About the Exhibit

- Investigating Disruptive Technology

- New England Textile Industry

- Cotton Spinning Machinery

- Emergence of Ring Spinning

- Challenging the Industry Standard

Investigating Disruptive Technology

Investigating Disruptive TechnologyThe concept of disruptive technologies, first developed by Harvard Business School professors Richard S. Rosenbloom, Joseph L. Bower, and Clayton M. Christensen, cuts across many industry types and time periods. A disruptive technology is a new product or innovation that sneaks into an established market because industry leaders fail to recognize the threat it poses. Since not all new technologies will be disruptive technologies, they are not always easy to recognize. However, disruptive technologies that damage an established company typically have three important characteristics: they initially underperform established products, they present new benefits that enable new applications for new customers, and their performance characteristically improves rapidly. The irony is that companies do not succumb to disruptive technologies because of a lack of foresight, management savvy, or knowledge of the market. Rather, they underestimate the role that the new technology may play in emerging future markets and choose to focus on developing the sustaining technologies that their customers want today. Sailing ship companies, steam locomotive builders, and disk drive manufacturers are just a few of the many industries that have failed to see that apparently marginal and inferior technologies can cost them their entire business.

Although introduced between 1828 and 1835, ring spinning was not embraced by the leading textile producers of New England and the machine builders who supplied them until the 1850s. This may be an early illustration of the thesis that leading companies often fail to catch the wave of new, disruptive technologies. Using the rich primary and secondary resources of the Baker Library, this exhibition will investigate the emergence of ring spinning and how to gather the evidence needed to decide whether it qualifies as an early example of disruptive technology.

Although introduced between 1828 and 1835, ring spinning was not embraced by the leading textile producers of New England and the machine builders who supplied them until the 1850s. This may be an early illustration of the thesis that leading companies often fail to catch the wave of new, disruptive technologies. Using the rich primary and secondary resources of the Baker Library, this exhibition will investigate the emergence of ring spinning and how to gather the evidence needed to decide whether it qualifies as an early example of disruptive technology.

New England Textile Industry

The textile industry in New England, particularly in the second half of the nineteenth century, was engaged in a large-scale experiment that would eventually set the standard in the United States for industrialization in general and textile manufacture in specific. The integrated textile mills became the prototype for establishing factories nationwide as they determined the most effective plans for factory layout, development and maintenance of machinery, management of labor, and utilization of regional resources. One of the most significant developments in the industry during this period involved the integration of all the cloth production processes into one mill. While steps like spinning and weaving might have been carried out previously by separate producers, the integrated mills were designed to handle textile production from raw fiber to completed bolts of cloth. The size, scale, and productivity of the integrated New England textile mills and the machine shops that supported and supplied them had an impact on almost every area of development in the textile industry, including innovations in machinery.

Cotton Spinning Machinery

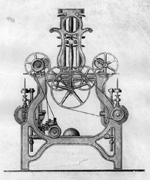

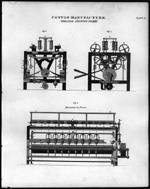

The process of spinning, or drawing out and twisting cotton fibers into yarn that can then be used for knitting or weaving, is a key component of cotton manufacture. Textile factory automation was pioneered in England in the last few decades of the eighteenth century, led by the cotton spinning inventions of Richard Arkwright and Samuel Crompton. Arkwright's flyer frame and Crompton's mule quickly became the industry standards of British cotton manufacture. This technology was introduced to the United States in 1790 when Samuel Slater emigrated to Rhode Island. Slater teamed up with the firm of Almy and Brown, successfully combining his knowledge of the manufacturing processes with the firm's capital and market, and set the stage for the growth of cotton manufacture in New England. The spinning machinery used in the Slater mills was a version of Arkwright's flyer frame and became a standard in the growing numbers of American cotton mills. The mule, so-called because it was a hybrid of Hargreaves' spinning jenny and Arkwright's flyer frame, was also widely used in the United States, particularly for spinning finer yarns. The flyer frame and the mule represent the well-established industry standards with which the ring spinning frame was to compete.

Emergence of Ring Spinning

American mills and machine shops took the lead in the development of cotton spinning machinery following the success of the Slater ventures in Rhode Island. In 1828 John Thorp patented an American alternative to the flyer and the mule, known as ring spinning, but it took nearly twenty years of development and experimentation before his invention emerged as a strong competitor. There is evidence in early manuscript records that machine shops were experimenting with ring frames and components in the 1830s. The success of the ring frame, however, was dependent on the market it served and it was not until industry leaders like Whitin Machine Works in the 1840s and the Lowell Machine Shop in the 1850s began to manufacture ring frames that the technology started to take hold. Primary resources like the manuscript order books, shop inventories, ledgers, patent negotiations and agreements, contracts, and correspondence, as well as the trade catalogs and advertising materials of textile manufacturers held here at the Baker Library all provide essential technical and historical data documenting the emergence of ring spinning.

Challenging the Industry Standard

The ring frame and the flyer frame are both examples of continuous spinners, which spun yarn and wound it onto bobbins in one motion, while the mule is a discontinuous spinner, first spinning a length of yarn and then winding that length onto bobbins separately. Despite attempts to develop all of these technologies, ring spinning had entirely displaced the flyer frame soon after the Civil War and had done the same to mule spinning by the early twentieth century. Comparative evaluations of the competing forms of cotton spinning machinery begin to appear in technical treatises on cotton manufacturing by at least 1840 and surface with increasing frequency after 1850. Historical accounts of spinning technology appear in both biographies of significant industrialists and histories of manufacturing firms. Technological development was largely dependent on companies strategizing their role in the textile market. Industry competition can be reconstructed with the help of federal manufacturing censuses in the nineteenth century, American business directories, and credit reports like those compiled in the manuscript ledgers of R.G. Dun & Company. The Baker Library's collections include resources of all these types, providing the tools needed to trace both the development in sustaining technology as well as the emergence of the potential disruptive technology.

Exhibit Directory | Selected Bibliography | Web Resources | Contact Information

Other Exhibits | Historical Collections | Baker Library Home