Breaking Down the Barriers

As photography became more firmly established as the medium of choice for print advertising, the boundaries between fine art and commercial photography began to break down. The Art Directors Club (ADC) was founded in 1920 to address the tension between advertising art and fine art with the goal “to dignify the field of business art in the eyes of artists” and put forward the notion that “artistic excellence is vitally necessary to successful advertising.”14 Heyworth Campbell, ADC’s first president and art director of Vogue, noted in 1924, “Art is not a thing to be done, but the best way of doing that which is necessary to be done. This brings a tobacco advertisement into the realm of art as truly as the designing of a cathedral.”15

Edward Steichen, a highly regarded photographic artist, also championed this trend. “Stieglitz worked hard to establish photography as a truly modern art,” Michele Bogart writes. “Steichen was of a different generation and sensibility. He could build upon the aesthetic and institutional foundation Stieglitz helped to create, but was always more at home in the worlds of commerce and consumption.”16 Recognizing his reputation as an extraordinary portraitist and the prestige his name could lend to commercial work, the J. Walter Thompson Advertising Agency hired Steichen in 1923, the same year he became chief photographer for Condé Nast Publications.

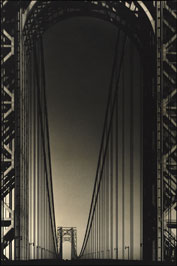

Steichen and his contemporaries, many of whose works were shown in the NAAI exhibition, deftly traversed the worlds of high art, fashion, and commerce.17 A number of artists in the exhibition came from major metropolitan centers in the United States and also from Europe, where avant-garde elements of Cubism and Surrealism were incorporated into photography in the 1920s and ’30s. Using raking light, dramatic shadows, and oblique angles, photographers like Gilbert Seehausen and Alfredo Valente created striking portraits to illustrate editorial content, fashion spreads, and advertisements alike. Advertisers recognized the value a modernist photographic sensibility could bring to their products. As Margaret Watkins, one of many photographers who shifted from a soft focus, pictorialist style to a modernist one, explained, “With Cézanne, Matisse, Picasso came a new approach. . . . The comprehending photographer, saw, paused, and seized his camera. . . . [T]he eye of the advertiser was alert.”18

Several photographers featured at Rockefeller Plaza—including Anton Bruehl, Margaret Bourke-White, and Ralph Steiner—were students of Clarence White. Like Steichen, White developed an appreciation of photography’s artistic as well as its commercial applications. He was a founding president of the Pictorial Photographers of America and in 1914 established the Clarence H. White School of Photography in New York City, where he left his mark as a highly influential teacher.

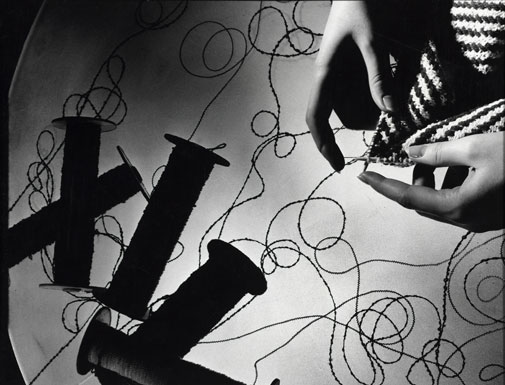

White’s students experimented with design, composition, and lighting, and in the early 1920s a number of their works in Vanity Fair included modernist views of everyday objects.19 “[White] provided a bridge between the older amateur of the photographic societies and a younger generation of professionally oriented art photographers,” Bonnie Yochelson notes in Pictorialism into Modernism: The Clarence White School of Photography (Rizzoli, 1996). “White collaborated with art directors, publishers, and graphic designers who, like him, were seeking to define the artist’s role in the communications revolution of the 1920s.”20

- http://www.adcglobal.org/adc/history/

- Heyworth Campbell, Art Center Bulletin 1, no. 1 (September 1924): 14, in Marianne Fulton, ed., text by Bonnie Yochelson, Kathleen Erwin, Pictorialism into Modernism: The Clarence H. White School of Photography. New York: Rizzoli, 1996, p. 92.

- Bogart, note 6, p. 179. Steichen pursuit of commercial work earned him criticism as well. See Patricia Johnston, Real Fantasies: Edward Steichen’s Advertising Photography. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997, pp. 219–222.

- The NAAI exhibition included 5 prints by Steichen. These images were not among those that came to the Harvard Business School in 1935.

- “Advertising and Photography,” Pictorial Photography in America 4 (1926).

- A modernist sensibility was emerging in product design itself. The Exposition International des Arts Décoratifs et Industriel Modernes in Paris in 1925 showcased Art Deco styles in contemporary design; the following year the Metropolitan Museum of Art sponsored a traveling show of pieces it had included in the Paris exposition.

- Bonnie Yochelson, “Clarence H. White: Peaceful Warrior,” in Fulton, Yochelson, and Erwin, note 14, p. 12.