1873: Off the Rails

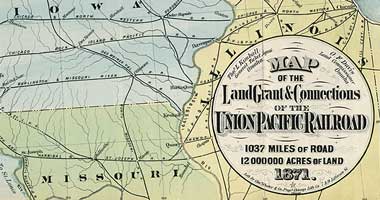

The Panic of 1873 originated in the rapid expansion of the American securities market in response to the capital demands of the war effort and railway development. Many small investors got their first taste of the securities market while buying bonds floated to finance the U. S. Civil War. When the war was over, railroad entrepreneurs found a ready market for stocks and bonds to fund the massive expansion that culminated in the Union Pacific Railroad’s completion of the first transcontinental route in 1869. But two years later, allegations of graft linking Congress and the Union Pacific’s funding arm, the Crédit Mobilier, weakened confidence in railroad financing.

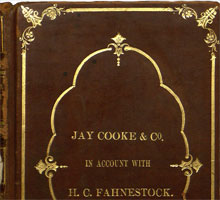

The trigger for the Panic of 1873 was the failure of Jay Cooke & Co., America’s premier banking house. Cooke made his name as the chief financier of the Union army, but he was a latecomer to railroad finance. By the time he agreed to fund the Northern Pacific Railway’s project to connect the Oregon coast with the existing northeastern rail network, the first transcontinental line had already been completed. Fears of overcapacity, along with cost overruns and the general distrust of railroad securities after the Crédit Mobilier scandal, depressed Northern Pacific bond prices in 1873. Cooke’s firm closed its doors in September, precipitating bank runs, a U.S. stock market panic, and (some argue) a worldwide depression that some scholars believe extended into the 1890s.7

Experts disagree on the underlying causes of the Panic of 1873, but most emphasize the ebb and flow of investment from Europe. Jay Cooke, for example, was one of many American bankers who established a London house in the 1860s as part of a broader effort to secure European funds. Cooke’s difficulties in 1873 were compounded by the U.S. Treasury’s decision to force him to share the profits of floating a government loan with a syndicate that included major European bankers such as the House of Rothschild and Barings Brothers—not to mention Cooke’s main American rival, the German-educated J. P. Morgan.8

German investors played a particularly large role in financing American railroads—and in instigating the panic. The German appetite for American railroad securities increased in the mid-1860s after the United States emerged from civil war, and indemnity payments from France after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871) further swelled the German capital available for overseas investment. However, demand contracted suddenly in 1873. Liberalization of the German economy meant increased availability of investment opportunities closer to home, made still more attractive in comparison to the scandal-ridden American railroads. Finally, the bursting of a real estate bubble in the capitals of Central Europe led to a banking panic in May 1873. American financiers, like Cooke, who had made plans in the expectation of European funds, were hard-pressed to stay solvent when those funds failed to materialize.9

- Henrietta Larson, Jay Cooke, Private Banker (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1936), pp. 254–279, 383–411.↖

- Ibid., pp. 182–183, 309, 393–399.↖

- For two very different analyses that both emphasize connections between the U.S. and the German economies, see Charles P. Kindleberger, Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, 5th ed. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2005), p. 137; and Peter Mixon, “The Crisis of 1873: Perspectives from Multiple Asset Classes,” Journal of Economic History 68, no. 3 (2008): 722–757.↖