- Introduction

- EDUCATION

- INNOVATION & VC

- GLOBAL LEGACY

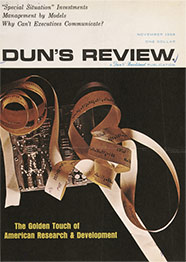

I n 1960, ARD invested $3.6 million in 18 companies and, by 1961, the firm became the first venture capital firm with shares listed on the New York Stock Exchange. In the article "Scientific Risk-Taking Keeps Paying Off for American Research & Development," Barron's described Doriot as a "gentle, soft-spoken man [who] seems ill-suited to the title "General" except that he goes about investing American Research money with a sort of idealistic fervor, as though directing a crusade."51 Doriot explained the success of ARD in these terms: "Technology has proved a rewarding field for American Research and is particularly well suited for creative capital investment. . . . In specialized technical areas with products protected by patents and know-how, it is easier for small companies to compete with large organizations."52

Throughout the 1960s, the firm continued to invest in innovative startups. ARD portfolio companies included Textron Electronics (aerospace, industrial, and metal products); Cordis Corporation (therapeutic medical equipment including angiography injectors, catheters, and pacemakers); and Transitron (semiconductors). ARD's success inspired New England's high-tech boom and the spread of companies that began to populate Route 128 surrounding Boston and Cambridge. A number of ARD employees also went on to start their own venture capital firms: William Elfers (HBS MBA '43) and Charles P. Waite (HBS MBA '59) founded Greylock Capital; James F. Morgan (HBS MBA '64) established Flagship Ventures (formerly Morgan, Holland Ventures); and William H. Congleton (HBS MBA '48) and John A. Shane (HBS MBA '60) founded The Palmer Organization.

"If I were a speculator, the question of return would apply. But I don't consider a speculator—in my definition of the word—constructive. I am building men and companies."

Georges F. Doriot, in "General Doriot"s Dream Factory," Fortune, August 1967 50

Doriot also championed a global community of venture capitalists by promoting venture capital organizations internationally. In 1961, with an investment of $5 million from Canadian financial institutions, Doriot helped establish the Canadian Enterprise Development Corporation (CED), one of Canada's first venture capital firms. The European Enterprise Development Company (EED) was formally incorporated in 1963 with support from shareholders in the US as well as European banks and financial institutions. John A. Shane explained, "[Doriot] felt that venture capital was not a uniquely American phenomenon. He felt the same kind of stimulus could work in other places."53 Like ARD, CED and EED invested in innovative technologies.

By the 1970s, the seeds of change for ARD were in the air. The Small Business Investment Act of 1953 had promoted the creation of small business investment corporations (SBICs) through financial support and loans. Over time, the financial benefits offered by SBICs created competition with ARD and other venture capital firms.54 In addition, ARD was formed as a closed-end investment fund regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), which placed limits on how those working for ARD could be compensated. Employees, for example, were not allowed to have stock options in firms in which ARD invested. At this time, Doriot also observed the increasingly speculative, profit-motivated nature of the field noting, "Venture capital seems to have shifted from a constructive, difficult task to a new method of speculation." 55

A possible solution to the growing competition from other venture capital firms and SEC regulations soon emerged. In 1972, Textron submitted a merger proposal, and ARD accepted. Two years later Doriot stepped down from active management of ARD but remained a member of its board of directors. 56 "[Doriot] was the creator of the concept of formalizing the startup and nurturing of businesses as a business—to feed capital to entrepreneurs to foster rapid growth for our society and the new firm's products for consumers," investment analyst and author Kenneth L. Fisher asserts. "It was his formula for success, and today's standard formula for breathing life into new industries and industry as a whole." 57

50

Doriot quoted in Gene Bylinsky, "General Doriot's Dream Factory," Fortune, August 1967: 104.

51

David A. Loehwing, Barron's, 26 September 1960: 3.

52 Doriot, "Creative Capital," speech delivered March 9, 1961 quoted in Ante, 172.

53

John A. Shane quoted in Ante, 181.

54

See Nicholas and Chen, 10; see also Ante, 160.

55

Doriot, ARD Annual Report, 1971, 4.

56

In 1985 Textron sold some of its divisions and made ARD into a limited private partnership.

57 Doriot quoted in Kenneth L. Fisher, 100 Minds that Made the Market (Woodside, Calif.: Business Classics, 2007), 148.