Reef Program, which aims to help depleted or endangered fisheries. Mallon explains: "My American Reclamation series chronicles the beauty of industrial recycling in the United States. In 2010, the USS Radford, a former Naval Spruance destroyer became the longest vessel to be reefed in the Atlantic Ocean. Its final mission serves to create a habitat for marine life and a discovery site for divers."

DAN FORD

Melville and Hawthorne (American Poetry), 2000

Oil on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2001.18

Contemporary artist Dan Ford's painting is a witty play on Asher B. Durand's 1849 Kindred Spirits (Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art), which portrays the artist Thomas Cole and the poet and critic William Cullen Bryant in the Catskill Mountains. Here Ford reworks Durand’s iconic painting, substituting Cole and Bryant with the writers Herman Melville and Nathaniel Hawthorne in the foreground, and inserting a McDonald’s restaurant in the background as his comment on the changing American landscape and the "blizzards of convenience" that have "blanketed New England in malls and McDonald's" in his lifetime. Unlike Durand’s painting, where Cole and Bryant contemplate the kindred arts of painting and poetry while walking in nature, here, as Ford describes, "Melville and Hawthorne...go for a wander through the primordial forest and come upon the sublime vision: the Golden Archway!"

JAMES CASEBERE

Flooded Hallway, 1998–1999

Dye destruction print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2003.5

© 2020 James Casebere

James Casebere's photograph shows a hallway flooded with water. However, this is not a photograph of an actual flooded building, but rather of a table-top model the artist constructed that uses a special type of poured resin known as "E-2 Water" to create a simulation of a flooded space, which both challenges the idea of the photograph as a document and pushes the boundaries of the medium. Casebere began making these images in 1998. In an interview with fellow artist Roberto Juarez, he stated: "The first image where I did use water was...based on photographs of flooded bunkers under the Reichstag. The water as a metaphor is about the passage of time. It's about temporality. But it’s also about emotion, an excess of emotion...about some sense of fullness. Maybe it’s a fear of drowning. It's also a sense of overflow—good or bad—but movement." As Juarez noted in response, "Casebere's photographs evoke our deepest fears and longings' and also “captivate our collective imagination, the one ruled by instinct." Viewed in the context of climate change, rising seas, and extreme floods happening today around the world, Casebere's conceptual constructions can also take on new meaning.

MILER LAGOS

195 Rings, 2010

Newspaper collage

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2011.12

Miler Lagos's works investigate materiality and often incorporate reused or recycled materials, in part as a comment on diminishing natural resources. This work, which looks like a cross-section of a tree, is constructed from folded stock pages. It is from the artist's Tree Rings Dating series, which examines the relationship between business and nature, commodities and culture. He explains how the series began: "The idea came from the rings that become visible in a tree's trunk when it is cut. They not only reveal the tree's age, but also information about environmental conditions at different moments in time. The sheets of newspaper form concentric circles, evoking time in the same way as recorded in trees." Lagos prefers newspapers because, in his words, "the essence of the wood is still inside the paper. It's like the knowledge inside the tree...I was thinking about the nature of materials and how we use them to create our culture. I wasn’t thinking of it from an environmental position, but it became that."

ROSEMARY LAING

weather #10, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.5

Rosemary Laing originally trained as a painter in the late 1970s. She began working in the medium of photography in the late 1980s. Although she initially experimented with digital manipulation as a way to investigate how technologies can alter experiences of time and place, her more recent photographic work employs actual performers and installations. This work, from her series weather, considers human influence on the weather. In this staged photograph, a female performer is shown suspended and encircled by a whirlwind of shredded newspaper strips that largely obscure her. Swept up by hurricane-like forces—and surrounded by clippings of articles on climate change, the environment, and extreme weather—the figure at the center can be read as a casualty of inaction on climate change.

KEVIN COOLEY

Driggs, 2008

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.10

Kevin Cooley works with elemental forces of nature to question systems of knowledge as they relate to our perceptions and experience of everyday life, and to delve into our complex, evolving relationships to nature, to technology, and ultimately to each other. This photograph is from his series Light's Edge. Cooley writes: "Desolate views of American landscapes are illuminated by eerie distress signals, possibly messages coming from above or vice-versa. Lightning shooting through the sky highlights an endangered beauty and at the same time represents a divine or extraterrestrial phenomenon. This project was shot on location in the American states of Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming—one of the most rugged and least populous regions of the country. Specific locations were primarily chosen for their majestic natural and scenic qualities, with an underlying element of historical significance as well. Many of the locations are important places for the local Native American tribes or are situated on, or near, the paths of early western explorers as well as pioneers—all of who[m] once struggled in this rugged landscape."

KEVIN COOLEY

Longyearbyen Overview, 2006

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2007.3

Kevin Cooley's photograph depicts the northernmost town on the planet, Longyearbyen, in Svalbard, Norway. Longyearbyen not only is a site where tourists flock to witness the northern lights each year, but also is on the front lines of climate change. Glaciers are melting and permafrost is thawing at an alarming rate there, and the town is seen by many as forewarning of what will eventually happen around the planet. Since 1970, average annual temperatures have risen by 4 degrees Celsius in Svalbard, with winter temperatures rising more than 7 degrees, according to a report released by the Norwegian Center for Climate Services in February 2019. A Climate in Svalbard 2100 report states that the annual mean air temperature in Svalbard is projected to increase by 7 to 10 degrees Celsius by the end of this century, and since 1979, the Arctic sea ice extent has declined by nearly 12 percent per decade.

ESTEBAN CABEZA DE BACA

Backbone of the Universe, 2019

Acrylic on canvas

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.7

Esteban Cabeza de Baca grew up in San Ysidro, California, on the border between the United States and Mexico. Cabeza de Baca—whose ancestry is Spanish, Mexican, Apache, and Zuni—describes his paintings and process: "Last time I was in New Mexico the idea of working in abstract circular planes came to me. The landscape is so vast there and thinking about my ancestors in the earth was inspiring. I was mesmerized by the expansiveness of the sky and wanted to connect with it in painting. Abstraction is my way to expand the grandeur and experience of nature. Sometimes painting in plein air and repeating what I see does an injustice to nature. The one way to unleash the spirit inside the red earth is to work emotionally. What does the earth feel like to touch? What does the smell of fresh icy mountain breeze taste like? Painting is my gateway to connect with nature on a deeper level."

KIM KEEVER

July 6, 2004

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2006.9

Kim Keever studied thermal engineering and spent a summer conducting research at NASA before he became an artist. He creates these large-scale photographs by constructing miniature topographies inside a 100-gallon aquarium. First, Keever fills the tank with water and adds pigments, next he lights the tank with colored gels, and then he uses a large-format camera to capture the ephemeral atmospheres on film. The result is a strange and beautiful image, one that initially seems to be a document of a real environment, but in the end is merely an artistic illusion. His works reference the history of landscape painting, the sublime, and dialogues on the relationship between art and nature. "Beauty is often considered a dirty word in the art world," the artist observes. "But some people get away with it, and hopefully I'm one of them."

PAUL JACOBSEN

Seminary, 2011

Oil on linen and wood

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.1

Born in Denver, Paul Jacobsen grew up in a small mountain town in Colorado in a family of artists. Largely self-taught, Jacobsen works in traditional media such as oil and charcoal and his work investigates the intersection of nature and technology. As he has stated, "My painting acknowledges the romantic ideals of the power of nature, while at the same time celebrates the ways that art is a direct product of a domesticated, luxury society." Jacobsen currently lives and works in Brooklyn, New York.

THOMAS KOVACHEVICH

Solid Geometry, 2014

Corrugated plastic

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2015.11

Formerly a physician, Thomas Kovachevich's minimalist sculptures explore the potential of unconventional materials, such as corrugated plastic. He describes this sculpture: "I named this work Solid Geometry, mostly because I like the way it sounds when it’s said aloud. It's poetic. Technically, solid geometry was the term used for the study of three-dimensional objects. Euclid created this system. But Euclidian solid geometry would be of no use if one were to mathematically define and describe this work. A far more complex geometry would be required. Solid Geometry was created not with mathematics in mind, but from an intuitive system. The incomprehensible is what intrigues. Something mysterious, primal and biological is at work." Kovachevich's more recent work expands his explorations in Solid Geometry. For example, in his 2019 exhibition Portrait of a Room, which was inspired by the water cycle that regulates life on the planet, some of the works change in relation to the climate of the space, as part of the artist's larger reconsideration of the history of modernism and his interest in ecological minimalism.

AARON SISKIND

Martha's Vineyard 107 B, 1954

Gelatin silver print mounted on aluminum

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1984.133

© 2020 Estate of Aaron Siskind

The son of Russian Jewish immigrants, Aaron Siskind was born in New York. He began his career in photography in 1932, working for the New York Film and Photo League on a range of documentary and social reform projects. In the 1940 she started searching for a new kind of image, and shifted toward abstraction. Siskind explained: "I found I wasn't saying anything. Special meaning was not in the pictures but in the subject. I began to feel that reality was something that existed only in our minds and feelings." He photographed a range of subjects in sharp detail, from rope strands and seaweed on the beaches in Gloucester, Massachusetts, to pictures of road tar painted over cracked and weathered asphalt. In the 1950s he began his series of majestic landscapes, depicting stacked boulders on Martha's Vineyard. These richly textured and nearly abstract compositions are both in dialogue with Abstract Expressionist paintings of the period and ruminations on the interrelationship of art, nature, and representation.

LOIS TARLOW

Untitled, 1985

Pastel on paper

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1985.30

"As far back atrs I can remember, I wanted to be an artist," Lois Tarlow recalls. "From age 4, I would spend many whole days drawing at the desk in the office of my father’s sole leather factory." Tarlow would go on to study with Karl Zerbe and Hyman Bloom at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, and has been a significant figure in the New England art world for more than seven decades. Her work can be found in the collections of many local institutions, including the Rose Art Museum, the Harvard Art Museums, the deCordova Sculpture Park and Museum, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Tarlow works in many media, creating layered works on subjects ranging from psychology and hidden histories to major life events and landscapes. In this expressive pastel drawing of a forest, Tarlow shows the simultaneous fragility and strength of nature.

AGNIESZKA KURANT

Map of Phantom Islands, 2011

Pigment print on archival paper

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2019.6

Agnieszka Kurant's conceptual art centers on "the economy of the invisible," the ways in which immaterial and imaginary entities, fictions, and phantoms influence political and economic systems. As Kurant stated in a 2015 interview with Sabine Russ of BOMB Magazine, "The evolution of intelligence has always fascinated me. Culture and art seem to have emerged, just like religion, at some point of human evolution. Do they have an expiration date? Will they eventually evolve into another collective adaptation, conditioned by changing environment, climate, and technology?"

This work is from Kurant's The Phantom Islands series and is part of her ongoing examination of "phantom capital." These phantom islands or “phantom territories” have appeared on maps at different points in history. While some were observed as mirages, others were invented by explorers or governments, and, in some cases, even led to real conflict. Researching the origins of the individual islands from centuries-old cartographic archives, Kurant aggregates individual territories falsely claimed by imperial rulers and kingdoms onto a single map. Playing with ideas of illusion and truth, these maps look at how fictions and rumors shape our understanding of reality.

LORI NIX

Natural History, 2005

Chromogenic print mounted on sintra

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2005.16

Lori Nix and her partner Kathleen Gerber craft highly detailed, small-scale dioramas by hand, which Nix then photographs. This work, from the series Lost, was inspired by natural history displays of the 1940s and 1950s, particularly those at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Nix describes, "The walls are deteriorating, the ceilings are falling in, and the structures barely stand; yet Mother Nature is slowly taking them over. These spaces are filled with flora, fauna and insects, reclaiming what was theirs before man's encroachment. I am afraid of what the future holds if we do not change our ways regarding the climate, but at the same time I am fascinated by what a changing world can bring."

Nix and Gerber have also explored natural disasters in other series, such as in Circleville, from their series, Accidentally Kansas. Nix explains: 'My childhood was spent in a rural part of the United States that is known more for its natural disasters than anything else. I was born in a small town in western Kansas, and each passing season brought its own drama, from winter snowstorms, spring floods and tornados to summer insect infestations and drought. Whereas most adults viewed these seasonal disruptions with angst, for a child it was considered euphoric. Downed trees, mud, even grass fires brought excitement to daily, mundane life."

GARY CARSLEY

D.63 MacArthur Park, 2007

Lambda monoprint

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2008.3

Gary Carsley's work hybridizes traditional artistic media, such as painting, photography, and drawing, with digital and immersive technologies in order to engage with globalization and other contemporary political and cultural topics. He is particularly interested in the handmade as a way to resist uniformity. To make these "draguerreotypes," as he calls them, Carsley takes photographs of parks from around the world, such as this image of MacArthur Park in Los Angeles. Then, working with a vast archive of digital copies of woodgrain veneers purchased from hardware stores in different countries, he creates a collaged image of that place, fragment by fragment. While the resulting work may look like intarsia—the decorative wood process in which a design or pattern is made by assembling small pieces of veneer in various shapes—it is actually a photographic monoprint composed of digital copies, leaving the viewer to question what is "natural."

SARAH ANNE JOHNSON

Explosions, 2011

Chromogenic print and photospotting ink

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2013.7

In 2009, as part of an artist residency, Sarah Anne Johnson boarded a double-masted schooner and traveled in the Arctic Circle. "It was exotic, breathtakingly beautiful and sublime," Johnson recounts. "It seemed so pristine and perfect, vast and strong, but also somehow delicate and fleeting. After such an experience, one can't help speculating about the impact we have on this planet." Her experience led to a new series of work, Arctic Wonderland, and this reflection: "We are in the process of creating irreparable damage to the earth and will soon have no choice but to gamble on increasingly dubious theories. A favorite theory of engineers as a last resort to stop global warming is the blocking out of the sun. With this body of work I have been assessing and questioning western ideas of progress, growth and innovation. What are we progressing toward? Where does innovation lead us? How big can we go? What will it mean for us to take over the sun? Not only for the environment, but also psychologically for us, what will that mean?"

Johnson explored these concerns in the photographs she took during the expedition by variously painting, photoshopping, embossing, and printing on them "to create a more honest image. To show not just what I saw, but how I feel about what I saw." The artist's ink interventions, such as the addition of fireworks seen here, are meant to highlight the beauty of the landscape while also drawing attention to the way humans have altered it.

STEPHEN MALLON

The Reefing of USS Radford, 2012

Chromogenic print

Schwartz Art Collection, Harvard Business School, 2012.15

This photograph, from Stephen Mallon's solo exhibition The Reefing of USS Radford, is part of the artist's American Reclamation series, which chronicles and examines the American recycling industry, in this case a Spruance-class destroyer in the United States Navy re-purposed to create an artificial reef. The USS Arthur W. Radford (DD-968) was named for Admiral Arthur W. Radford USN (1896–1973). It was decommissioned on March 18, 2003, after 26 years in service, and on August 10, 2011, became part of the DelJersey Land Reef through the Delaware Reef Program, which aims to help depleted or endangered fisheries. Mallon explains: "My American Reclamation series chronicles the beauty of industrial recycling in the United States. In 2010, the USS Radford, a former Naval Spruance destroyer became the longest vessel to be reefed in the Atlantic Ocean. Its final mission serves to create a habitat for marine life and a discovery site for divers."

HENRY P. HUNT

Cutting Ice at Spy Pond, Arlington, Massachusetts, 1859

Oil on canvas

Gift of Frederic Tudor to the Business Historical Society, 1934

HBS Art and Artifacts Collection, 1934.2

This painting by Henry P. Hunt depicts the Tudor Ice Company harvesting ice from Spy Pond in the town of Arlington, Massachusetts. Established by Frederic Tudor in Boston in 1806, prior to the age of refrigeration, the Tudor Ice Company transported ice by rail and ship from freshwater ponds to locations around the world, including India, Singapore, Jamaica, and Cuba. In the case, "The Ice King," Professor Tom Nicholas illustrates how Tudor pioneered a new industry, creating a global market for a natural resource once considered worthless, and became a key figure in the history of American entrepreneurship. Hunt's painting is an important document of Tudor's innovative industry, and can also be a model for 21st-century entrepreneurs investing in new technologies and experimenting with novel ways to use natural resources. The Tudor Company Records are held in Baker Library Special Collections.

These collections are available for use in the de Gaspé Beaubien Reading Room.

Our team is here to help.